In the literature I’ve been teaching recently, I’ve been struck by how many fetish objects there are. Fetishes are things which, while insignificant in themselves, take on an outsized significance for someone. Often the significance is sexual although not necessarily. In today’s post I share ten fetish objects in literature that stand out.

Although an entire person can function as a fetish object–think Lolita or the Pygmalion-created Galatea–I’ve focused on small objects and body parts. Incidentally, I can think of at least one famous literary fetish that matches the original meaning of the word, which is to say an object believed to be inhabited by spirits or to have magical powers. I am thinking of the pig’s head in Lord of the Flies.

–A Girdle

While Sir Gawain resists all the other inducements that the Green Knight’s lady tries to seduce him with, he does accept her green girdle after she tells him it will save his life. Taking it shows that he cares more deeply for his life than he admits, and he turns bright red when he is caught wearing it. Afterwards, he carries it around as a badge of his shame, and the other Camelot knights don ribbons in a show of solidarity and humility.

–A Handkerchief

Iago, of course, uses the handkerchief that Othello gave Desdemona to goad the jealous Moor into murder. Here Othello calls upon Desdemona to yield it up:

Othello: I have a salt and sorry rheum offends me;

Lend me thy handkerchief.

Desdemona: Here, my lord.

Othello: That which I gave you.

Desdemona: I have it not about me.

Othello: Not?

Desdemona: No, indeed, my lord.

Othello: That is a fault.

That handkerchief

Did an Egyptian to my mother give;

She was a charmer, and could almost read

The thoughts of people: she told her, while she kept it,

‘Twould make her amiable and subdue my father

Entirely to her love, but if she lost it

Or made gift of it, my father’s eye

Should hold her loathed and his spirits should hunt

After new fancies: she, dying, gave it me;

And bid me, when my fate would have me wive,

To give it her. I did so: and take heed on’t;

Make it a darling like your precious eye;

To lose’t or give’t away were such perdition

As nothing else could match.

Desdemona: Is’t possible?

Othello: ‘Tis true: there’s magic in the web of it:

A sibyl, that had number’d in the world

The sun to course two hundred compasses,

In her prophetic fury sew’d the work;

The worms were hallow’d that did breed the silk;

And it was dyed in mummy which the skilful

Conserved of maidens’ hearts.

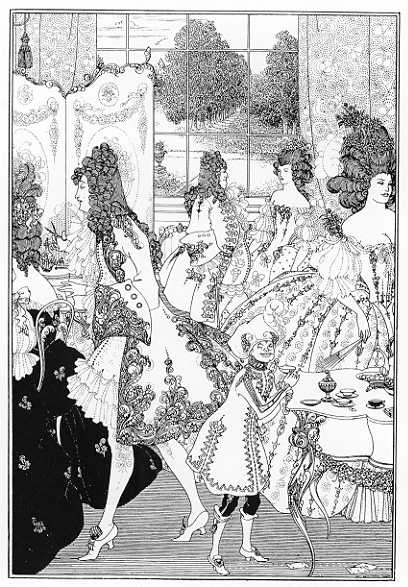

–A China Vase

Sexual innuendo flies wild and free in Wycherley’s infamous china scene. Caught visiting her lover by her husband in The Country Wife, Lady Jasper Fidget pretends that she is there to inspect some china. Thereafter, china takes on such ribald connotations that, for years after seeing the play, many spectators felt that they could not use the word “china” in polite society. Here’s Lady Fidget fending off Squeamish, a jealous rival, who wants to get some “china” of her own:

Enter Lady Fidget with a piece of China in her hand, and Horner following.

Lady Fidget: And I have been toyling and moyling, for the pretti’st piece of China, my Dear.

Horner: Nay she has been too hard for me do what I cou’d.

Squeamish: Oh Lord I’le have some China too, good Mr. Horner, don’t think to give other people China, and me none, come in with me too.

Horner: Upon my honor I have none left now.

Squeamish: Nay, nay I have known you deny your China before now, but you shan’t put me off so, come—

Horner: This Lady had the last there.

Lady Fidget: Yes indeed Madam, to my certain knowledge he has no more left.

Squeamish: O but it may be he may have some you could not find.

Lady Fidget: What d’y think if he had had any left, I would not have had it too, for we women of quality never think we have China enough.

–A Lock of Hair

Here’s how Pope describes one of literature’s great fetish objects:

This Nymph, to the Destruction of Mankind,

Nourish’d two Locks, which graceful hung behind

In equal Curls, and well conspir’d to deck

With shining Ringlets her smooth Iv’ry Neck.

Love in these Labyrinths his Slaves detains,

And mighty Hearts are held in slender Chains.

With hairy Sprindges we the Birds betray,

Slight Lines of Hair surprize the Finny Prey,

Fair Tresses Man’s Imperial Race insnare,

And Beauty draws us with a single Hair.

And here’s one of those insnared:

Th’ Adventrous Baron the bright Locks admir’d,

He saw, he wish’d, and to the Prize aspir’d:

Resolv’d to win, he meditates the way,

By Force to ravish, or by Fraud betray;

For when Success a Lover’s Toil attends,

Few ask, if Fraud or Force attain’d his Ends.

–A Muff

Sophia’s hand warmer is what sends Tom Jones into raptures. Once again, if you pick up any sexual innuendoes in the following passage, it’s the author’s intention:

And, to be sure, I could tell your ladyship something, but that I am afraid it would offend you.”—”What could you tell me, Honour?” says Sophia. “Nay, ma’am, to be sure he meant nothing by it, therefore I would not have your ladyship be offended.”—”Prithee tell me,” says Sophia; “I will know it this instant.”—”Why, ma’am,” answered Mrs Honour, “he came into the room one day last week when I was at work, and there lay your ladyship’s muff on a chair, and to be sure he put his hands into it; that very muff your ladyship gave me but yesterday. La! says I, Mr Jones, you will stretch my lady’s muff, and spoil it: but he still kept his hands in it: and then he kissed it—to be sure I hardly ever saw such a kiss in my life as he gave it.”—”I suppose he did not know it was mine,” replied Sophia. “Your ladyship shall hear, ma’am. He kissed it again and again, and said it was the prettiest muff in the world.

—A Band-aid and a Pencil Stub

–Emma’s gazes in fascinated horror as her protégé decides to rid herself of her memories of Mr. Elton:

She held the parcel towards her, and Emma read the words Most precious treasures on the top. Her curiosity was greatly excited. Harriet unfolded the parcel, and she looked on with impatience. Within abundance of silver paper was a pretty little Tunbridge-ware box, which Harriet opened: it was well lined with the softest cotton; but, excepting the cotton, Emma saw only a small piece of court-plaister.

“Now,” said Harriet, “you must recollect.”

“No, indeed I do not.”

“Dear me! I should not have thought it possible you could forget what passed in this very room about court-plaister, one of the very last times we ever met in it!—It was but a very few days before I had my sore throat—just before Mr. and Mrs. John Knightley came—I think the very evening.—Do not you remember his cutting his finger with your new penknife, and your recommending court-plaister?—But, as you had none about you, and knew I had, you desired me to supply him; and so I took mine out and cut him a piece; but it was a great deal too large, and he cut it smaller, and kept playing some time with what was left, before he gave it back to me. And so then, in my nonsense, I could not help making a treasure of it—so I put it by never to be used, and looked at it now and then as a great treat.”

And further on:

“Here,” resumed Harriet, turning to her box again, “here is something still more valuable, I mean that has been more valuable, because this is what did really once belong to him, which the court-plaister never did.”

Emma was quite eager to see this superior treasure. It was the end of an old pencil,—the part without any lead.

“This was really his,” said Harriet.—”Do not you remember one morning?—no, I dare say you do not. But one morning—I forget exactly the day—but perhaps it was the Tuesday or Wednesday before that evening, he wanted to make a memorandum in his pocket-book; it was about spruce-beer. Mr. Knightley had been telling him something about brewing spruce-beer, and he wanted to put it down; but when he took out his pencil, there was so little lead that he soon cut it all away, and it would not do, so you lent him another, and this was left upon the table as good for nothing. But I kept my eye on it; and, as soon as I dared, caught it up, and never parted with it again from that moment.”

–An Eye

For Poe, a human eye sometimes becomes something more than an eye:

It is impossible to say how first the idea entered my brain; but once conceived, it haunted me day and night. Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire. I think it was his eye! yes, it was this! He had the eye of a vulture –a pale blue eye, with a film over it. Whenever it fell upon me, my blood ran cold; and so by degrees –very gradually –I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye forever.

–A Cake

The most prominent object was a long table with a tablecloth spread on it, as if a feast had been in preparation when the house and the clocks all stopped together. An epergne or centre-piece of some kind was in the middle of this cloth; it was so heavily overhung with cobwebs that its form was quite undistinguishable; and, as I looked along the yellow expanse out of which I remember its seeming to grow, like a black fungus, I saw speckle-legged spiders with blotchy bodies running home to it, and running out from it, as if some circumstances of the greatest public importance had just transpired in the spider community.

I heard the mice too, rattling behind the panels, as if the same occurrence were important to their interests. But the black beetles took no notice of the agitation, and groped about the hearth in a ponderous elderly way, as if they were short-sighted and hard of hearing, and not on terms with one another.

These crawling things had fascinated my attention, and I was watching them from a distance, when Miss Havisham laid a hand upon my shoulder. In her other hand she had a crutch-headed stick on which she leaned, and she looked like the Witch of the place.

“This,” said she, pointing to the long table with her stick, “is where I will be laid when I am dead. They shall come and look at me here.”

With some vague misgiving that she might get upon the table then and there and die at once, the complete realization of the ghastly waxwork at the Fair, I shrank under her touch.

“What do you think that is?” she asked me, again pointing with her stick; “that, where those cobwebs are?”

“I can’t guess what it is, ma’am.”

“It’s a great cake. A bride-cake. Mine!”

–Another Cake

This one, far more appetizing, helps trigger one of literature’s greatest explorations:

No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory – this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me it was me. … Whence did it come? What did it mean? How could I seize and apprehend it? … And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before mass), when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom, my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it. And all from my cup of tea.

–A Hair

And finally, turning to a contemporary work, Salman Rushdie’s remarkable short story “The Prophet’s Hair” shows the chaos that occurs when a holy relic shows up in people’s lives, leaving miracles and an urge to be pure in its wake. The story is a brilliant satire of fundamentalists. Here’s one consequence described in the story:

But before our story can properly be concluded, it is necessary to record that when the four sons of the dead Sheikh awoke on the morning of his death, having unwittingly spent a few minutes under the same roof as the famous hair, they found that a miracle had occurred, that they were all sound of limb and storng of wind, as whole as they might have been if their father had not thought to smash their legs in the first hours of their lives. They were, all four of them, very properly furious, because the miracle had reduced their earning power by 75 percent, at the most conservative estimate, so they were ruined men.

Please send in your own examples.

One Trackback

[…] muff in Tom Jones and with Harriet’s obsession with Mr. Elton’s pencil stub in Emma. (See Thursday’s post on fetish objects.) These fixations struck them as incomprehensible desires from a bygone […]