Thursday

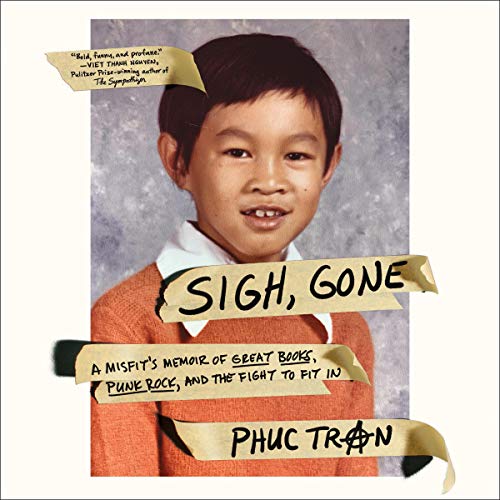

Sue Schmidt, friend and occasional contributor to this blog, has alerted me to a Vietnamese immigrant’s story of how the classics came to his aid as he wrestled with the challenges of cultural transition. Phuc Tran recounts his encounters with racism at school and violence at home in Sigh, Gone: A Misfit’s Memoir of Great Books, Punk Rock, and the Fight to Fit In (2020).

I’m only in the early stages of the book but what I’ve read so far is riveting. Tran’s family escaped Vietnam after the fall of Saigon—a story that has suddenly become relevant again with the Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan—and to stop the bullying in school, he concluded that he needed to be “less Asian.” Therefore, he “tried to erase my otherness, my Asianness, with an assimilation—an Americanization—that was relentless as it was thorough.”

One of the tools he chanced upon was Clifton Fadiman’s The Lifetime Reading Plan. As Tran describes it, Fadiman had “listed and summarized all the books that he thought educated, cultured Americans should read over their lifetime, beginning with the Bible and ending with Solzhenitsyn.” As Tran describes it, his introduction “was unapologetically American, classist, and white—and I loved it. The Plan would be the most powerful cannon in my war for assimilation.” The list of authors included Flaubert, Twain, Kerouac, Bronte, Kafka, Camus, Ibsen, James, Thurber, Shakespeare.

But something funny happened on the way to assimilation:

My reading molded me, the tool hammering its hand into shape. By some miracle—and by miracle, I mean great teachers—I pushed past the shallowness and stupidity of my own motivations. I fell in love with the actual literature and the actual ideas of great literature. As an immigrant, as a Vietnamese kid, as a poor kid, I had collected so many scarlet letters of alienation that I connected profoundly to the great works.

Tran elaborates:

As I read, I began to understand that all the great works wrangled with big questions, important questions: our place in the world, the value of our experience, the fairness and meaning of our suffering, our quest for love and belonging. Universal themes bound these great works together, and they bound me to their oaky, yellowed pages like Odysseus lashed to the mast of his ship. I felt a connective and humanizing resonance in books: I wasn’t alone in my aloneness. I wasn’t alone in my longing for love. I wasn’t alone in my fear of being rejected, my fear of never finding my place, my fear of failing. The snarl of my journey was untangled and laid out clearly by books.

And further:

In the great classics, there were so many moments for me to divest my age, my town, my skin, so many moments to be part of a universal conversation. Homer sharpened my mind’s edge. Dickinson gave me winged hope. Thoreau made a whole cabin for me.

To cite a couple of examples, Dostoevsky gave Tran a framework for the violence he encountered at home, triggered by his father’s PTSD and the stress everyone felt at being strangers in a strange land. Trans explains the power of the work as follows:

Violence lashed Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment to my childhood. The violence of Dostoevsky’s world is woven throughout Crime and Punishment, stitched into the very language of the novel’s narrative. In his tale about a desperate college student who murders two helpless women Dostoevsky plunges his reader into a paranoid world where violence hangs thick in the air. The violence and assault of his raw imagery, feverish and unyielding, is indelible. This was a world I knew from experience, a world I had grown up in, a world where violence was potentially everywhere.

The Scarlet Letter, meanwhile, provided its own complex framework. Originally thinking that Hester is a fool for accepting her punishment instead of leaving the colony, Tran comes to see her as consenting to be publicly shamed

because it’s where she has a powerful (albeit negative) identity, and from that robust identity comes her purpose and meaning. Hester chooses to stay where she is Hester.

Tran, meanwhile, came to accept a community that was calling him a gook. He allowed himself to be harmed by the word because, if he did, he

was showing them that I belonged at least by virtue of understanding their language. And all I wanted was to belong.

I’m early in the book and will report more as I get further into it. You can already see, however, the rich resource that literature provided him.