Tuesday

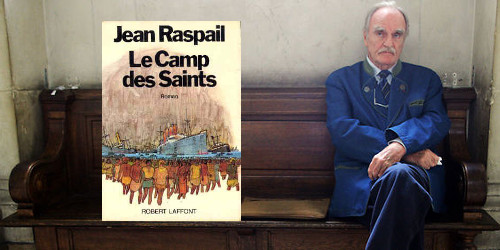

Move over, Atlas Shrugged. Welcome, Camp of Saints.

On second thought, you’re both welcome in GOP-controlled Washington.

If you need confirmation of the power of novels, you need look no further than how Ayn Rand guides House Speaker Paul Ryan and how Jean Raspail does the same for Senior Advisor to the President Steve Bannon.

I’ve written a lot about Ayn Rand but I’m just now hearing about the French novelist Raspail. Last month The Huffington Post had an in-depth article on his 1973 work, and Adam Gopnik of The New Yorker recently traced its roots in French fascism. It’s scary stuff.

The plot, laid out in Huffington Post, involves waves of immigrants overwhelming Europe and then America while the liberal multicultural left dithers around. Among the horrors that ensue are the following:

The French government eventually gives the order to repel the armada by force, but by then the military has lost the will to fight. Troops battle among themselves as the Indians stream on shore, trampling to death the left-wing radicals who came to welcome them. Poor black and brown people literally overrun Western civilization. Chinese people pour into Russia; the queen of England is forced to marry her son to a Pakistani woman; the mayor of New York must house an African-American family at Gracie Mansion. Raspail’s rogue heroes, the defenders of white Christian supremacy, attempt to defend their civilization with guns blazing but are killed in the process.

Last week I compared the sadomasochistic fantasies of German Freikorps soldiers to the budget priorities of Donald Trump. I need not have looked for such an indirect connection since Camp of Saints, openly praised by Trump’s senior advisor, has similar fantasies.

For instance, I mentioned how the enemy in those 1920s pulp novels is compared to a watery, oozing mass that threatens to inundate the hard, clear outlines of white German identity. The novels also see this mass as sexual—which is to say, brown skinned people represent a forbidden longing which rightwing readers have repressed. One already sees some of that sexuality in the above description of Camp of Saints, with its royal prince marrying a Pakistani and an African-American family residing at Gracie Mansion (horrors!). The forced race mixing of sexualized brown bodies with victimized white bodies haunts the nightmare fantasies of white supremacists.

The novel has even more vivid images elsewhere. As you read the following description of the novel, remember that it was written in 1973, when hippies would have been associated with the sexual revolution:

Only white Europeans like [protagonist] Calgues are portrayed as truly human in The Camp of the Saints. The Indian armada brings “thousands of wretched creatures” whose very bodies arouse disgust: “Scraggy branches, brown and black … All bare, those fleshless Gandhi-arms.” Poor brown children are spoiled fruit “starting to rot, all wormy inside, or turned so you can’t see the mold.”

The ship’s inhabitants are also sexual deviants who turn the voyage into a grotesque orgy. “Everywhere, rivers of sperm,” Raspail writes. “Streaming over bodies, oozing between breasts, and buttocks, and thighs, and lips, and fingers.”

The white Christian world is on the brink of destruction, the novel suggests, because these black and brown people are more fertile and more numerous, while the West has lost that necessary belief in its own cultural and racial superiority. As he talks to the hippie he will soon kill, Calgues explains how the youth went so wrong: “That scorn of a people for other races, the knowledge that one’s own is best, the triumphant joy at feeling oneself to be part of humanity’s finest — none of that had ever filled these youngsters’ addled brains.”

And now check out the relationship of the novel to the seven-nation Muslim ban enacted by the Trump administration. Huffington Post authors Paul Blumenthal and J. M. Rieger find several Steve Bannon Camp of Saints references in 2015 and 2016 that point to the origins of the ban:

“It’s been almost a Camp of the Saints-type invasion into Central and then Western and Northern Europe,” he said in October 2015.

“The whole thing in Europe is all about immigration,” he said in January 2016. “It’s a global issue today — this kind of global Camp of the Saints.”

“It’s not a migration,” he said later that January. “It’s really an invasion. I call it the Camp of the Saints.”

“When we first started talking about this a year ago,” he said in April 2016, “we called it the Camp of the Saints. … I mean, this is Camp of the Saints, isn’t it?”

Like the Friekorps fantasies described by Klaus Theweleit, there is a mixture of sadism and self-pitying masochism in Camp of Saints. On the one hand, Calgues gets to kill hippies. On the other hand, the good guys tragically but heroically are overwhelmed by the brown hoards at the end. Rightwing readers are able to shed cathartic tears for themselves in a self-pity party at how liberal policies victimize them.

The Freikorps fantasies are obviously junk, but Gopnik is worried about Camp of Saints. That’s because it comes out of a rightwing intellectual French tradition, which gives it a bit more respectability. As Gopnik observes,

Camp of Saints is not clumsily constructed hate literature in the way that the hideous anti-Semitic propaganda of the Nazi period and Julius Streicher is. It is instead designed as nostalgic literature mourning the passing of a coherent cultural structure that has been worn away from within.

This helps point to the explanation as to why the French right wing possesses, if not credibility, then at least surprising influence at home and abroad. In plain English, the French extreme right turned not to volk mythology but to royalism and the Roman Catholic Church, both of which were, at least to the eye of ideological desire, more passably attractive as counter-dreams to pluralistic liberalism than the fantasy creations of Germany or the United States. The French far right was aesthetic before it was, or as much as it was, authoritarian.

Gopnik cites the following passage from Raspail’s novel as an example:

While the old man sat there, eating and drinking, savoring swallow after swallow, he set his eyes wandering over the spacious room. A time-consuming task, since his glance stopped to linger on everything it touched, and since every confrontation was a new act of love. Now and then his eyes would fill with tears, but they were tears of joy. Each object in this house proclaimed the dignity of those who had lived here—their discretion, their propriety, their reserve, their taste for those solid traditions that one generation can pass on to the next, so long as it still takes pride in itself. And the old man’s soul was in everything, too. In the fine old bindings, the rustic benches, the Virgin carved in wood, the big cane chairs, the hexagonal tiles, the beams in the ceiling, the ivory crucifix with its sprig of dried box wood, and a hundred other things as well . . .

Raspail turns to old things, Gopnik points out, when he wants to elevate his reactionary longings. They stand in for what was once good and wholesome and pure.

Gopnik mentions that one of Raspail’s literary forebearers is Louis-Ferdinand Céline, a Nazi-sympathizing author whose Voyage to the End of the Night I read in a college 20th century French novels class. Céline’s novel is filled with such passages as,

I crawled back into myself all alone, just delighted to observe that I was even more miserable than before, because I had brought a new kind of distress and something that resembled true feeling into my solitude.

As I see it, the longing for a heroic past often arises out of a certain self loathing, with people looking for some cleansing savior to redeem them. As Gopnik points out, there can be a rightwing Catholic dimension to this dynamic–an obsession with human sin and corruption–and he finds traces of it in respected authors Léon Daudet, Paul Morand, G. K Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, all of them anti-Semitic.

Gopnik sums up Raspail’s current popularity amongst white nationalists as follows:

But the vogue of Raspail on the American extreme right…suggests that its apocalyptic aestheticism is simply the slightly more highbrow version of Donald Trump’s own more vulgar fantasies, the ones where American carnage and Celebrity Apprentice intertwine with grotesque intensity. Indeed, there’s a passage in Raspail’s novel, soon after the quotation above, where we’re brought into a ravaged New York where Central Park is occupied by bands of barbarians and a few terrified white people cling to its margins, an absurd image that exactly corresponds to Trump’s crazy image of American cities.

If you need a reminder that a multicultural democracy is not a rotting mass, turn to Walt Whitman’s multitudes, the crew of Melville’s Pequod, and all the rich immigrant novels that have been pumping new life into America for over two centuries. Think of Willa Cather, Anzia Yezierska, Ole Edvart Rolvaag, Bernard Malamud, Paule Marshall, Amy Tan, Maxine Hong Kingston, Sandra Cisneros, Bahrati Mukergee, Jamaica Kincaid, Julia Alvarez, Frank McCourt, Jeffrey Eugenides, Abraham Verghese, and Khaled Hosseini, to name just a few. Against that rich tapestry, complaints of our American Raspails seem like thin soup.

Not that this keeps them from whining. Huffington Post quotes one of the American publishers responsible for Camp of Saints:

“Over the years the American public has absorbed a great number of books, articles, poems and films which exalt the immigrant experience,” Tanton wrote in 1994. “It is easy for the feelings evoked by Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty to obscure the fact that we are currently receiving too many immigrants (and receiving them too fast) for the health of our environment and of our common culture. Raspail evokes different feelings and that may help to pave the way for policy changes.”

Bannon likes to talk about culture wars and a clash of civilizations. He claims he has Islam in mind, but “Islam” somehow extends to include Hispanics, African Americans, Jews, and multiculturalism generally. He’s right about the clash of civilizations, however. America is fighting with itself about what kind of nation we will be.

Note which side has the better writers.