Monday

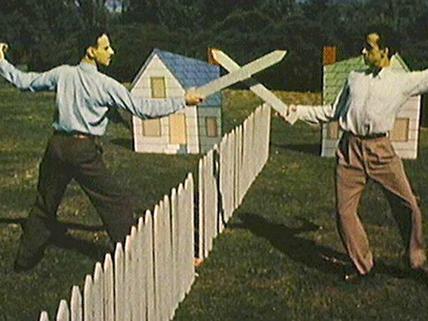

Although not one of the bigger news items these days, the strange case of a neighbor assaulting Kentucky Republican senator Rand Paul is puzzling pretty much everybody. Although the neighbor is a Democrat, everyone insists that the set-to was not political. New Yorker columnist Jeffrey Frank turned to a novel by Thomas Berger to figure out what actually happened.

We know what the effects of the battle were. Rene Boucher tackled Paul, causing six broken ribs and a pleural effusion. Some theorize that the battle was over property rights and lawn trimmings:

Jim Skaggs, the developer of Rivergreen, told the Louisville Courier-Journal that the two doctors, who have been neighbors for more than seventeen years, have a long and somewhat disagreeable history, much of it focussed on property rights. Although Skaggs was once the chairman of the Warren County Republican Party, he seemed to side with Boucher, whom he called a “near-perfect” neighbor, as opposed to Paul, who, he said, was less willing to go along with the regulations of the homeowners association “because he has a strong belief in property rights.” Skaggs thought that the breaking point came when Paul allegedly blew lawn trimmings into Boucher’s yard. “I think this is something that has been festering,” Skaggs said, mentioning past disagreements over who should cut down a tree branch when it stretched over a property line. The Times reported that Paul grows pumpkins, and composts.

Pumpkins and compost may well be at the root of things. This fall has been unusually warm in Kentucky, and the heat may affect decomposing organic matter in unpleasant, olfactory ways. Paul, who leans toward libertarianism, could well have considered the compost of a private gardener, on private property, to be an inalienable right, and one can sympathize with that view.

To borrow from Alexander Pope, can mighty contests rise from such trivial things? According to Berger’s novel Neighbors, they certainly can. Frank says that the novelist “understood the weird rages that spring up between people in close proximity”:

“I hope we can be friends,” Ramona, a new neighbor, tells the novel’s protagonist. “I’m sure we can,” he replies, to which Ramona says, “I didn’t mean that polite social kind of shit.” Berger’s characters seem less stable than the residents of Rivergreen, and the neighborliness-gone-bad is more ominous, as when he writes, “To have an outright enemy as one’s nearest neighbor, when one lived at the termination of a dead-end road, with only a wooded hollow beyond, a weed-field across the street, was unthinkable.”

Frank also unearths a lesson that Berger, when the novel came out in 1980, said that he learned from Kafka:

That at any moment banality might turn sinister, for existence was not meant to be unfailingly genial.

Maybe Frank is pushing things a bit when he extrapolates from the Paul-Boucher incident to America in general, but I’m willing to entertain the idea. Anyway, he thinks that such crankiness is spreading to a lot of Americans these days. A lot of neighbors seems to be squaring off these days:

The sinister banality of American life periodically moves into view, with a lot of it these days emanating from Donald J. Trump, the person who was elected President, a year ago.

Which neighbors, after all, is America not quarreling with these days—we can start with Mexico and Canada and then move on to old allies, such as Australia, Germany, and South Korea. Meanwhile, closer to home, many Alabamans say they would rather vote for a pedophile than for neighbors who are Democrats.

I’ve wondered for a while if electing Donald Trump was a sign of decadence more than anything else. Entertainment can take center stage when the economy is humming along and other people are fighting our wars. “Sinister banality” sounds like a wealthy nation problem.

As, for that matter, does a battle over lawn waste.