Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Thursday

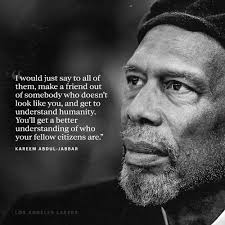

I always love learning about the favorite literary works of well-known figures as my mind instantly goes into motion to figure out why. Reading a blog post by basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, I learned that, growing up, he was a fan of one of my childhood favorites, Alexander Dumas’s The Three Musketeers. That tidbit appears in a wonderfully reflective essay about the importance of art in our lives. Here’s what Abdul-Jabbar has to say:

Most people remember books they read as children that opened their eyes to new possibilities and nudged them in a different direction in life. That, too, is the purpose of art.

For me, many books inspired me, but two books come immediately to mind. Alone in my room, I was barely a teen when I read Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers. It was exciting and suspenseful with lots of swordplay, intrigue, and betrayal. But it taught me something about teamwork, about being part of a group that was more important than the individual. I spent most of my youth and adulthood as part of a team in which we celebrated “All for one and one for all.” The passage occurs when D’Artagnan and the three musketeers decide to go all in on their feud with Cardinal Richelieu. You can see why a champion like Abdul-Jabbar would find it so thrilling:

“And now, gentlemen,” said D’Artagnan, without stopping to explain his conduct to Porthos, “All for one, one for all—that is our motto, is it not?”

“And yet—” said Porthos.

“Hold out your hand and swear!” cried Athos and Aramis at once.

Overcome by example, grumbling to himself, nevertheless, Porthos stretched out his hand, and the four friends repeated with one voice the formula dictated by D’Artagnan:

“All for one, one for all.”

“That’s well! Now let us everyone retire to his own home,” said D’Artagnan, as if he had done nothing but command all his life; “and attention! For from this moment we are at feud with the cardinal.”

The other book Abdul-Jabbar mentions, incidentally, is The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

It so happens that another fan of The Three Musketeers was W.E.B. Du Bois. In Souls of Black Folk, the great author, activist, and founder of the NAACP writes,

I sit with Shakespeare, and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm and arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out of the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed Earth and the tracery of stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the veil.

I devote a chapter to Du Bois in my forthcoming book Better Living through Literature because of the importance he attached to literature. Challenging African American authors to be courageous, in his essay “Criteria of Negro Art” he writes that

it is the bounden duty of black America to begin this great work of the creation of Beauty, of the preservation of Beauty, of the realization of Beauty, and we must use in this work all the methods that men have used before. And what have been the tools of the artist in times gone by? First of all, he has used the Truth — not for the sake of truth, not as a scientist seeking truth, but as one upon whom Truth eternally thrusts itself as the highest handmaid of imagination, as the one great vehicle of universal understanding. Again artists have used Goodness — goodness in all its aspects of justice, honor and right — not for sake of an ethical sanction but as the one true method of gaining sympathy and human interest.

In my book I speculate that Du Bois drew on the musketeers’ “all for one” slogan when he was founding the NAACP. Abdul-Jabbar has made me more confident in this speculation.

I’m pretty sure, from reading Abdul-Jabbar’s essay, that he is familiar with Du Bois’s writing on art and literature. And one point he writes that, whereas science shows us the possibilities of life and business the practicalities,

art shows us how to better enjoy life. What is the point of science prolonging life and business building better homes if we are miserable in that longer life and those comfortable homes?

Abdul-Jabbar opens his essay with a quote from Trappist monk, author and poet Thomas Merton—“Art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time’’—and talks about how it has worked this way on him. He says that art helped him in his identity quest, discovering “who I was and who I wasn’t,” and also made him realize that, to become part of a team that was bigger than him, he needed to lose his childish ego. And that’s not all that art has done for him:

Art helps one find the joy in life and reveals the source of pain so it can be addressed. But it also is a celebration of our individual and group values. We build statues of people we admire so that we can emulate them. We don’t always get it right, but like I just mentioned, getting it wrong is also part of the journey.

He also quotes Aristotle about how art helps us see beyond the outward appearance of things. And not only that. Art is also fun, he points out, citing a Richard Wilbur poem to make his point:

Finally, art is entertainment. It can be a delightful distraction from the daily dark of routine and struggles. A chance to catch our breath and regroup for tomorrow. That makes me think of the poem “The Juggler” by Richard Wilbur in which the audience watches the juggler juggling a table, a plate, and a broom—the symbols of their heavy daily responsibilities—as if they were weightless. When he’s done, the audience bursts into thunderous applause for lightening their load:

For him we batter our hands

Who has won for once over the world’s weight.

Here’s the poem in its entirety:

A ball will bounce; but less and less. It’s not

A light-hearted thing, resents its own resilience.

Falling is what it loves, and the earth falls

So in our hearts from brilliance,

Settles and is forgot.

It takes a sky-blue juggler with five red balls

To shake our gravity up. Whee, in the air

The balls roll around, wheel on his wheeling hands,

Learning the ways of lightness, alter to spheres

Grazing his finger ends,

Cling to their courses there,

Swinging a small heaven about his ears.

But a heaven is easier made of nothing at all

Than the earth regained, and still and sole within

The spin of worlds, with a gesture sure and noble

He reels that heaven in,

Landing it ball by ball,

And trades it all for a broom, a plate, a table.

Oh, on his toe the table is turning, the broom’s

Balancing up on his nose, and the plate whirls

On the tip of the broom! Damn, what a show, we cry:

The boys stamp, and the girls

Shriek, and the drum booms

And all come down, and he bows and says good-bye.

If the juggler is tired now, if the broom stands

In the dust again, if the table starts to drop

Through the daily dark again, and though the plate

Lies flat on the table top,

For him we batter our hands

Who has won for once over the world’s weight.

I like the way Wilbur describes applause as battering our hands. It is a reminder of “the daily dark” in which we spend much of our lives. Art gives us momentary reprieve, prompting Abdul-Jabbar to conclude with the following piece of advice:

As you venture forth today, notice the art that surrounds you, enlightens you, and lifts you. And rejoice.

Ditto to that.