Monday

I remember vividly when Muhammad Ali, who died Saturday, beat George Foreman in “the Rumble in the Jungle” (October 30, 1974). I was working as a reporter for a Winchester, Tennessee weekly, where I heard the n-word on a daily basis, especially from the newspaper’s publisher. More than anything, the publisher wanted Foreman to shut up this trash-talking black man. After all, he was (1) a Civil Rights activist, (2) an anti-war protester and (3) a Muslim. Like all of us, he was sure Foreman was going to tear Ali apart. In the end, of course, Ali was the one still standing.

The following day the publisher came in, shaking his head with deep disappointment but also with a sense of wonder. “The n_______ did it,” he said. In those days Muhammad Ali meant a lot to a lot of people, not all of it positive.

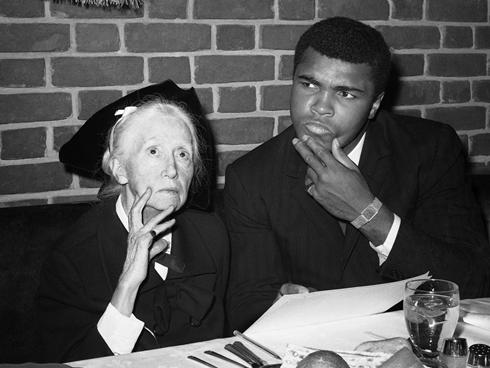

Looking for a literary angle on the athlete who was famous for spouting off doggerel, I came across a great article by Katy Waldman in Slate. She mentions how Ali has been described in one study as “the first heavyweight champion of rap,” with such memorable lines as “I done handcuffed lightning, thrown thunder in jail.” Along with his own poetry, he lifted others to poetic heights as well, including his cornerman Drew Bundini Brown’s famous description of him: “Floats like a butterfly, stings like a bee/Your hands can’t hit what your eyes can’t see.” He also inspired poet Marianne Moore, who wrote the liner notes for an album he released of his spoken word poetry.

The album appeared in 1963 when Ali was still Cassius Clay. Moore obviously gets a kick out of his hyperbole and, in response, indulges in some of her own. If he is “the greatest,” then why not compare him to William Shakespeare, Alexander Pope, and Sir Philip Sidney? There’s even an allusion to Thomas Gray’s “Elegy in a Country Churchyard” although only for contrastive purposes: Ali is not one to bloom unseen and waste his sweetness on the desert air. Here are the liner notes:

I AM THE GREATEST, if meant seriously, is comic, and if meant comically, is comic. It is romantic comedy, it is poetic drama. If it savors of diatribe, consider: “I worry not the danger, I have archly crossed the moor.” These rhyming couplets are a mode of verse, the New York Times says, for which more has been done here than by anyone since Alexander Pope. At a crucial moment—rather often indeed—altitude is saved by a hair from being the flattest, peanutiest, unwariest of boastings; saved one might say with Shakespeare, “by one of Caesar’s hairs.”

I AM THE GREATEST or MUCH ADO ABOUT CASSIUS has structure. Its hero, The Greatest—though a mere youth—has snuffed out “more dragons than Smokey the Bear hath.” Mighty-muscled and fit, he is confident, he is sagacious; even so, he trains, he fights: he is not ring-rusty, he acquires a title, a crown, a purse; a king’s daughter is bestowed on him as a fiancée–a princess. He is literary–in the tradition of Sir Philip Sidney, defender of Poesie. His verse is ornamented by alliteration. An official voice calls him: “Come forth, Cassius Clay.” A knight, a king of the ring, a mimic, a satirist, he calms his opponent: “Of course you’re tired and irritable. Control yourself.”

He has aplomb sufficient to impersonate Presidential “vigah.” He is not even deterred by “the small volks dragons.” He has a fondness for antithesis, will not only “give fighting lessons but falling lessons.” As The Greatest, he is, of course, master of hyperbole: his “punch raises his opponents clear out of the ring. The crowd is getting frantic. A radar station has picked him up. He is over the Atlantic.” Admittedly the “classiest and brassiest,” when asked, “How do you feel about the British calling you Gaseous Cassius,” his reply is one of the prettiest in literature: “I do not resent it.” He is a master of concision. Asked, “Have you ever been in love,” he says, “Not with anyone else.” Note this: beat grime revolts him. How not! Has any champion charm when beclouded by grime? He is neat, spruce; debonaire with manicure; his brow is high. If beaten–since mortal–he still is not “beat.” Might he, as winner, be Tel-elusive? Not so. He will be seen win or lose–in normal motion and slow. Could MUCH ADO, could The Greatest, disappear in desert air? “Anywhere at all?” Might “eight trillion” copies of I AM THE GREATEST be enough? No. He fights and he writes. Is there something I have missed? He is a smiling pugilist.

Moore doesn’t see Clay/Ali as entirely serious: he’s a hair away from altitude, by which I assume she means vanity. The passage about Caesar’s hairs is from Julius’s Antony famous funeral elegy where he says that people should beg a hair from Caesar to remember him by. Antony isn’t speaking entirely seriously here either—or rather, he’s saying one thing (“I come not to praise Caesar but to bury him”) but using his words for an entirely different agenda.

Maybe Julius Caesar comes to mind because of Clay’s first name at the time, although Moore doesn’t quote the most famous line about the leader of the conspirators: “Yond Cassius hath a lean and hungry look.” After all, Ali didn’t strike one as lean and hungry. He was more vibrant and alive.

The reference to Much Ado about Nothing may suggest that, at one level, Clay is bullshitting his audience. He’s pretending to make much ado about himself but it’s made up, just like the scandal at the heart of Shakespeare’s play.

Finally, because she is invigorated by Ali’s brashness, which would have been more startling in reticent 1963 than it would be today, Moore mimics it. She also conclude with a very Ali-type couplet:

He fights and he writes.

Is there something I have missed?

He is a smiling pugilist.

Waldman mentions that one could predict Moore’s admiration for Ali by reading her famous poem “The Octopus,” which compares ice-covered Mt. Ranier to an octopus. The poem then evolves so that one comes to realize that Moore is also writing about poetry: the mountain, like an octopus, comes upon us stealthily but then unleashes it power. In other words, mountains, poets and championship boxers all have something in common.

In the final stanza, when Moore talks about “neatness of finish,” you can imagine both a polished poem and a knock-out punch. The mountain moves stealthily until suddenly, without warning, we find ourselves entwined in its octopus arms and assaulted by winds that

tear the snow to bits

and hurl it like a sandblast

shearing off twigs and loose bark from the trees.

Then the trees themselves are leveled as an avalanche is launched “with a sound like the crack of a rifle.” The quotations, incidentally, are from a state park manual. Here’s the final stanza:

Neatness of finish! Neatness of finish!

Relentless accuracy is the nature of this octopus

with its capacity for fact.

‘Creeping slowly as with meditated stealth,

its arms seeming to approach from all directions,’

it receives one under winds that ‘tear the snow to bits

and hurl it like a sandblast

shearing off twigs and loose bark from the trees.’

Is ‘tree’ the word for these things

‘flat on the ground like vines’?

some ‘bent in a half circle with branches on one side

suggesting dust-brushes, not trees;

some finding strength in union, forming little stunted grooves

their flattened mats of branches shrunk in trying to escape’

from the hard mountain ‘planned by ice and polished by the wind’–

the white volcano with no weather side;

the lightning flashing at its base,

rain falling in the valleys, and snow falling on the peak–

the glassy octopus symmetrically pointed,

its claw cut by the avalanche

‘with a sound like the crack of a rifle,

in a curtain of powdered snow launched like a waterfall.’

The greatest boxers of the day saw that lightning flashing and found themselves buried under that curtain of powdered snow.