Friday

Here’s a literary comparison I never would have anticipated: Amelia Bedelia as a feminist Bartleby.

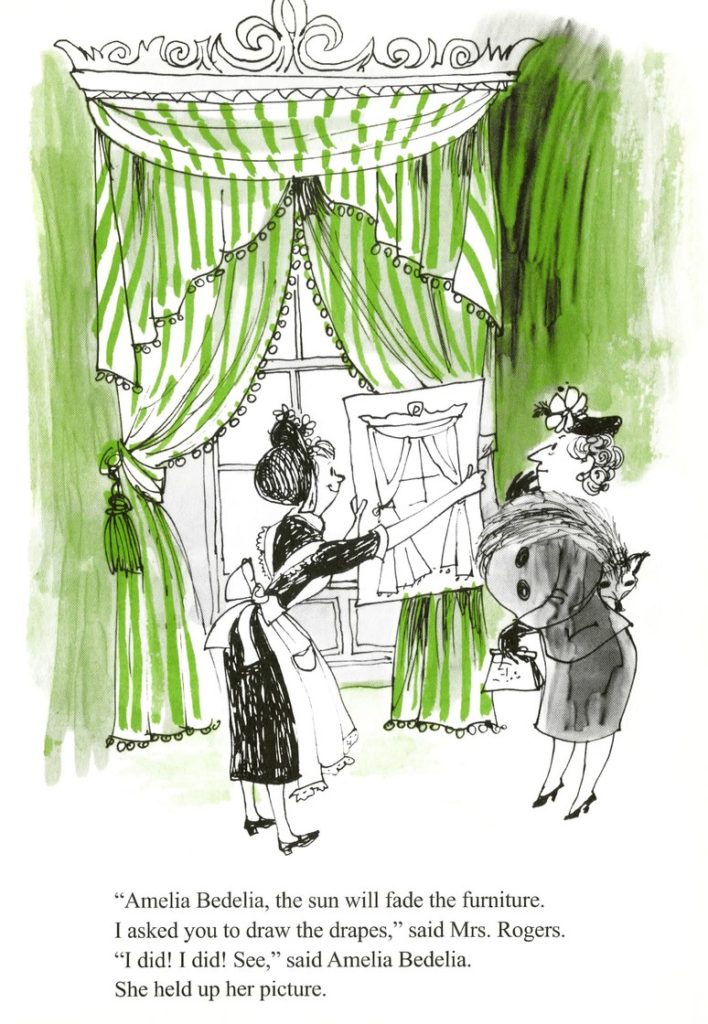

Reader Donna Raskin alerted me to this New Yorker article by Sarah Blackwood, who came up with the comparison after reading the series to her children. Amelia Bedelia is a maid who gets in trouble because she takes every command literally, whether drawing the curtains, dusting the furniture, or making the bed. Always on the verge of being fired, she repeatedly saves her job through her delicious cooking.

I’ve read one of the early books to my granddaughters and can report on their enthusiastic response. Children love playing with language, and commands that can be read two ways fascinate them. Our readings are very interactive, with them shouting to Amelia to get it right and delighting when she doesn’t.

Blackwood, while reporting a similar response from her children, takes the discussion in a more political direction. She points out that the series appeared in the early 1960s, coinciding with Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique. In her view, the work is a rebellion against mind-numbing labor. Whereas Bartleby rebels by withdrawing into passivity, however, Amelia does so by creating chaos. Blackwood notes,

When asked to “dust the furniture,” she sprinkles powder all over the living room; asked to “change the towels,” she takes scissors to them. She dirties and destroys her employers’ possessions, in other words, breaking one of the primary taboos of domestic employment. She’s a figure of rebellion: against the work that women do in the home, against the work that lower-class women do for upper-class women.

Now for the Bartleby comparison:

“I would prefer not to” is Bartleby’s famous refrain; if he took Amelia’s job, Bartleby would neither pull the drapes from the windows nor sketch them with pen and paper but sit and stare at them with stoic despondence. Melville’s story is one of American literature’s great tales of workplace degradation, and, though it takes place in an office, it is in some ways as domestic, as intimate, as a story about a household servant—Bartleby, increasingly depressed, begins sleeping and living at his workplace. But, where Bartleby responds to degradation by withdrawing, reducing, starving himself, Amelia Bedelia produces sugary excess. Throughout her daily grind, she cheerfully acquiesces to her lot even as she subverts almost every task assigned to her. Bartleby teaches us to look for resistance in forms of ascetic refusal; Amelia Bedelia turns passive aggression into a kind of art.

Author Peggy Parrish, who grew up in an impoverished family but went on to college and taught third grade at the upper-class Dalton School, could well be rebelling against menial work. Blackwood points out that the first book appeared at the dawn of the feminist movement:

The first Amelia Bedelia book was published in 1963, the same year as Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique; the series’ interest in wordplay, literalism, and figurative language is of a piece with its interest in the repetitive, devalued, yet highly intimate quality of women’s work. Perhaps more than other forms of work, domestic labor is often misnamed as love, duty, or some kind of irresistible biological calling. And that’s when it’s named at all; women’s work—the cooking, appointment-keeping, party-planning, soap-dispenser-refilling—is so often invisible. Parish’s books spotlight this labor, and refuse the sentimental fuzziness that usually attends it (especially when it is attached to a mother figure). In Come Back, Amelia Bedelia (my favorite), Mrs. Rogers is pushed to her limit when, having asked for coffee and cereal for breakfast, Amelia brings her a cup of coffee with cereal mixed into it. “Oh, you are impossible!” Mrs. Rogers exclaims. “You’re fired!”

The Bartleby comparison is strained, however, and Amelia reminds me more of Alice. Both are innocent and, like Amelia, Alice inadvertently causes mayhem, undermining suffocating Victorian child-rearing practices by unconsciously botching recitations, insulting various characters, and exposing the strangeness of the adult world. The world of nonsense flourishes when the world of sense becomes too constricting.

Other “sweet” characters in children’s books have their own ways of rebelling. “Sally and I” may be innocent, but their alter egos, Thing 1 and Thing 2, trash the house, overriding the protests of their inner fish conscience. Madeleine disrupts the straight lines of Miss Clavel, Francis tests bedtime rules and her parents’ tolerance, and George messes up only because he is “too curious.”

When the world doesn’t make sense to children, stories are there to capture their confusion. Since America’s extreme income inequality shouldn’t make sense to any of us, Amelia Bedelia’s rebellion speaks for us all.