Monday

My son gave me a tough-love talk about my writing at a wedding reception this past Saturday afternoon. We were in Iowa together for my wife’s nephew and Darien took a few moments to express doubts about book he is helping me self-publish.

While he is a big supporter of the blog, he worries that a collection of past blog essays devoted to Trump and the Trump Resistance turns the president into a bigger-than-life figure. Doesn’t comparing Trump to (among many others) Willie Stark, King Lear, Macbeth, Milton’s Satan, and Melville’s Confidence Man make a boring man interesting? If you want to understand Trump, my businessman son informed me, hang out with a group of “Wall Street bros” and you’ll see that he’s motivated by nothing more complicated than “my steak is bigger than your steak.”

In other words, Trump perpetually engages in primitive dominance rituals and, unlike these literary figures, that’s all that there is to him. We see none of Satan’s expressed doubts and self-loathing, none of Macbeth’s existential despair, none of Lear’s capacity for redemption.

Darien’s point, which I take seriously, reminds me of John Arbuthnot criticizing Alexander Pope for satirizing Lord John Hervey, a scandal-mongering courtier. When Pope declares that he will compare Hervey to Emperor Nero’s eunuch lover Sporus and make him his next target, he imagines Arbuthnot objecting. Pope speaks first, then Arbuthnot:

Let Sporus tremble—"What? that thing of silk,

Sporus, that mere white curd of ass's milk?

Satire or sense, alas! can Sporus feel?

Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel?"

Yet let me flap this bug with gilded wings,

This painted child of dirt that stinks and stings…

Am I indeed breaking a butterfly on a wheel in my many blog posts about Trump? It’s certainly possible.

Actually, since one of the most powerful men in the world can’t be dismissed as a butterfly, a work that parallels Darien’s criticism more exactly may be a Borges short story in which a detective turns a crime into something much more complicated than it actually is. In “Death and the Compass,” a rabbi poring over ancient texts in a hotel room has been stabbed in what appears to be a random murder. Detective Treviranus, resembling Scotland Yard’s Tobias Gregson in the Sherlock Holmes stories, thinks the murderer blundered into the wrong room since there were jewels to be stolen in the room next door. The Sherlock-like Lonnrot will have none of it:

“There’s no need to look for a Chimera, or a cat with three legs,” Treviranus was saying as he brandished an imperious cigar. “We all know that the Tetrarch of Galilee is the possessor of the finest sapphires in the world. Someone, intending to steal them, came in here by mistake. Yarmolinsky got up; the robber had to kill him. What do you think?”

“It’s possible, but not interesting,” Lonnrot answered. “You will reply that reality hasn’t the slightest need to be of interest. And I’ll answer you that reality may avoid the obligation to be interesting, but that hypotheses may not. In the hypothesis you have postulated, chance intervenes largely. Here lies a dead rabbi; I should prefer a purely rabbinical explanation; not the imaginary mischances of an imaginary robber.”

Something similar could be said about literature, which also has the obligation to be interesting, even if reality doesn’t.

Treviranus is understandably annoyed. “I am not interested in rabbinical explanations,” he says. “I am interested in the capture of the man who stabbed this unknown person.”

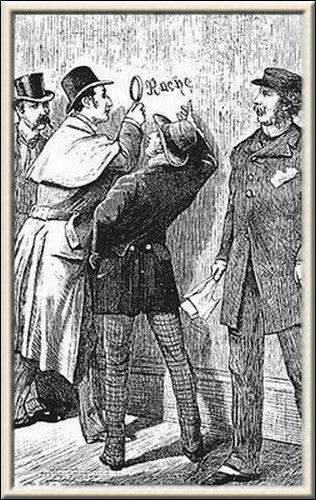

In Arthur Conan Doyle’s Study in Scarlet, Inspector Gregson sees “Rache” written on the wall next to a murder victim and assumes that a woman named Rachel is involved. The perceptive Holmes, by contrast, figures out that “Rache” is actually the German word for revenge.

In the Borges short story, however, the Gregson figure turns out to be right: the murderer did in fact stumble into the wrong room. In a further twist, the robber chief who ordered the theft sees what Lonrot is up to and feeds him with false clues to encourage him in his elaborate theories. In the end, he lures the detective to an out-of-the-way locale and, after revealing what he has done, shoots him.

I’ll further pursue whether I am a Lonrot when it comes to Trump in a further post. The question is worth exploring since the media too has been accused of something similar, giving so much attention to this “painted child of dirt that stinks and stings” that it helped elevate him. Stay tuned.