Monday

We’re in full strawberry season at the moment, and the strawberry coffee cake that my wife made for yesterday’s church coffee hour—with strawberries she picked from the college farm—disappeared in an instant. Thoughts of literary strawberries took me to Jane Austen’s Emma, although when I first looked at the strawberry picking scene, I was confused. It shows up in a long paragraph that opens in one vein and ends in another. Something seems amiss.

I have learned to always trust Austen, however. If a sentence seems awkward, there is always—and I mean always—a reason for it. And so it has proved to be the case here.

Mrs. Elton, Emma’s social-climbing foil, has wheedled an invitation out of Mr. Knightley to invite people over to pick strawberries from his premier beds. Being a gentleman, Knightley can’t refuse, although he insists on doing it on his terms. Despite Mrs. Elton’s suggestion, there will be no outdoor picnic. They will pick strawberries and then go indoors for a luncheon.

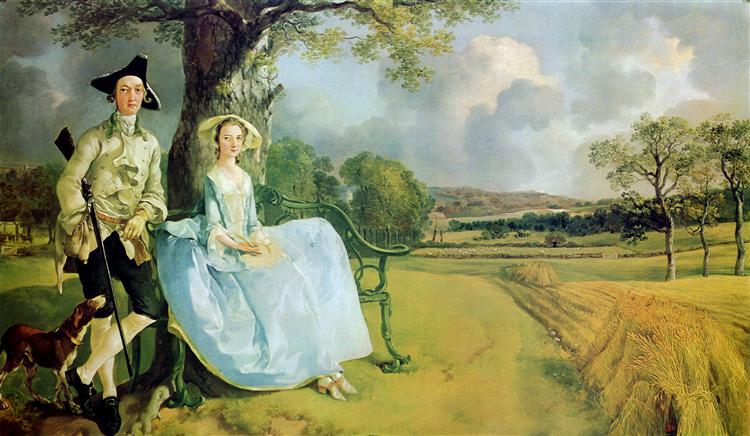

Austen is taking a dig at idyllic views of nature here. Mrs. Elton has visions of a pastoral setting, with herself carrying around a basket with pink ribbons, riding in on a picturesque donkey, and, Marie-Antoinette like, playing the dairymaid—or in this case, the strawberry picker. Austen is always suspicious of such shallow Romanticism. .

In any event, Mrs. Elton at least gets a Donwell Abbey invitation and comes prepared to lord it over everyone.

And Emma? She’s looking forward to seeing Donwell again. Her sister has married Knightley’s brother, and her long friendship with Knightley makes her proud to have such an acquaintance. Upon arriving, she takes a tour of the grounds.

The paragraph that confused me begins with her reflections and ends with an account of the strawberry picking, conveyed entirely through snippets of Mrs. Elton’s non-stop comments. Here the paragraph, along with the lead in:

It was so long since Emma had been at the Abbey, that as soon as she was satisfied of her father’s comfort, she was glad to leave him, and look around her; eager to refresh and correct her memory with more particular observation, more exact understanding of a house and grounds which must ever be so interesting to her and all her family.

She felt all the honest pride and complacency which her alliance with the present and future proprietor could fairly warrant, as she viewed the respectable size and style of the building, its suitable, becoming, characteristic situation, low and sheltered—its ample gardens stretching down to meadows washed by a stream, of which the Abbey, with all the old neglect of prospect, had scarcely a sight—and its abundance of timber in rows and avenues, which neither fashion nor extravagance had rooted up.—The house was larger than Hartfield, and totally unlike it, covering a good deal of ground, rambling and irregular, with many comfortable, and one or two handsome rooms.—It was just what it ought to be, and it looked what it was—and Emma felt an increasing respect for it, as the residence of a family of such true gentility, untainted in blood and understanding.—Some faults of temper John Knightley had; but Isabella had connected herself unexceptionably. She had given them neither men, nor names, nor places, that could raise a blush. These were pleasant feelings, and she walked about and indulged them till it was necessary to do as the others did, and collect round the strawberry-beds.—The whole party were assembled, excepting Frank Churchill, who was expected every moment from Richmond; and Mrs. Elton, in all her apparatus of happiness, her large bonnet and her basket, was very ready to lead the way in gathering, accepting, or talking—strawberries, and only strawberries, could now be thought or spoken of.—“The best fruit in England—every body’s favorite—always wholesome.—These the finest beds and finest sorts.—Delightful to gather for one’s self—the only way of really enjoying them.—Morning decidedly the best time—never tired—every sort good—hautboy infinitely superior—no comparison—the others hardly eatable—hautboys very scarce—Chili preferred—white wood finest flavour of all—price of strawberries in London—abundance about Bristol—Maple Grove—cultivation—beds when to be renewed—gardeners thinking exactly different—no general rule—gardeners never to be put out of their way—delicious fruit—only too rich to be eaten much of—inferior to cherries—currants more refreshing—only objection to gathering strawberries the stooping—glaring sun—tired to death—could bear it no longer—must go and sit in the shade.”

I fully expect the paragraph to end at the point where Emma joins the party, but it continues on. I think it does so because Austen wants the two halves to clash with each other. In the first half, the sentences are ordered and sedate. The abbey and its grounds reflect the good taste of its owner.

Mrs. Elton is an entirely different matter. She begins with inane small talk but, because she can never talk about something without making demeaning comparisons, she very soon launches into talking about different kinds of strawberries and which are superior—hautboys, Chilean strawberries, or white wood strawberries. Somehow her monologue gets around, as it always does, to her hometown of Maple Grove. Then, next thing we know, she’s putting down strawberries in favor of cherries, which then give way to currants. Then she’s complaining about stooping and the heat—so much for idyllic nature—and by the end she is “tired to death—could bear it no longer—must go and sit in the shade.”

So what’s Austen up to? As a vulgar social climber in the presence of gentry (Knightley, Emma), Mrs. Elton is the worm in the apple, the toad in the garden. Austen doesn’t say so directly, but Mrs. Elton’s strawberry monologue is just more proof that she lacks the class of her social superiors.

My favorite example of the contrast, which is a constant theme in the novel, appears in the final paragraph when Mrs. Elton lets us know what she thinks of Emma’s wedding dress—which she knows about because her husband performs the ceremony:

The wedding was very much like other weddings, where the parties have no taste for finery or parade; and Mrs. Elton, from the particulars detailed by her husband, thought it all extremely shabby, and very inferior to her own.—“Very little white satin, very few lace veils; a most pitiful business!

We can imagine that her own wedding was gaudy and tasteless in the extreme.

Note how Austen carves up Mrs. Elton by showing, not telling. Years ago I remember reading an article discussing Austen’s indirect style. The author, whose name I can’t remember, noted that Gustave Flaubert is often given credit for indirect style in Madame Bovary, which appeared in 1856. Emma appeared in 1815, over 40 years earlier, and the article’s point was that she should be given more credit as a revolutionary stylist. After all, most authors of the time—including Austen in earlier novels and even occasionally in Emma—intervene in their novels. In any event, Austen is breaking new stylistic ground here.

I have to say that Austen’s distaste for social climbers, which shows up in most of her novels, is my least favorite thing about her. Think Isabella Thorpe, Lucy Steele, Caroline Bingley, Mrs. Elton, and Mrs. Clay. (Only Mansfield Park, with its focus on the young, rich, and restless, seems to lack a social climber.) Austen’s distaste, I think, comes from her anxiety about her own class status, which was perilously close to middle class. But putting that aside, she certainly knows how to wield her satiric pen when creating such figures.