Tuesday

Along with Ukraine’s horrific war with Russia, there’s a secondary battle unfolding in the country, one involving statues and street names honoring poets. Trivial though that may sound in light of Russia’s genocidal slaughter, as I’ve been noting it’s actually attempted genocide in a different key. Having seen literature used to erase their identity, the Ukrainians are now taking shots at monuments to that literature.

I’ve pointed out (here and here) that Russia has long exploited the fact that some world-class Ukrainian authors have chosen to write in Russian, thereby affirming (in Russian eyes) that Ukrainians are really Russians—and that therefore Russian interference in Ukraine is justified.

There have Ukrainian authors, on the other hand, who have chosen to write in Ukrainian, thereby legitimating both the language and the nation that speaks it. If Ukrainians honor the poet Shevchenko, including with a large statue that overlooks Karkhiv’s city center, it’s because they say that, through his Ukrainian language poetry, he dreamed the nation into existence.

So welcome to the battle of memorials.

A Washington Post article notes some of the Russian memorials, including one in a city now known world-wide as the site of horrific Russian war crimes against the civilian population:

Reminders of Russian and Soviet dominion can be found almost everywhere in Ukraine. A street in Bucha is named after Alexander Pushkin, a poet revered by Russians as their Shakespeare. The 19th-century novelist Nikolai Gogol — who was born in Ukraine but claimed by Russia as one of its greatest authors because he wrote in Russian — overlooks one of Dnipro’s main boulevards from a pedestal.

As I noted in a recent post, Gogol’s decision to write in Russian was a big deal for Russian émigré Vladimir Nabokov, showing the nature of Russian literary chauvinism. Here’s from an article that appeared in Literary Hub:

“We must thank fate (and the author’s thirst for universal fame) for his not having turned to the Ukrainian dialect as a medium of expression, because then all would have been lost,” wrote Vladimir Nabokov in his 1959 study, Gogol. He continued: “When I want a good nightmare, I imagine Gogol penning in Little Russian dialect volume after volume….” What he calls the “Little Russian dialect” is none other than the Ukrainian language, which is about as close to Russian as Spanish is to Italian.

I’ve also written on a Josef Brodsky poem that, part satirically but maybe not entirely, contrasts the “bullshitter” Shevchenko with the immortal Pushkin.

And then there is Bulgakov, author of The Master and Margarita and The Heart of a Dog, who though born in Kyiv chose to write in Russian. Not only that, the Post reports, but “he maligned Ukraine’s national aspirations and had the gall to disparage its mother tongue.”

So now Ukrainians are looking at what to do with the various memorials. According to the Post article, there is a new social media tool called “What did Pushkin do to you?” One types in a name and gets mini-tutorials on why various Russian figures should stay or go:

Tap Puskhin’s name, and the Telegram bot spits out a verdict writing him off as a “Russian chauvinist” who glorified czarist imperialism. It says much the same about Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

Apparently the tool grants passes to Tolstoy and Chekhov “because of their humane and empathetic approach to almost everything they wrote.”

According to Yaroslav Hrytsak, director of the Institute for Historical Studies of Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Russian and Soviet markers have functioned as “a kind of imperial wallpaper” in Ukraine:

“I accepted it as a dull Soviet landscape,” Hrytsak said. It was as if street by street and square by square, the Soviet Union had all but lobotomized historical memory in Ukraine and other former republics, he said.

“Ukrainians were denied any kind of memory that would make them different from Russians,” Hrytsak said. “The politics of the Soviet Union toward Ukraine was a total amnesia.”

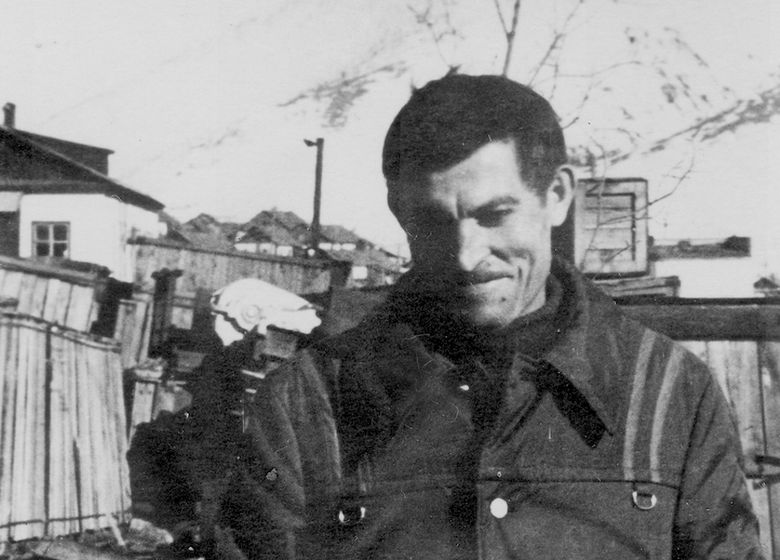

So if Pushkin and Gogol come down, who will take their place. One possibility mentioned in the article is Vasyl Semenovych Stus, a poet who died in a Soviet gulag while on a hunger strike in 1985. I did some googling on Stus and found a fascinating piece on him in the Los Angeles Review of Books. Here’s some material about him:

Following his arrest for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” in 1972, Stus spent nine months in custody awaiting his trial. During this period he composed a major collection, Time of Creativity (later to become part of Palimpsests), the title of which communicates the choice he had made: to keep creating against all odds. In almost complete solitude, broken only by interrogations, Stus wrote more than 300 original poems and translated more than 100 poems by Goethe. The dates under Stus’s poems show that he sought to write at least one poem a day; some days he wrote as many as five.

And then there’s this:

The Jewish-Ukrainian dissident Semen Gluzman, then a young psychiatrist and now the head of Ukraine’s Association of Psychiatrists, spent 20 days with Stus in custody. On first entering the cell, he saw a 30-year-old man bent over a bedside table with a book of poetry and an open dictionary. In the “feast of conversations” that followed, Stus would speak at length about philosophy and literature, recite poetry from memory, and read out his translations of Rainer Maria Rilke. The cell Gluzman shared with Stus came to seem spacious and full of light, because the poet refused to allow it to suffocate their minds. “Over these prison walls, over this sorrow, / and over Sophia’s bell tower my spirit lifts me,” he wrote while imprisoned in the KGB building located jarringly close to the ancient Saint Sophia’s Cathedral in Kyiv. In another poem from this period he extends his spiritual flight, transcending the earthly realm altogether:

Earth is too small

for the spirit. Too cramped

for the dishevelled soul is this planet,

where dwelling is but hunching (the trenches

of self-elevations)Where did Stus find the strength for this flight? The answer lies in one of his neologisms: samosoboiunapovnennia, “filling-oneself-with-oneself.” Stus uses the word in the very first poem he wrote in captivity, which starts with a star shining at dawn and ends with an epiphany: “for living means not overcoming limits / but adjusting and filling-oneself-with-oneself.”

I’m not saying that Stus is as great as Gogol—but Ukrainians undoubtedly are inspired by how he faces up to adversity, of which they are getting more than their share at the moment. And just because Shevchenko is not as great as Pushkin doesn’t mean that he can’t be more meaningful. After all, if Russians have used Pushkin as a cultural club, then they have already drained him of his poetry.

There may come a time, when Ukraine is free of the invaders and has reestablished itself as a multi-lingual republic, where Ukrainians will find their way back to Russian-language literature. But right now what they need are poets who speak to them in Ukrainian with a Ukrainian desire for freedom.

Further note: I see fro Stus’s Wikipedia page that there are, in fact, many Ukrainian streets named after him. No surprise there. And those street names, it appears, will be there to stay.

And to emphasize just how important such street naming is–and how Russians desecrate Pushkin and others when they use them to support imperial ambitions–here’s a report from Julia Davis, who monitors Russian television:

More genocidal talk on Russian state TV: falsely claiming that Ukrainians are just Russians who need to be reminded that the Ukrainian language, history and religion are “made up,” that Russian troops in Ukraine are fighting for “their land” and Russia is planning to never leave.