Thursday

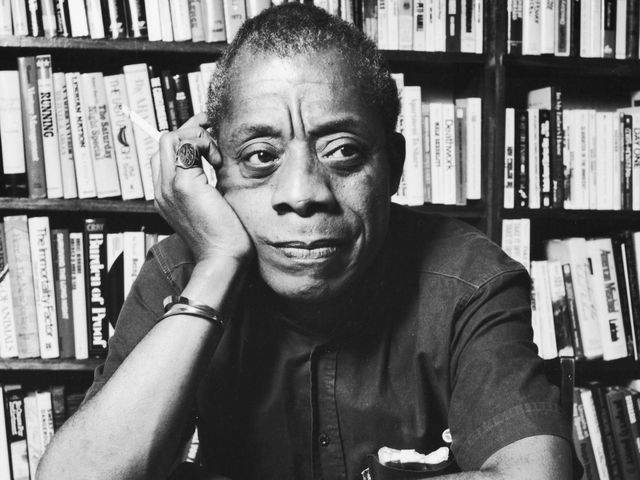

Teachers desiring inspiration as they launch into a new year should check out a New Yorker essay that appeared a year ago. An English teacher explains how a Baldwin essay propelled him to use classroom literature to address pressing social issues.

As Clint Smith saw it last September, here’s the dilemma that teachers face:

Students have returned to school after a summer of political and social tumult. In August, white supremacists and neo-Nazis brazenly marched across the campus of the University of Virginia; one shot at a counter-protester, and another mowed down a crowd with a car, killing a woman who had showed up to oppose their hate. A few weeks later, the White House announced that it would be rescinding the protections set in place by President Barack Obama’s daca program—a move that left eight hundred thousand undocumented immigrants uncertain about their futures. Many teachers are wondering how to address these events in their classrooms. Should they incorporate potentially contentious issues into their lessons? Should lessons be pushed aside to tackle the urgent matters of the day?

Regular readers of this blog know how I would respond: literature has always addressed the most “urgent matters of the day” and can continue to do so if we think of poems, plays and novels as living documents. In other words, the lessons shouldn’t be pushed aside but redirected. Smith says that Baldwin’s 1963 essay “A Talk to Teachers” shows how American history can be taught so that we come to a more honest reckoning with it:

“I would try to make him know that just as American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it, so is the world larger, more daring, more beautiful and more terrible, but principally larger—and that it belongs to him,” he writes, adding, “I would teach him that he doesn’t have to be bound by the expediencies of any given administration, any given policy, any given morality, that he has the right and the necessity to examine everything.”

Smith says that, after reading this essay, he “altered my approach, placing less emphasis on the standardized tests and using literature to help my students examine their world”:

I realized that rigorous lessons were not mutually exclusive from culturally and politically relevant ones. Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar did not have to be sacrificed in order to make room for a discussion on community violence. Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man did not have to be abandoned in order to tackle immigration. “A Talk to Teachers” showed me that a teacher’s work should reject the false pretense of being apolitical, and, instead, confront the problems that shape our students’ lives.

Smith links to his own New Yorker essay on the applicability of Invisible Man to our times, and it’s a work I too have turned to it time and again—how it could be used to process the killing of Trayvon Martin, the DACA kids hiding in the shadows, the excesses of the rightwing Congressional “Freedom Caucus,” the white backlash against Barack Obama, and even whitesplaining.

I wish Smith had been more specific about how he taught Julius Caesar, but scenes of community violence can be found in the stabbing of Caesar and the mob killing of the innocent poet Cinna. Following the Boston Marathon bombing, I invoked the play on how not to respond to terrorist attacks.

Smith concludes,

“A Talk to Teachers” showed me that a teacher’s work should reject the false pretense of being apolitical, and, instead, confront the problems that shape our students’ lives.

The most quoted line from “A Talk to Teachers” may be this one: “The paradox of education is precisely this—that as one begins to become conscious one begins to examine the society in which he is being educated.” A teacher, Baldwin believed, should push students to understand that the world was molded by people who came before, and that it can be remolded into something new.

One cannot always know how a work will touch upon issues students care about—a fair amount of serendipity is involved—but, by listening to one’s students and listening to the work, one will find many occasions to bring the two together. Then the world will become larger and genuine learning will occur.

One Trackback

video youtube indonesia

“[…]Baldwin: Making Lit Relevant | Better Living through Beowulf[…]”