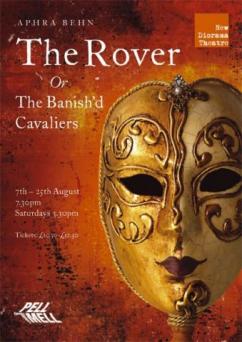

My students have been clarifying for me the radicalism of Aphra Behn’s 1677 comedy The Rover. Although Behn masks her egalitarian vision with humor, the play articulates how hard it was for a brilliant and independent woman to hold her own in the public arena.

The play is about two sisters, Florinda and Hellena, who long for other futures than the ones decided by their father. Florinda wants to marry the dashing Belvile rather than the old and wealthy Don Vincentio, while Hellena wants to marry Willmore (the rover of the title) rather than spend her life in a convent. Since it’s a comedy, both eventually get what they want, with Hellena becoming a bit of a rover in her own right. They first have to overcome a series of very revealing obstacles, however.

In her attempts to run away with Belvile, Florinda is almost raped twice by his friends. Meanwhile Willmore, one of these friends, doesn’t want to be tied down by any woman. He first wins the love of the high-priced courtesan Angellica, who waives her fees for him, and then, when he tires of her, chases after Hellena. Hellena’s challenge is to land him in marriage without him experiencing marriage as a trap. She succeeds after first dressing as a gypsy and then as a man before finally engaging in a dazzling verbal duel.

In a departure from the normal comic formula, we are also made to feel for the broken-hearted Angellica. Another prostitute, this one played for laughs, is the minor character Lucetta, who tricks the wannabe rake Blunt by pretending that she’s a great lady bestowing favors on him. In the end she strips him of his clothes and his money.

The four women students who wrote on the play all appreciated Behn’s exploration of women’s limited options. Tessa Haynes, who has written penetrating essays for me in the past (such as this one on Twilight and Jane Eyre), began her essay with a personal experience that explains why she found Behn so liberating:

I learned at a young age what could happen if I found myself walking alone late at night. I learned what could happen if I left a drink unattended at a party. I learned ways to prevent unwanted advances or attacks; keys between fingers, pressure points on hands and wrists to be released from a grip, and a companion for walking, preferably someone strong and aggressive looking. Women have had to become physical warriors in order to guard what society has deemed their most prized possession; the baby maker between their legs. The horrible thing is that there is nowhere that is truly safe. I had a friend who was assaulted at a party. I had a friend who was assaulted at a wave pool. I had a friend who was assaulted in her own home. We hear the stories, we see the statistics, and we arm ourselves for a battle we shouldn’t have to fight. This constant state of danger is not a recent thing for women. We’ve been experiencing it since the beginning of time. With the emergence of the internet and other media platforms as well as the dawn of feminism, this danger has been able to be clearly expressed to the world. Before this, women learned of the dangers from their mothers, close friends, and sometimes hidden within the writings of fellow women. Aphra Behn’s comedy The Rover is one of these writings.

As Tessa and the other women students see it, Behn too is frustrated by the constant threat of male assault. Each of the four female characters finds a modicum of power but each also runs up against the limitations of her gender.

Lucetta and Angellica, the two prostitutes, treat sex as a business proposition, which gives them some power (although Lucetta is working for a pimp). Angellica, however, wants something more: she wants love. Unfortunately, the moment that she allows herself to be vulnerable, she is used and then tossed. She regains some of her dignity toward the end by threatening to shoot Willmore and then just surrendering him as not worth the bother, but she’s been taught a stern object lesson.

Florinda hopes to be rewarded for being a virtuous woman. She rebels slightly—she runs away from her father and brother so that she can marry that man that she loves—but after that, as her name implies, she hopes that being a beautiful flower will be enough.

Behn rips that illusion away by having her almost raped, first by Willmore and then by Blunt, the latter because he wants all women to pay for Lucetta’s deceit. Florinda learns the hard way what Lucetta and Angellica already know: once you’ve slipped out of patriarchy’s protections, you are free game for any man.

Because Rover is a comedy, Florinda is saved—three times in all—but the almost-rape scenes are unusual for comedy and very unsettling. One doesn’t find such moments in male-authored plays. Here’s the dialogue in one of them:

Flor. ’Tis not my Belvile—good Heavens, I know him not.—Who are you, and from whence come you?

Will. Prithee—prithee, Child—not so many hard Questions—let it suffice I am here, Child—Come, come kiss me.

Flor. Good Gods! what luck is mine?

Will. Only good luck, Child, parlous good luck—Come hither,—’tis a delicate shining Wench,—by this Hand she’s perfum’d, and smells like any Nosegay.—Prithee, dear Soul, let’s not play the Fool, and lose time,—precious time—for as Gad shall save me, I’m as honest a Fellow as breathes, tho I am a little disguis’d at present.—Come, I say,—why, thou may’st be free with me, I’ll be very secret. I’ll not boast who ’twas oblig’d me, not I—for hang me if I know thy Name.

Flor. Heavens! what a filthy beast is this!

Will. I am so, and thou oughtst the sooner to lie with me for that reason,—for look you, Child, there will be no Sin in’t, because ’twas neither design’d nor premeditated; ’tis pure Accident on both sides—that’s a certain thing now—Indeed should I make love to you, and you vow Fidelity—and swear and lye till you believ’d and yielded—Thou art therefore (as thou art a good Christian) oblig’d in Conscience to deny me nothing. Now—come, be kind, without any more idle prating.

Flor. Oh, I am ruin’d—wicked Man, unhand me.

Will. Wicked! Egad, Child, a Judge, were he young and vigorous, and saw those Eyes of thine, would know ’twas they gave the first blow—the first provocation.—Come, prithee let’s lose no time, I say—this is a fine convenient place.

Flor. Sir, let me go, I conjure you, or I’ll call out.

Will. Ay, ay, you were best to call Witness to see how finely you treat me—do.—

Flor. I’ll cry Murder, Rape, or any thing, if you do not instantly let me go.

Will. A Rape! Come, come, you lye, you Baggage, you lye: What, I’ll warrant you would fain have the World believe now that you are not so forward as I. No, not you,—why at this time of Night was your Cobweb-door set open, dear Spider—but to catch Flies?—Hah come—or I shall be damnably angry.—Why what a Coil is here.—

Flor. Sir, can you think—

Will. That you’d do it for nothing? oh, oh, I find what you’d be at—look here, here’s a Pistole for you—here’s a work indeed—here—take it, I say.—

Flor. For Heaven’s sake, Sir, as you’re a Gentleman—

Will. So—now—she would be wheedling me for more—what, you will not take it then—you’re resolv’d you will not.—Come, come, take it, or I’ll put it up again; for, look ye, I never give more.—Why, how now, Mistress, are you so high i’th’ Mouth, a Pistole won’t down with you?—hah—why, what a work’s here—in good time—come, no struggling, be gone—But an y’are good at a dumb Wrestle, I’m for ye,—look ye,—I’m for ye.—[She struggles with him.

As Behn sees it, this is how men are. Hellena, who sets her sights on Willmore, has no illusions that he will respect her virtue. She knows, from Angellica’s example, that she can’t let her guard down. Her solution is verbal pyrotechnics that keep him intrigued, and their dialogue veers into Beatrice and Benedict territory from Much Ado about Nothing. Although Hellena insists on marriage because she doesn’t want “a cradle full of mischief and a pack of repentance on my back,” nevertheless she assures Willmore that their marriage will be like no other. She will never be predictable but will keep him off balance at all times. Because she threatens an inconstancy to match his own, he will never be able to ignore her.

This is not a great model for a marriage but it functions well as a comic resolution. Also, it is the best that Behn can come up with given the way that unmarried men seem perpetually predatory and patriarchal marriage appears a prison. Comedy allows room for imagining something beyond prevailing reality.

A couple of my students applied Northrup Frye’s vision of comedy to The Rover. As Frye describes the basic plot of comedy, there are three stages:

–Existent Society: existing society precludes hero from something he wants

–Confrontation: hero confronts representatives of society

–Reformation or Replacement of Society: the hero’s society replaces the previous society

In this case, the existing society denies women the freedom to enter into lasting and loving relationships. Men must be confronted and persuaded to change. Willmore’s and Hellena’s tumultuous coupling, where she gives him the promise of perpetual excitement and he treats her as an equal, is put forward as a replacement.

Behn dreams big but couches her vision in a form that can be laughed off. Best to be safe, she figures. Also, this way men will listen to her.