Wednesday

I’m worried that we’re replaying 1968, that horrific year of war, riots, and assassinations that culminated in the election of Richard Nixon. There’s a significant difference, however: back then, it was easier for Nixon and other such politicians to characterize the rioters as a black mob, devoid of individual characteristics. I believe it’s more difficult to do that now.

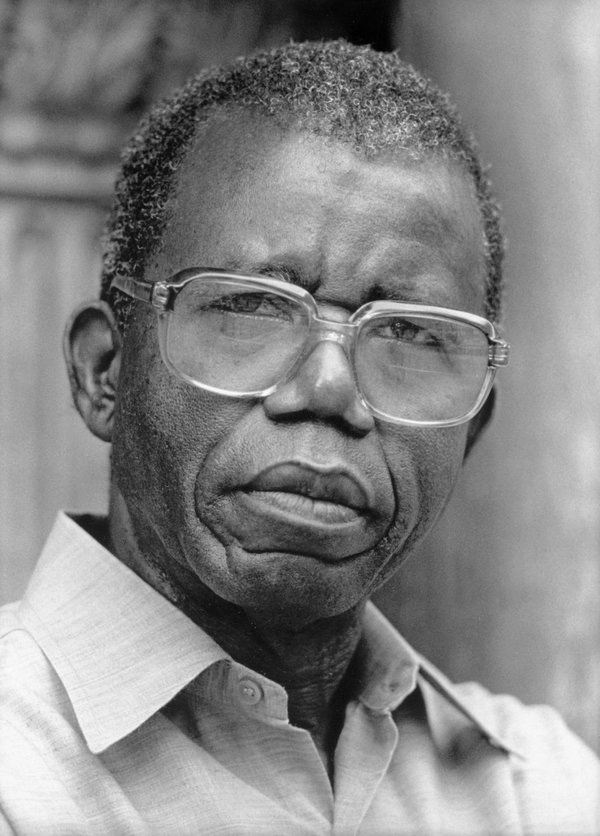

Helping change that perception has been Nigerian author Chinua Achebe’s 1977 critique of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902). While most Americans have never heard of Achebe, his essay “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,” or even Heart of Darkness itself, the Achebe-Conrad debate is foundational reading in many literature departments. (The texts, along with Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart, all appear in the second volume of the Norton Anthology of English Literature.) Those who teach required Composition and Intro to Literature classes have been shaped by the debate, even when they don’t teach the works, and those classes have in turn influenced the way that humanities, social science, science, and professional departments talk about race.

In their turn, graduates have gone out to change workplaces. To look just at television news, one sees far more reporters of color, commentators of color, and expert guests of color, whose presence and articulate views undermine stereotypes. Trump worshippers and reactionary police may lump everyone together, but I’m noticing considerably more pushback from the media than I saw 50 years ago.

Cell phone cameras have also changed the conversation. One can see, for instance, that many of the rioters, vandals and looters have been white, not black, and we’re even seeing black protesters confronting white vandals, whom they accuse of smearing them. Trumpists may not be open to racial nuance, but America increasingly is.

Let’s therefore go back to Achebe’s essay, which objects to the narrator’s vision of Africans. He targets the following passage:

We were wanderers on a prehistoric earth, on an earth that wore the aspect of an unknown planet. We could have fancied ourselves the first of men taking possession of an accursed inheritance, to be subdued at the cost of profound anguish and of excessive toil. But suddenly as we struggled round a bend there would be a glimpse of rush walls, of peaked grass-roofs, a burst of yells, a whirl of black limbs, a mass of hands clapping, of feet stamping, of bodies swaying, of eyes rolling under the droop of heavy and motionless foliage. The steamer toiled along slowly on the edge of a black and incomprehensible frenzy. The prehistoric man was cursing us, praying to us, welcoming us — who could tell? We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. We could not understand because we were too far and could not remember, because we were traveling in the night of first ages, of those ages that are gone, leaving hardly a sign — and no memories.

The earth seemed unearthly. We are accustomed to look upon the shackled form of a conquered monster, but there — there you could look at a thing monstrous and free. It was unearthly and the men were …. No they were not inhuman. Well, you know that was the worst of it — this suspicion of their not being inhuman. It would come slowly to one. They howled and leaped and spun and made horrid faces, but what thrilled you, was just the thought of their humanity — like yours — the thought of your remote kinship with this wild and passionate uproar. Ugly. Yes, it was ugly enough, but if you were man enough you would admit to yourself that there was in you just the faintest trace of a response to the terrible frankness of that noise, a dim suspicion of there being a meaning in it which you — you so remote from the night of first ages — could comprehend.

Marlow, as Achebe observes, has reduced Africans to a racist metaphor, sorrowfully concluding that Europeans are no better than barbaric Congolese.

Important though Achebe’s essay is, Things Fall Apart (1958) provides an even more compelling refutation. That’s because, once one has experienced the richness and diversity to be found in the author’s depiction of Nigerian village life, one no longer tolerates racist caricatures. If literature’s greatest strength is capturing humanity in its full complexity, then Conrad’s work falls short in this regard.

Conrad is strongest at capturing Europe’s own heart of darkness. He arrived at his insights from witnessing King Leopold’s horrific colonialism, and the 20th century would confirm his vision time and again. America had a Conradian revelation of its own when, after believing with Obama that we had reached a new stage of enlightenment, we discovered the old prejudices were alive and well.

Unlike the European women who appear in Heart of Darkness, Trump doesn’t even pretend to hold enlightened Christian values. He’s like the rapacious ivory seekers that Marlow compares to pilgrims:

They wandered here and there with their absurd long staves in their hands, like a lot of faithless pilgrims bewitched inside a rotten fence. The word “ivory” rang in the air, was whispered, was sighed. You would think they were praying to it. A taint of imbecile rapacity blew through it all, like a whiff from some corpse. By Jove! I’ve never seen anything so unreal in my life.

Meanwhile, with his military threats and his orders for governors to “dominate” their streets, Trump also reminds me of the colonial official who has a Congolese man beaten for a fire that breaks out:

Black figures strolled about listlessly, pouring water on the glow, whence proceeded a sound of hissing; steam ascended in the moonlight, the beaten nigger groaned somewhere. “What a row the brute makes!” said the indefatigable man with the mustaches, appearing near us. ‘Serve him right. Transgression—punishment—bang! Pitiless, pitiless. That’s the only way. This will prevent all conflagrations for the future.”

In the novella, Kurtz is appalled when, on his deathbed, he looks back over his time in Africa, sees how far he has fallen from his ideals, and exclaims, “The horror! The horror!” Marlow is impressed with this final self-judgment.

One can’t imagine Trump delivering such a self-verdict, and the same increasingly seems to be true of his Republican enablers, who refuse to lift a finger each time he trashes another cherished ideal. Were he to start putting his enemies’ heads on stakes, I imagine Maine Senator Susan Collins doing no more than wrinkling her brow and expressing concern.

But back to Trump and the protesters: I think (and pray) that he’s going to have a harder time establishing himself as “the law and order candidate” than Nixon did. Most people are seeing him as the lawless one, not the protesters, most of whom are peaceful. He may find that the 1968 political playbook doesn’t work as well this time around.

If such proves to be the case, Achebe will have played a role in that.

Follow-up note: I see, from a recent New York Times interview, that the remarkable Michael Eric Dyson–academic, preacher, radio host, and cultural commentator–would remove Heart of Darkness from the canon (“it’s done so much damage in fashioning savage notions of Africa”) and replace it with Octavia Butler’s Kindred. I’ve sung the praises of Kindred multiple times (for instance, here) but, for the reasons stated above, would demote rather than entirely remove Heart of Darkness. It gets at the corrupt soul of white colonialism, even if gets Africa wrong.

I see that Dyson also admires philosopher Martha Nussbaum, who after Percy Shelley is my own favorite literary theorist). I also applaud his naming Milkman Dead from Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon as his favorite literary hero and Iago as his favorite villain. (No one in Shakespeare is worse, in my opinion.) I’m intrigued that he chooses the enigmatic Reinhart–an elusive figure from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man who assumes many masks–as his favorite anti-hero.