Before I entirely leave last semester behind, I want to look back at some of the essays I received in my “Couples Comedy in the British Restoration and 18th Century” class. Especially I want to share what my students made of Fanny Burney’s Evelina. Issues of parental separation proved paramount.

Evelina is a “coming of age” novel about an 18-year-old whose mother dies giving birth to her after being abandoned by a nobleman who pretends that their secret marriage never happened. Thus Evelina is regarded as illegitimate and her marriage prospects are dim. A friend of her grandfather, the Rev. Villars, has raised her in a modest and protected environment, but she wants to see London. He allows her to go with a friend’s family, and while in the city she experiences all the sights and sounds, including a number of predatory men drawn to her beauty. She manages to attract someone worthy, however, and not only is he a lord but her own noble father acknowledges that she is his daughter so the novel ends with a brilliant marriage.

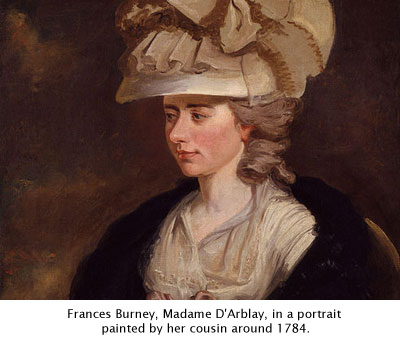

Fanny Burney was 26 when she wrote the novel and it was the hit of the season. This was in large part because it spoke directly to the concerns of young people, especially young women. I instructed my class to view Evelina and our other novels through the following writing prompt:

In Before Novels, J. Paul Hunter talks about the urgency with which young men and women of the 18th century came to novels, drawn to protagonists who were their age and facing similar life dilemmas. Choose a complex relationship dilemma encountered by one of the protagonists in Tom Jones, Evelina, or Sense and Sensibility and track the hero and/or heroine as they grapple with the different aspects of that dilemma. Think of parallel situations today for perspective.

All three of the students who wrote on Evelina looked at her relationship with Rev. Villars. As Daisy saw it, the man who raises Evelina is kind and well meaning but doesn’t really get what it is to be a young woman. He wants Evelina to be safe and thinks the best way to keep her so is by limiting her expectations. That’s why he’s initially reluctant to have her visit London. Evelina, however, hungers for experience. While she’s appropriately deferential to Villars—otherwise she couldn’t be an 18th century heroine—you can tell she’s straining at the leash.

It must have been particularly satisfying for young 18th century readers that she’s right more often than he is. Ultimately she reads the hero correctly despite Villars’ warnings.

Listening to Daisy reminded me of an observation I’ve developed after 30 years of teaching young people. It goes something like this: Parents and young adults are following two different programs. Parents are programmed to keep their children safe and so think in terms of practical majors that will lead to immediate jobs that will cover rent, health insurance, and debt payments. Their sons and daughters are programmed to experience the world in all its diversity. A fair number of intense arguments emerge from these conflicting perspectives.

With that in mind, there was another student who wrote a very tangled essay about Evelina (not all essays I receive are successful, even after revision). But the very shortcomings of the essay were illuminating. Drawing on his own experience of wanting to attend the University of Maryland but his parents making him attend the “safer” St. Mary’s College, he found himself caught between praising Evelina for venturing out in the world and praising Villars for trying to protect her. As you can imagine, his handling of Villars was a bit of a mess. But at least literature had set him up to begin outlining the tensions in his own life.

A third student, Erika, looked at Evelina’s dilemmas from a slightly different angle, noting how her lack of a support structure makes her vulnerable to men who want to humiliate her or worse. While the family she is with takes care of their own daughter, Evelina finds herself pretty much on her own. She doesn’t have anyone who teaches her the etiquette needed at dances and she doesn’t have a chaperone who will protect her from rakes. She has to get out of difficulties on her own.

Erika said that his was pretty much been her own situation during her high school and college years.

But Erika did note one important resource that Evelina has: Villars has given her an inner compass that she uses at certain critical moments. Erica realized that she did as well and came to appreciate her own upbringing as she wrote about the issue.

Great novels, in other words, are always timely.