Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. I’ll subscribe you via Mailchimp for the weekly or email you directly for the daily (your choice). Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone.

Wednesday

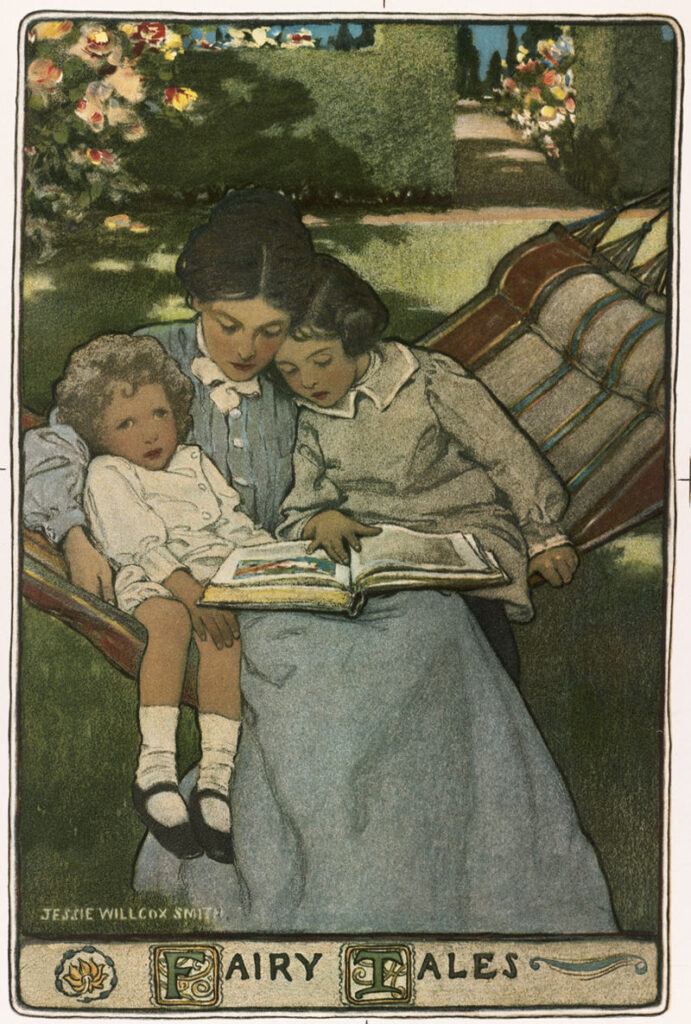

Yesterday I wrote of how A.S. Byatt’s novel about artist communities in late Victorian and Edwardian England has taken me back to my own childhood. From the moment we could understand “chapter books,” my father read my brothers and me novels from that period, and they have shaped the way that I see the world.

Byatt observes that children’s lit flourished because people were coming to see children in a new way:

The Fabians and social scientists, writers and teachers saw, in a way earlier generations had not, that children were people, with identities and desires and intelligences. They saw that they were neither dolls, nor toys, nor miniature adults. They saw, many of them, that children needed freedom, needed not only to learn, and be good, but to play and be wild

Byatt notes that many of them saw this “out of a desire of their own for a perpetual childhood.” She then turns to some of these works:

In 1901 James Barrie wrote The Boy Castaways for the Llewelyn-Davies boys, Peter Rabbit was published, and Kipling published Kim, the tale of a boy scout. In 1902 E. Nesbit wrote Five Children and It, a tale where resourceful, unwise children meet a sand-fairy. In that year Barrie published the Little White Bird, in which an embryonic Peter Pan, the little boy who wouldn’t grow up, made his first appearance. [It] was staged (in a primitive form) in 1904. Rupert Brooke went to see it twelve times. In 1906 [Kipling’s] Puck of Pook’s Hill appeared, and so did The Railway Children and Benjamin Bunny. It was seriously suggested that the great writing of the time was writing for children, which was also ready by grown-ups.

Byatt also mentions Kenneth Grahame, who balanced working as a high-level bank secretary with writing The Golden Age, Dream Days, and The Wind in the Willows (1908).

We don’t only see children’s literature in Byatt’s novel. In an Edenic scene, we watch as the children, now adolescents, gather to camp out, swim, and converse. Among their topics of conversation is literature:

They read plays—[John Milton’s] Comus, with Griselda as the Lady, Julian as Comus and Gerry as the Attendant Spirit, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with Wolfgang as Oberon, Florence as Titania, Imogen as Hippolyta and Charles, Griselda, Dorothy and Geraint as the confused lovers. Tom was Puck. Toby Youlgreave read Sir Philip Sidney and Malory, Joachim Susskind and the Sterns read poems by Schiller and Goethe, Julia read Marvell’s “Garden” and Tom read Tennyson. Julian had learned conversations with Toby Youlgreave about Philip Sidney.

The discussion about the Elizabethan poet Sidney leads to an insight into how what we read can transform what we see. The passage is from Sidney’s Defence of Poesy:

Sidney had written what Julian believed was his favorite sentence—certainly his favorite this year. “Nature never set forth the earth in so rich tapestry, as divers Poets have done, neither with pleasant rivers fruitful trees, sweet-smelling flowers: nor whatever else may make the too much loved earth more lovely. Her world is brazen, the Poets only deliver a golden…”

From this experience Julian, a student at Oxford, determines to study the pastoral form:

He said he had been looking for a thesis subject, in case he decided to apply for a Fellowship at King’s, and he rather thought there might be something there. “English pastoral, in poetry and painting—” Pastoral was always at another time, in another place. Even the green pool and the long walk, over the Downs, would not become pastoral until they were past. And yet, the sun shone on them, and the leaves and the water and the grass shone with its reflections.

If we sometimes look back at the Edwardians with pastoral nostalgia, it’s because World War I blasted it utterly, flinging us violently into “the Age of Lead.” Rupert Brooke, of “If I should die, think only this of me,” would die in that war, as would many fellow poets and artists.

To be sure, the ending of childhood is often traumatic. It’s just that the break is not normally so violent.