The focus in this week’s posts is on Supreme Court justices and literature. I notice that, in his New York Times column today, moderate conservative David Brooks endorses Sonia Sotomayor for just that restrained balance that we discussed yesterday as we explored her early love for Nancy Drew novels. Today I’m going to talk about a justice who, in college, was drawn to far angrier novels. (I can’t speak to what Sotomayor was reading in college.) Reportedly, Justice Clarence Thomas cites as influences Richard Wright’s Native Son and Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead.

I know only a little about Thomas’s life and his Supreme Court opinions, but many have pointed out a key contradiction in his life: that he benefitted from affirmative action programs and is now a vocal critic of affirmative action. Born in 1948 and raised in the segregated south (first in rural Georgia and then, after his house burned down, in Savannah), he attended the College of the Holy Cross and then Yale University Law School. He served in the Reagan administration and was chosen by the first George Bush for the Supreme Court to replace Thurgood Marshall because he was seen as one of the few black candidates who would deliver reliable conservative rulings. He has met if not exceeded these expectations.

While Sonia Sotomayor appears grateful to affirmative action programs that supported her (as does Barack Obama), Thomas feels diminished by them. His anger appears to be directed more at white liberals who accepted him only as a token black than at white conservatives who would have banned him altogether—conservatives like, say, Yale law professor Ralph K. Winter who, according to Salon, was quoted (while Thomas was at Yale) as complaining that none of Yale’s minority students were truly qualified to be there.

Think about the conflicted feelings that such statements would have given rise to in Thomas. Here is a man who, affirmative action or not, has accomplished a tremendous amount, and yet who feels dismissed at every turn. I can imagine him wanting desperately to be accepted on his merits as an individual and feeling that, perhaps, conservatives (even racists) are better at talking about merit than liberals. Given that the left can sometimes sound patronizing and mushy, better to go with the right.

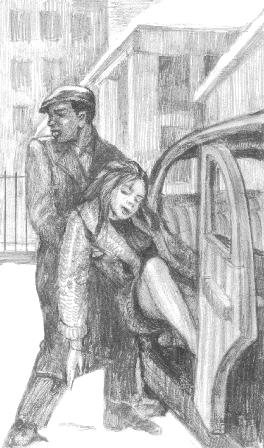

Richard Wright’s magnificent novel must have been balm to Clarence Thomas’s wounded sensibilities. It is one of the angriest novels that I know, telling the story of Bigger Thomas, an angry black man raised in rat-infested tenements who suddenly finds himself working for white liberals. When he accidentally suffocates the daughter, he begins to carve out an identity for himself. A white communist, the woman’s boyfriend, ends up befriending him and learns to go beyond political stereotypes to appreciate Bigger and his anger. In the end Bigger is condemned to be electrocuted by a judge who cannot hear the mitigating circumstances of racial oppression that have conspired to define him.

There was an interesting debate about the novel that Clarence Thomas might have encountered when he was in college. James Baldwin, who owes a lot to Richard Wright, nevertheless had problems with Native Son, and in the 1948 essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel” he criticized Native Son as a protest novel that didn’t allow room for dialogue between whites and blacks. In 1968, when Thomas was at Holy Cross, black militant (and serial rapist) Eldridge Cleaver attacked Baldwin for his criticism, arguing in Soul on Ice that Bigger’s rage was a legitimate response to white oppression and that Badwin just wanted to be “fucked up the ass by a white man” in his desire for interracial dialogue.

I tell this story here to get at just how charged Wright’s book is.I actually don’t think that either Baldwin or Cleaver is doing justice to it because I think Wright’s book is more nuanced than either of them admit.Wright captures the limitations as well as the strength of Bigger’s anger, and he depicts white understanding along with white insensitivity. Baldwin’s response I can understand because, in trying to carve out a space for his own lower octane fiction, he feels he needs to distance himself from his brilliant predecessor.But the relevant point here is that Wright gave voice to a black anger that wasn’t acknowledged, either in 1940 or for several decades later.Thomas must have felt that someone finally understood his own anger, an anger that, growing up in the south and then attending mostly white schools, he would have had to keep buried.He must also have recognized, in the book’s white liberals, the patronizing responses he encountered.What he doesn’t seem to have responded to is the vision (embodied in the communist character Jan) that whites can grow in understanding.

Instead he turned to the novels of Ayn Rand, most notably The Fountainhead. I’ll save the bulk of my reservations about Ayn Rand for another day (I believe she has seriously misled numerous readers, even though there is some truth in her vision). I will just note, as part of my narrative thread here, that she is the ultimate proponent of the self-made individual, the Nietzschean superman, who lives by his own rules. He has to, in her mind, if he is to follow his revolutionary vision because the mediocre masses, with the weapons of society at their disposal, are bent on dragging down to their level anyone who tries to stand out.

Rand appeals to people who feel that they are alone and that their gifts are not appreciated. She is a favorite of certain angry libertarians. What Clarence Thomas finds in her, I suspect, is similar to what he finds in Richard Wright, even though Rand was a fervent anti-communist while Wright was a one-time member of the communist party. Both rage against the machine, which they feel fails to acknowledge the inner life of the individual.

Clarence Thomas has gone on to find a kind of acceptance in the conservative community, even as many in the black community feel that he has turned his back on them. Perhaps this vision of the isolated and misunderstood individual helps support him in the midst of all the criticism he receives. Maybe it also makes him much more prepared to make more radical court decisions than say, Sotomayor would. According the Ken Foskett biography on Thomas, Justice Scalia sees Thomas as even more willing than he is to overturn a constitutional line of authority—stare decisis—if he thinks it is wrong. (Some believe that Thomas has influenced Scalia more than Scalia has influenced Thomas.) If Nancy Drew captures Sotomayor’s inclination to work within the system to change things, Wright and Rand capture Thomas’s openness to sharp breaks with rule and precedent and his readiness to rule in favor of those individuals and corporations that challenge the social welfare state.

5 Trackbacks

[…] encounter with overt black anger and I was thoroughly unsettled. When I learned that this was an important college book for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, I came to understand him a bit better (even though I still disagree with most of his […]

[…] about books that were meaningful for justices Sonia Sotomayor and Clarence Thomas (Nancy Drew and Native Son respectively). Sotomayor has proved to be outspoken, direct and unafraid, like Nancy, and […]

[…] out as favorites, and while I’ve done so several times (with Obama, Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, Clarence Thomas, Jared Lee Loughner, Anders Breivik, and American presidents in general), I’m always careful to […]

[…] see what insights we can gain. (See previous posts on Barack Obama, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Clarence Thomas, and a range of presidents.) I was therefore interested when Mitt Romney mentioned Ron […]

[…] fascinated me: why is Native Son one of conservative Justice Clarence Thomas’s favorite books. I’ve written about this in the past but have now achieved new […]