Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Wednesday

Yesterday’s Washington Post reminded us of a horrific lynching that occurred in Jasper, Texas 25 years ago, along with a follow-up report on what has occurred there since. The hate crime led to a Lucille Clifton poem, which I heard her read not long after she composed it.

Post reporter Emmanuel Felton tells what happened:

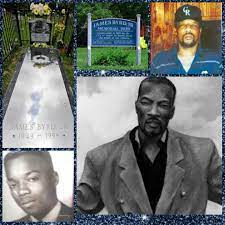

On a June evening in 1998, three White men chained a Black man by his ankles to the back of a pickup truck and dragged him for several miles down a twisting country road in this small East Texas town, decapitating him in the process. The next day, pieces of James Byrd’s body were found all along the route.

Clifton is often an inspirational poet, finding ways to triumph in the most desperate of circumstances. (I think of how she uses poetry to process her father abusing her as a child.) In “jasper texas 1998,” however, she is just discouraged, writing, “Hope bleeds slowly from my mouth/ into the dirt that covers us all.”

In the poem, Clifton imagines herself as Byrd’s head, speaking for his dismembered body. While his body is no longer recognizably human, the truly disfigured are the ones whom racism has twisted. “Who is the human in this place,” the speaker asks, “the thing that is dragged or the dragger?”

At such moments, bridging the racial divide seems an impossible task. “why and why and why/ should i call a white man brother?” Clifton asks through Byrd. In her current state, there seems no reason to do so, even though Jasper’s Black and White citizens—at least some of them—have come together to sing “We Shall Overcome.” Here’s the poem:

jasper texas 1998

By Lucille Clifton

for j. byrd

i am a man’s head hunched in the road.

i was chosen to speak by the members

of my body. the arm as it pulled away

pointed toward me, the hand opened once

and was gone.

why and why and why

should i call a white man brother?

who is the human in this place,

the thing that is dragged or the dragger?

what does my daughter say?

the sun is a blister overhead.

if i were alive i could not bear it.

the townsfolk sing we shall overcome

while hope bleeds slowly from my mouth

into the dirt that covers us all.

i am done with this dust. i am done.

Sadly, the Washington Post story shows the poem to be predictive, with current day Jasper focused on forgetting the incident:

But now, 25 years later, the horrific attack that once galvanized this community is barely discussed. Byrd is not mentioned in the local school district’s Texas history textbooks and he’s absent from the Jasper County Historical Museum, which opened in 2008. His family says their efforts to keep Byrd’s memory alive, including a push to open a museum in his honor, have largely been met with lackluster support from local officials. Few people showed up at a Juneteenth event they held this year to acknowledge the anniversary of Byrd’s murder.

It’s as though Jasper wants the dust to be swept under the rug. As reporter Felton observes,

The town’s collective amnesia reflects the worst fears of racial justice advocates about what may follow George Floyd’s 2020 murder by a Minneapolis police officer. Byrd’s death, like Floyd’s, was supposed to represent a turning point in American history, but it has been relegated to a footnote even in his hometown, they say.

No wonder Clifton sounds so discouraged. If things like this keep on happening, then the only true equality we can hope for is one day becoming indistinguishable dust. “We therefore commit this body to the ground, earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust,” reads the Anglican burial service.

And if that’s the case, then one can understand why even a fighter like Clifton would say, “i am done with this dust. i am done.” Along with the dust through which Byrd has been dragged, Clifton could also be talking about humanity. As in, “I’m fed up with people!”

Even as the poem captures the poet at her most discouraged, however, her composing it is itself a refusal to fully surrender. To be sure, poetry, as truth, has to give full weight to those moments when we are down and despairing; we can’t just skip over them. But having acknowledged this, we must also acknowledge that African Americans, despite all that they have suffered, have refused to stay buried by dust for long.

For instance, writing about her revelation (this at her father’s funeral) that there is hope even after one has been sexually abused, Clifton proclaims,

only then did i know that to live

in the world all that i needed was

some small light and know that indeed

i would rise again and rise again to dance.

While Byrd can’t rise again from the dust—his tragedy should remain with us always—the rest of us can keep fighting, keep dancing, to create a world where Jasper, Texas doesn’t keep happening. Hope and realism must combine forces.