Friday

I felt like a proud father last week when a former student, now Dr. Molly Robey at Illinois Wesleyan University, returned to St. Mary’s to speak about “Transdomesticity: (Inter)Sex and the College Girl, 1870-1890.” Among other things, Molly showed me that the obsession of North Carolina Republicans over transsexuals is nothing new. The figure of “the College Girl” stretched people’s conceptions of sex and gender in late 19th century novels.

I felt like a proud father last week when a former student, now Dr. Molly Robey at Illinois Wesleyan University, returned to St. Mary’s to speak about “Transdomesticity: (Inter)Sex and the College Girl, 1870-1890.” Among other things, Molly showed me that the obsession of North Carolina Republicans over transsexuals is nothing new. The figure of “the College Girl” stretched people’s conceptions of sex and gender in late 19th century novels.

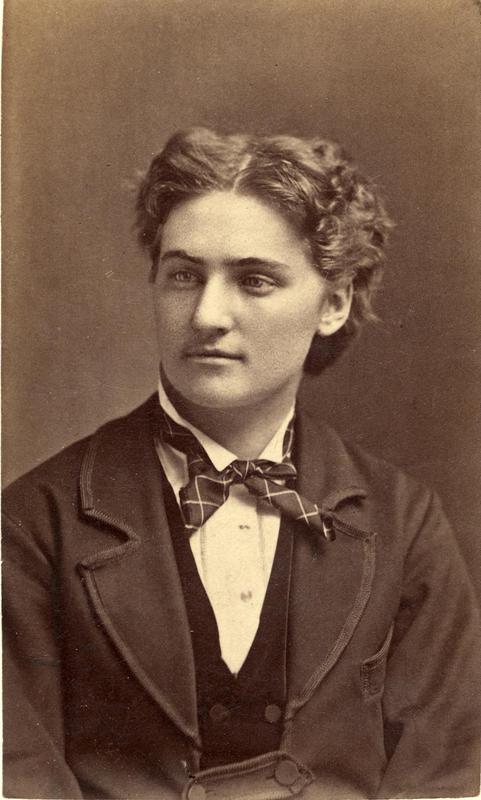

Apparently there were college novels at the time in which female protagonists refused to conform to the ideals of “Victorian True Womanhood,” which included piety, purity, submission, and domesticity. One of these was SOLA’s An American Girl and Her Four Years in a Boys College. SOLA was a protective acronym for Olive San Louie Anderson.

SOLA was one of the first women students to graduate from the University of Michigan and her novel is based on her experience there. The protagonist, Wilhelmine “Will” Elliot, confuses her classmates. As Molly observed, Will

is frequently described as “queer” and “boyish” by her peers, who feel uncomfortable with the ways that Will’s appearance, manner, and behavior violate their expectations of femininity. As her classmates see it, Will is not exactly a woman nor exactly a man. Her dearest friend Nellie describes Will as “the most delightful mixture of boy and girl that I ever met.” Her critics call her “the Queen of the Amazons,” and one of her classmates, Guilford Randolph (to whom she later becomes engaged), says of her, “I can’t bear her style . . . . why, I’m afraid of her: she is brilliant and all that, but so cold and sarcastic and independent, and then she has such a way of aping boys; her very name is boyish—‘Will’ . . . . Then her hats are always the same boyish style. . . . She is the first girl that I can’t understand.” It is this lack of understanding, this inability to categorize Will, that inspires insecurity in the people around her. Randolph handles this anxiety by relegating Will to the category of nonhuman; in violating the boundaries of gender, Will “apes” the boys. What Randolph’s comments reveal here is that his conception of what is human is deeply tied to his belief that male and female are natural categories. Eventually, Will herself becomes confused about her gender identity, and she questions why she has to be so “odd.”

Molly talked about different scientific theories about educated women at the time. Dr. Edward Clarke, a noted Boston physician and former professor of medicine at Harvard, authored Sex and Education (1873), which

examines the effects of education on women’s physiology. His basic argument is that education will unsex women, creating a third, intermediate sex, which he calls the “Agene.” Dr. Clarke argues that at the crucial stage of reproductive development—the time when women would be attending college—women need to have their energy directed toward the development of their ovaries, not their minds. For girls who engage in vigorous study at this period, the reproductive system will never fully develop. The consequences of such action include poor breast milk production, decreased fertility, and, in many cases, sterility.

Those arguing in favor women in higher education often weren’t much better, Molly noted. Take, for instance, Vassar’s first president John Raymond, who argued in 1870 that higher education makes a woman “more of a woman”:

By as much as she has felt the true effect of her studies, she must forever after be—not more like a man, but more of a woman, and more what a woman ought to be, wherever she moves or whatever she may be called to do. In the family circle, in the church, and in all the relations of society, she will fill a larger space and be felt as a greater power. . . . She will be a fit companion for a wiser and nobler man, than she otherwise would have been. . . . and if she becomes a mother, she will draw on larger resources for the instruction and training of her children.

While Molly obviously doesn’t buy either man’s views, she was intrigued by Clarke’s theory that college was turning women into a third gender, neither male or female. In that way, even though disapprovingly, he pointed to an identity beyond a strict male-female binary. Many transsexuals today argue for a version of this.

As Molly sees it, the college novel functioned as a kind of fantasy space in which authors could explore gender and sexual identity. Although college novels sometimes ended by reinscribing traditional roles (but not always), readers had the opportunity to imagine other possibilities as they read them.

One other idea: Molly pointed out that the very word “girl” was less fixed in the 19th century than it is today.

I would like to suggest that the term “girl” may not be as self-evident as we imagine. In our current moment, “girl” has a very specifically gendered meaning. I don’t have to look much farther than my own four-year-old daughter to see that. Already she has a deeply-ingrained sense that she should love pink, wear dresses, and aspire to be a princess despite my own best efforts. But the meaning of “girl” in the 1870s was not so set. To be a “girl” meant that one was in an in-between or liminal stage. Girlhood was a process of becoming, a space of passage not a place of arrival. A “girl” in the nineteenth-century was unformed, not yet subject to many formal and informal modes of regulating gender. Girls were allowed to be physical. Girls were allowed to attend school. Really, the nineteenth-century conception of girlhood is not so different from how transgenderism has been conceived, at least by some scholars. These scholars write that transgenderism should not be understood as one fantasy of male or female embodiment, but should be seen as a multiplicity of “masculine” and feminine “bodily expressions and feelings.”

As I listened to Molly’s talk, I remembered the immense comfort I found as a young boy in novels that leaned the other way—which is to say, works that had boy protagonists with girl characteristics, like Francis Hodgson Burnett’s Little Lord Fauntleroy and L. Frank Baum’s The Land of Oz (where Pip discovers that he is actually the enchanted girl ruler Ozma).

For young people who feel that some cosmic mistake has been made in their anatomical gender, books like American Girl appear as a life raft. The narratives assure them that someone out there understands them.