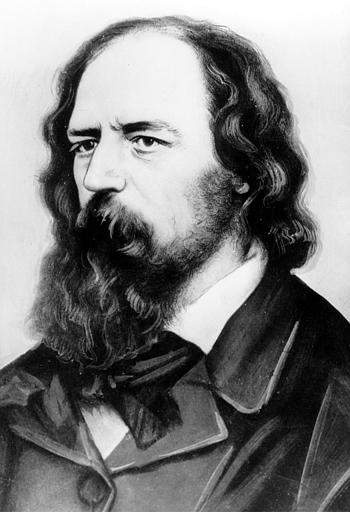

Alfred Lord Tennyson

In spending the last two weeks discussing how poetry can come to our aid in a season of death, I have been exploring how poetry responds to its greatest test. Death and dying can trigger our deepest fears, generate panic, denial and anger, prompt us to question everything we believe in, and send on frantic quests for meaning. Can literature step up to the plate on such occasions? We will dismiss it as so much bullshit if it offers us only vapid comfort or insubstantial reassurance.

Poetry, of course, cannot keep death from happening. I have been arguing that there are poems, however, that can help us step beyond the fear and anger into a different relationship with death.

Think about how remarkable a feat that is. Death and dying, after all, challenge language to its limits. We all know acutely how difficult it is for words to rise to the occasion when someone is dying or has lost or is losing someone close. As I mentioned in an earlier entry, after my son died I witnessed people avoiding me because (I assumed) they were worried that they didn’t have an adequate verbal response.

Tennyson writes about the inadequacy of his words in In Memoriam, his great poem about his very dear and brilliant friend Arthur Henry Hallam, who died of a sudden brain hemorrhage at 22. Tennyson writes:

I sometimes hold it half a sin

To put in words the grief I feel;

For words, like Nature, half reveal

And half conceal the Soul within.

I will write more about Tennyson’s poem in future entries because no poem has been more powerful in helping me process my son’s death than this one. For the moment, however, I just want to focus on the issue of how much language can do.

After saying that language can only half reveal—in fact, it even half conceals—the grief it attempts to express, Tennyson then goes on to talk about why he resorts to it anyway. One reason, he says, is that the very act of writing poetry helps numb the pain. As does, I would add, the act of reading it:

But, for the unquiet heart and brain,

A use in measured language lies;

The sad mechanic exercise,

Like dull narcotics, numbing pain.

Therefore, Tennyson says, he’ll continue to write about his sorrow, even though he knows that a poem can give only rough outline to grief, nothing more.

In words, like weeds, I’ll wrap me o’er,

Like coarsest clothes against the cold:

But that large grief which these enfold

Is given in outline and no more.

One strategy that Tennyson uses to capture his grief in these lines is to talk about how impossible it is to capture grief. It is as though, by gesturing towards that which cannot be adequately described, he comes closer to approaching it. In so doing, he gives a sense of how poetry works and why poetry does a better job than any other use of language in getting at death. Poetry is language working overtime, words used with maximum effect. In poetry’s compression, more meaning can be hinted at or alluded to than when we try to express ourselves more directly. That’s why people give poetry in times of death. And also, for that matter, why they write and give poetry when they are in love, another great imponderable.

How about other forms of literature, such as the novel? I plan to write a future entry on Gail Godwin’s The Good Husband, a powerful novel about a woman dying of cancer which helped me deal with my friend’s cancer. At the moment, I will just say that, while I normally prefer novels to poetry—I am much more familiar with contemporary fiction than I am with contemporary poetry—poetry was what I needed when I was wrestling with Justin’s death. Only poetry, it seemed to me, had the spiritual gravitas to speak to my pain.

One Trackback

[…] posts I have written on In Memoriam can be found here, here, here, here, and here. This entry was posted in Bates (Julia), Tennyson (Alfred Lord) and […]