Today I share another of this year’s senior projects. (Monday I reported on a Kurt Vonnegut project.) Sydney Coleman, a wonderfully gracious and smart African American student, is exploring the theme of bad girls in gothic literature—or to be more exact, gothic novels that exhibit a complicated relationship between good girls and bad girls.

Sydney hasn’t entirely narrowed down her project and is contemplating on taking it in one of two directions. One possibility is focusing only on women and examining Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, Margaret Atwood’s Robber Bride and Alias Grace, and Toni Morrison’s Sula. While Sula isn’t strictly speaking a gothic, Morrison has taken the gothic convention of the femme fatale and reinscribed it in the African village witch tradition.

But Sydney also finds herself fascinated by Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and might choose instead to look at gothic treatments of bad boys as well as bad girls. In that case, she would focus on novels that are either written during Victorian times (Dr. Jekyll, Jane Eyre) or set in the period (Alias Grace). Atwood’s novel takes place in 19th century Canada and has a Jekyll-like protagonist, the civilized and humane Dr. Simon Jordan. Jordan is riveted by Grace Marks, a bloody murderess who comes across as an “angel in the house” (to cite the phrase from Coventry Patmore’s famous 19th century idealization of women).

Sydney hasn’t had to make up her mind yet as she is still writing on Jane Eyre and Alias Grace.

To explore these works, Sydney is relying on Carl Jung’s concept of the shadow figure or doppelganger and Freud’s concept of the uncanny. The gothic form, she is discovering, allows authors to explore the uncanny, which is to say, the uncomfortable strangeness that we feel when we encounter a side of ourselves that we don’t like to acknowledge but that we nevertheless recognize. In Freud’s formulation, when we deny the recognition, repressing it by pushing it into our subconcious, it becomes pathological. Freud calls this acting out “the return of the repressed.”

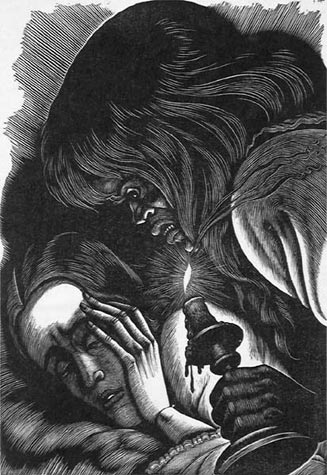

To cite an instance of the uncanny in Jane Eyre, when Jane is restlessly pacing through the gothic mansion Thornfield Hall, she sometimes hears the eerie laughter of a madwoman in the attic:

When thus alone, I not unfrequently heard Grace Poole’s laugh: the same peal, the same low, slow ha! ha! which, when first heard, had thrilled me: I heard, too, her eccentric murmurs, stranger than her laugh. There were days when she was quite silent; but there were others when I could not account for the sounds she made.

Though from a plot point of view this madwoman is actually Bertha Mason, psychologically it is the disturbed part of Jane’s own mind. The house is a metaphor for Jane’s self and Bertha is her shadow side. The uncanny aura of the scene signals the uneasy identification she has with those passions that she has repressed because society deems them unacceptable in a woman.

Alias Grace too has such doubling. When she commits her murder, Grace appears to be possessed by Mary Whitney, a former roommate who is raped by her employer and then dies following a botched abortion. This vengeful Mary surfaces when Grace murders her own employer and, later, when Grace undergoes hypnosis. At all other times Grace appears gentle and upright.

Dr. Jordan can’t explain why he is so drawn to Grace while remaining uninterested in the “nice girls” that he encounters. One of these nice girls, significantly, is also fascinated by Grace and has a scrapbook containing all the newspaper accounts of the murder and trial.

My student is a nice girl—super nice, actually—and I sometimes joke with her that she is trying to figure out whether she herself has a shadow side. Actually, it’s not a joke since I know that we all have shadow sides. I am looking forward to what Sydney will discover about herself as well as about the works she has chosen.