Monday

My wife Julia alerted me to an intriguing although somewhat frustrating article in Atlantic about the end of time. Drawing on Frank Kermode’s 1967 The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction, Megan Garber wrestles with an issue recently raised by The Washington Post: how do we live with constant reminders that the earth is in trouble? Normally, we think of the apocalypse as being in the future, but what if it is going on now, only we aren’t facing up to it? If that’s the case, Garber says, we need a new kind of narrative to handle it.

At first glance, we would appear to have such a narrative in post-apocalyptic fiction, where everything from environmental devastation to zombies threatens our future. But what if the future is both less dramatic and already underway?

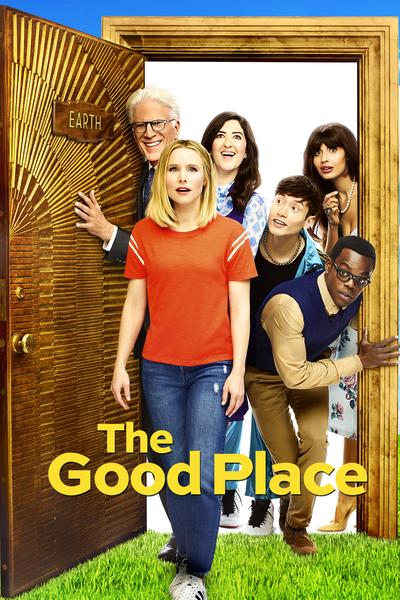

To make her point, Garber spends a fair amount of time talking about The Good Place and Forever, two shows about people living in the afterlife. They have already experienced their own personal apocalypses (death), and now are figuring out how to deal with it.

These television shows are taking on the task that Kermode assigns to fiction generally, which is to provide structure that will help us understand life, which has no structure. In this process, literary endings play a particularly important role. We look at how a work concludes to figure out the meaning of what comes before.

A happy ending might affirm that virtue is ultimately rewarded and justice will prevail. A tragic ending, on the other hand, might signal that, while society doesn’t understand the protagonist’s worth, higher values are legitimated because they can be seen by the reader. Ironic, absurd, and open endings each point to their own range of meanings.

Whatever the case, endings provide us with a vantage point, sometimes after the worst has happened, to take reality’s measure. That explains Garber’s comment that there is an apocalyptic dimension to literary endings.

For his exploration, Kermode turns to Dante, Blake, and T S. Eliot (in The Wasteland), all of whom grapple with the meaning of end times. Yeats famously does as well in “The Second Coming,” which asserts that the world is falling apart (“the center cannot hold”) and predicts that some rough beast, “its hour come round at last,” will slouch toward Bethlehem to be born.

In all these literary formulations, however, the future is in the future. But what if the future is now?

Garber mentions one interchange between June and Oscar in Forever that shows that meaning might not be revealed by such an ending:

“So we just keep … going?” June wonders, incredulously. “I mean, how long does this go on for? I mean, what’s the point of all this?”

Oscar’s reply is both searing and blunt: “Well, what was the point of the thing before this?”

Garber asserts that, in Happy Place and Forever, narrative loses some of its tragic potential and becomes world-weary surrender. Or as she puts it, “The end is nigh, and also the end is … sigh.” She elaborates:

The contemporary sense of an ending takes its form not as the dramatic fulfillment of an ancient prophecy—“Surely some revelation is at hand; Surely the Second Coming is at hand”—but rather as a tangle of dull and daily inevitabilities. Warming waters. Whipping winds. Things falling apart. The leader, careless and cruel, refusing to see what is plain. If every age has its version of apocalypse, the soft tragedy of our own is that it can no longer be safely situated in the future. Our end-times, instead, lurk among us, furtive and fierce and all too present-tensed, waiting, watching, lingering, biding—understanding, far better than we allow ourselves to, how little it takes to turn the good place into the bad.

When Garber puts it this way, however, she makes a point not unlike the conclusion of T. S. Eliot’s “Hollow Men”: “This is the way the world ends, not with a bang but a whimper.” Thanks to climate change science, we may have more factual basis than Eliot and Yeats did to declare the end is nigh, but their sense of exhaustion and hopelessness is hardly new. Many great works throughout the ages have had this for a theme. Alexander Pope in the 18th century (The Dunciad), Matthew Arnold in the 19th (“Dover Beach”), and Samuel Beckett in the 20th (Waiting for Godot) all immediately come to mind.

That’s because, no matter how bad things get, we’re still alive, which means the worst hasn’t happened yet. Shakespeare, as always, understood this, expressing it through Edgar when he encounters his blinded father in King Lear:

Edgar: O gods! Who is’t can say ‘I am at the worst’?

I am worse than e’er I was.

[Aside] And worse I may be yet. The worst is not

So long as we can say ‘This is the worst.’

We put off the apocalypse because we can’t help but imagine being alive the following day. We don’t need new literary forms to show us that.