Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Tuesday

A few weeks ago Hullabaloo blogger Tom Sullivan wondered whether novelist Anthony Burgess has proved prescient with his novel A Clockwork Orange (1962). Are parts of America being conditioned by Russian authoritarianism?

Sullivan was responding to a Washington Post article about how “Red states Threaten Librarians with Prison,” something we couldn’t have imagined happening a few years ago. It took me a moment to understand Sullivan’s point. Then I recalled my own experience reading Anthony Burgess’s Clockwork Orange in college.

It was as Sullivan describes: one is subtly conditioned as one reads the novel. Throughout, protagonist Alex uses a Russian-based teen slang called Nadsat, which Burgess has declined to translate. That doesn’t matter, however, as one senses what the words mean, even if one doesn’t know for sure. I still remember how, when reading the book in college, this rhetorical strategy got me to bond with the narrator Alex in unsettling ways. As Burgess observes,

The novel was to be an exercise in linguistic programming, with the exoticisms gradually clarified by context: I would resist to the limit any publisher’s demand that a glossary be provided. A glossary would disrupt the program and nullify the brainwashing.

To give you a taste of the experience, here’s Burgess’s opening:

“What’s is going to be then, eh?”

There was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs, that is Pete, Georgie, and Dim. Dim being really dim, and we sat in the Korova Milkbar making up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening, a flip dark chill winter bastard though dry. The Korova Milkbar was a milk-plus mesto, and you may, O my brothers, have forgotten what these mestos were like, things changing so skorry these days and everybody very quick to forget, newspapers not being read much neither. Well, what they sold there was milk plus something else. They had no license for selling liquor, but there was no law yet against prodding some of the new vesches which they used to put into the old moloko, so you could peet it with vellocet or synthemesc or drencrom or one of two other veshches which would give you a nice quiet horrorshow fifteen minutes admiring Bog And All His Holy Angels and Saints in your left shoe with lights bursting all over your mozg. Or you could peet milk with knives in it, as we used to say, and this would sharpen you up and make you ready for a bit of dirty twenty-to-one, and that was what we were peeting this evening I’m starting off the story with.

And here’s what Alex and his gang members—excuse me, his droogs–do for fun.

Our pockets were full of deng, so there was no real need from the point of view of crasting any more pretty polly to tolchock some old veck in an alley and viddy him swim in his blood while we counted the takings and divided by four, nor to do the ultra-violent on some shivering starry grey-haired ptitsa in a shop and go smecking off with the till’s guts. But, as they say, money isn’t everything.

After various acts of violence, including a rape that ends in murder, Alex is captured and imprisoned. Thanks to an aversion therapy process known as “the Ludovico Technique,” he transitions from nihilistic thug to conditioned lab rat who gets sick whenever he witnesses or even thinks about violence. At the end of the novel—or at least, the end of the novel as it originally appeared—the government deprograms him back to his original thug self, only this time it does so in order to exploit his thuggery for its own purposes.

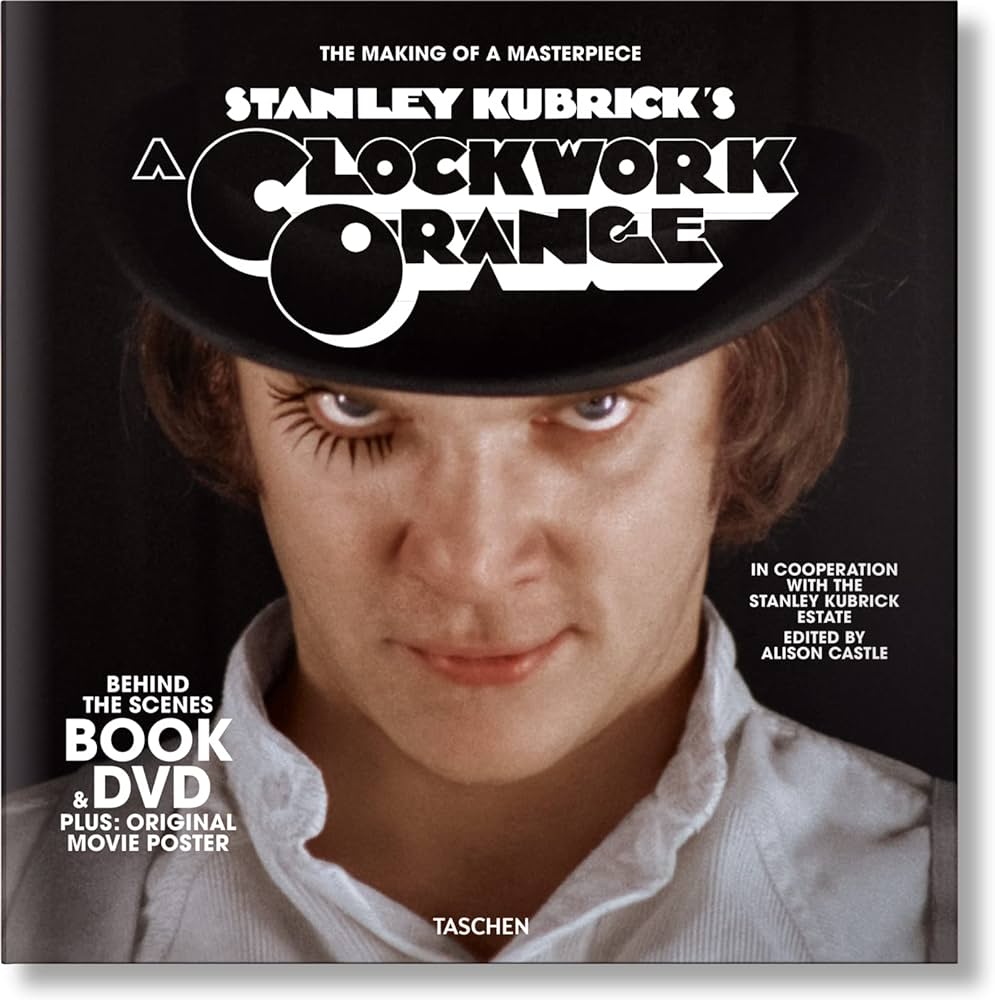

It so happens that Burgess wanted the novel to end differently and wrote a last chapter in which Alex becomes tired of his formerly violent ways and contemplates settling down and starting a family (although he predicts that his kids will be even more violent than he was). The original publisher pressured him to drop this chapter while, in his movie version, Stanley Kubrick ignored it. As a result, there’s no counter in the book or movie to what appears a celebration of “ultra-violence.”

It is because of the publisher’s decision that readers (including Kubrick) interpreted the novel as glamorizing violence. After all, Alex’s flashy rhetoric and uninhibited behavior have more vibrancy than any of the governmental institutions or civilized norms responsible for maintaining social order.

The idea of the government using thuggery for its own purposes brings to mind Donald Trump encouraging the Proud Boys and other violent groups to attack the Capitol on January 6. Meanwhile, he continues to ramp up his incendiary threats in campaign rallies, insisting that only a rigged election will keep him from winning in 2024. (In a recent New Jersey rally he even lionized Al Capone and Hannibal Lecter.) For its part, the GOP has long endorsed unregulated access to firearms and celebrated such vigilante killers as George Zimmerman, Kyle Rittenhouse, and the Arizona rancher who shot a migrant.

The two extremes we witness in the book—someone conditioned to follow orders and someone running wild in the streets—are not as contradictory as it may seem, at least when it comes to fascist logic. I think of Hitler’s Night of the Long Knives (1934), where he consolidated power by having the Gestapo extrajudicially execute his rowdier followers. (They killed 85 in the initial purge and perhaps as many as a thousand in the subsequent weeks.) I could well imagine a reelected Trump, were he to gain control over the military, using it to crack down on undisciplined groups like the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers and perhaps on Steve Bannon as well. Using Nazi Germany as a model, street stormtroopers are useful in the early stages of a fascist takeover but a liability when they alienate potential allies in the business and military communities.

In his article, Sullivan must acknowledge that, in one way, Clockwork Orange describes the opposite of what we are seeing. About the library bans, which for the most part target LGBTQ+ authors and authors of color, he writes,

The bans are a Republican reverse-Ludovico Technique aimed not at forcing children to read but Brezhnev Era censorship designed by right-thinking “patriots” hoping to prevent children’s exposure to ideas they deem wrong-thinking.

Still, conditioning young people, as Hitler did with the Nazi Youth, is a key agenda for the authoritarian right.

If we readers can be conditioned through Burgess’s use of Nadsat, we have a chance to see just how susceptible we are to manipulation. In fact, it’s a shock in the final chapter (the chapter dropped by the publisher) when we encounter one of Alex’s former droogs speaking standard English and his new wife giggling at Alex’s use of the old lingo. It’s like having been in a cult and then emerging to realize there’s another reality out there. If we don’t emerge from Burgess’s linguistic brainwashing —and neither the early edition of the novel or the film encourage us to—we remain with the impression that there’s something magnet about Alex. Fascists thrive off of such glamor.

GOP Rep. Mike Turner, chair of the House Intelligence Committee, recently warned that “Russian propaganda has taken hold among some of his House Republican colleagues and is even ‘being uttered on the House floor.’” His comments seconded what GOP Rep. Michael McCaul, Chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, said a couple of days earlier about Russian propaganda taking root among the GOP. Such conditioning is captured in the popular MAGA tee-shirt, “I’d rather be Russian than a Democrat.”

A number of GOP members appear to be channeling Vladimir Putin, including Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, Ohio Sen. J.D. Vance, Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley, and New York Rep. Elise Stefanik. The violence that is always at the back of authoritarian thinking provides them with a special thrill.

The problem is not only on the right. We are seeing some leftwing protesters directly parroting Hamas slogans and calling for the destruction of Israel. They too get a high from the prospect of lashing out. Conditioning can affect ideologues of all stripes.

So what are we to think about a book that enacts the conditioning process? I worry that literature that speaks only to the gut and not to the head is potentially dangerous. In fact, it was this fear that led Burgess to disavow his novel. While doing a good job at depicting the attractions of juvenile delinquent culture, he doesn’t provide the reader with a powerful counter perspective from which to assess it. His last chapter was meant to provide that counter perspective but the publishers were right that it lacks the juice of the earlier chapters.

A better novel would have found a more compelling way to show the soul-draining emptiness of Alex’s destructive energies. Shakespeare is a master at providing such a three-dimensional perspective, and Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky and Faulkner do a pretty good job as well. That’s the difference between great literature and lesser literature.