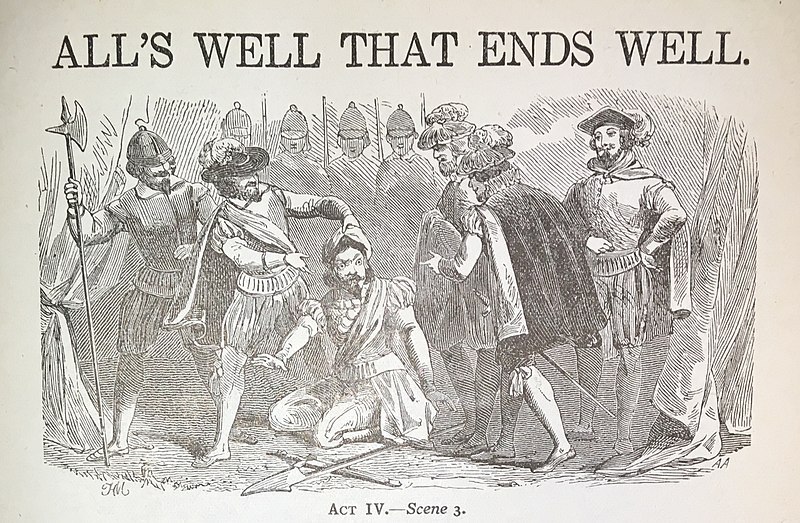

Parolles exposed as a fraud in All’s Well That Ends Well

Wednesday

Doonesbury applied Shakespeare to current affairs in an imaginative way in Sunday’s strip. B.D. overhears his wife Boopsie involved in an on-line bashing (or so he thinks) of a certain ex-president. Here is what he hears:

“I want to hear the outrage.”

“A most notable coward! An infinite and endless liar! An hourly promise-breaker.”

B.D. explodes, shouting, “The trial’s over! He’s off twitter! He’s gone! Why is everyone still obsessing over the former guy.”

Only it so happens that he’s overhearing an acting workshop, with the participants acting out a scene from All’s Well That Ends Well.

Here’s the passage, which describes the loathesome Parolles, a supposed friend of the count who is eventually exposed as…well, one of the Count Bertram’s friends says it best:

Believe it, my lord, in mine own direct knowledge, without any malice, but to speak of him as my kinsman, he’s a most notable coward, an infinite and endless liar, an hourly promise-breaker, the owner of no one good quality worthy your lordship’s entertainment.

Once B.D. realizes he’s hearing Shakespeare, he wonders, “How could he be so spot on?” Which is another way of saying (in the words of Ben Jonson), “He was not of an age but of all time.”

The parallel proves even more apt when one dives into the play. Parolles, whose name is taken from the French word for words (paroles), is essentially a bullshit artist. A kind of Falstaff figure, he all but takes over the play, so much so that 19th century productions were sometimes staged under the name “Parolles.” Like Falstaff (and Trump), he talks a better battle game than he delivers, proving an actual coward on the battle field. As the admirable Helena remarks, “You go so much backward when you fight.”

On the other hand, he talks endlessly about penetrating virgins. Helena, who has her heart set upon Bertram, is nice to him only because he is Bertram’s good friend (“I love for him for his [Bertram’s] sake”). While she (unlike Bertram) sees him for what he is, she nevertheless expresses admiration for how well he carries off his fraudulence:

And yet I know him a notorious liar,

Think him a great way fool, solely a coward;

Yet these fixed evils sit so fit in him,

That they take place, when virtue’s steely bones

Look bleak i’ the cold wind: withal, full oft we see

Cold wisdom waiting on superfluous folly.

If Parolles were virtuous, he would look “bleak i’ the cold wind.” Who wants “cold wisdom” when they can have “superfluous folly”? I think of Texas Republican Senator John Cornyn complaining recently about how boring Joe Biden is:

The president is not doing cable news interviews. Tweets from his account are limited and, when they come, unimaginably conventional. The public comments are largely scripted. Biden has opted for fewer sit down interviews with mainstream outlets and reporters. Invites the question: is he really in charge?

To which Andrew Feinberg observed,

Senator Cornyn appears to be under the impression that presidents are only “in charge” if they spend their time erratically tweeting about what they see on cable news and calling into TV shows.

One way in which the play diverges from our own reality is that, after he is exposed, Parolles falls out of favor and, by the end of the play, is groveling to retain a place at court. Trump, who has been exposed multiple times, still has Republicans making pilgrimages to Mar-a-Lago to pay him homage.

In the play, Bertram is guilty of Parolles’s irresponsible use of words, using them to weasel out of his forced marriage to Helena. Only at the end of the play does he recognize her worth and settle into responsible adulthood. It’s a bit like the ending of Henry IV, Part II where Hal decides to become a responsible king and casts off Falstaff. “I know thee not, old man,” he famously says.

If we see this as an allegory for our own situation, it’s what we want from the Republican Party. They must their infatuation with their bullshit artist—not to mention empty words generally (Fox News, shock radio jocks)—and settle into responsible governance with the opposition party (Helena). Until they do so, our realm will continue to totter.

Then again, if we are lucky, maybe one day we will be able to look back at this polarized time and say, “All’s well that ends well.”

Further thought: While All’s Well That Ends Well isn’t Shakespeare’s best, I have a soft spot for it as I saw Judy Dench perform the count’s mother in a production in Stratford-upon-Avon’s Royal Shakespeare Theatre. As such, she’s in alliance with daughter-in-law Helena against her son Bertram. I remember one scene where she packed a tremendous amount of power into a tiny hand gesture—I felt thrown back in my seat—as she dismisses Bertram when he’s throwing a temper tantrum. At that moment I got why Dench is one of the most admired actresses in British history.