Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Monday

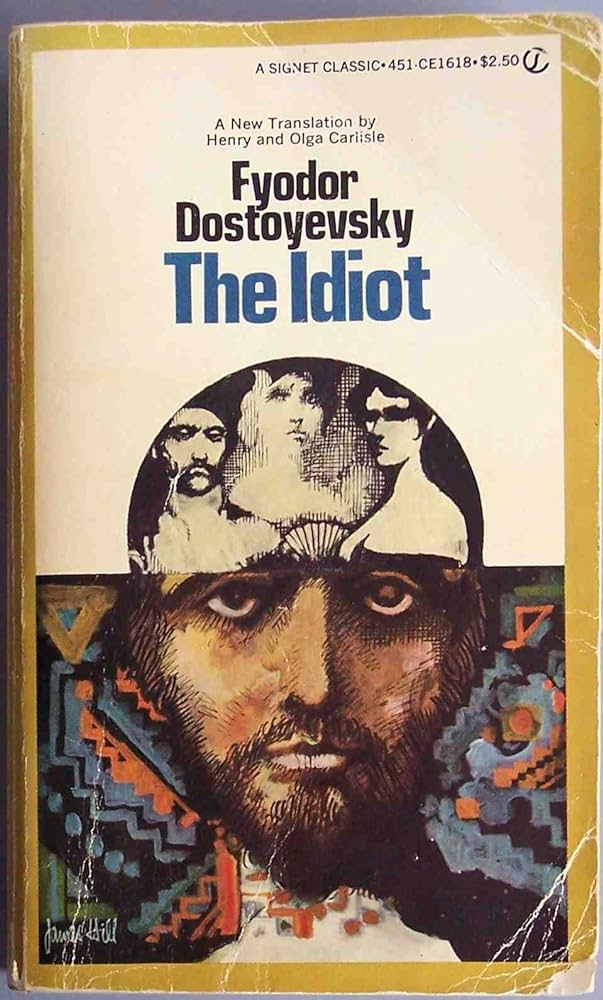

A dear friend who, as an early Covid sufferer, had a near death experience, recently sent me a Scientific American article about NDEs. My friend spent a month on a ventilator and, at a moment when doctors had all but given up on her, she had vision that she can recall vividly to this day. I cite the article here because it draws on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel The Idiot for a description.

Neuropsychologist Christof Koch notes that there’s uniformity amongst NDE reports:

NDEs are not fancy flights of the imagination. They share broad commonalities—becoming pain-free, seeing a bright light at the end of a tunnel and other visual phenomena, detaching from one’s body and floating above it, or even flying off into space (out-of-body experiences). They might include meeting loved ones, living or dead, or spiritual beings such as angels; a Proustian recollection or even review of lifetime memories, both good and bad (“my life flashed in front of my eyes”); or a distorted sense of time and space.

Koch says that NDEs can be both positive and negative:

The former receive all the press and relate to the feeling of an overwhelming presence, something numinous, divine. A jarring disconnect separates the massive trauma to the body and the peacefulness and feeling of oneness with the universe. Yet not all NDEs are blissful—some can be frightening, marked by intense terror, anguish, loneliness and despair.

One can see how narratives of heaven and hell have grown out of NDEs. Indeed, religious people often use them as confirmation. But as a scientist, Koch doesn’t search for metaphysical explanations and notes that there are other experiences—he calls them NDE-lite—that resemble NDEs. One of these involves epileptic fits, also known as complex partial seizures:

These fits partially impair consciousness and often are localized to specific brain regions in one hemisphere. They can be preceded by an aura, which is a specific experience unique to an individual patient that is predictive of an incipient attack. The seizure may be accompanied by changes in the perceived sizes of objects; unusual tastes, smells or bodily feelings; déjà vu; depersonalization; or ecstatic feelings.

Koch says that the last items on the list feature in what are clinically known as Dostoyevsky seizures because the author—who suffered from severe temporal lobe epilepsy—describes them memorably in The Idiot.The novel’s protagonist is the Christ-like Prince Myschkin:

During his epileptic fits, or rather immediately preceding them, he had always experienced a moment or two when his whole heart, and mind, and body seemed to wake up to vigor and light; when he became filled with joy and hope, and all his anxieties seemed to be swept away forever; these moments were but presentiments. As it were, of the one final second (it was never more than a second) in which the fit came upon him. That second, of course, was inexpressible. When his attack was over, and the prince reflected on his symptoms, he used to say to himself: …”What matter thought it be only disease, an abnormal tension of the brain, if when I recall and analyze the moment, it seems to have been one of harmony and beauty in the highest degree—an instant of deepest sensation, overflowing with unbounded joy and rapture, ecstatic devotion, and completest life?…I would give my whole life for this one instant.

Koch says that neuroscience is now able to induce these ecstatic feelings, which Dostoevsky described 150 years ago, by

electrically stimulating part of the cortex called the insula in epileptic patients who have electrodes implanted in their brain. This procedure can help locate the origin of the seizures for possible surgical removal. Patients report bliss, enhanced well-being, and heightened self-awareness or perception of the external world. Exciting the gray matter elsewhere can trigger out-of-body experiences or visual hallucinations. This brute link between abnormal activity patterns—whether induced by the spontaneous disease process or controlled by a surgeon’s electrode—and subjective experience provides support for a biological, not spiritual, origin. The same is likely to be true for NDEs.

Just because science can duplicate the experience does not mean that they don’t have a mystical aspect, however, just as our possession of Richard Dawkins’s “God gene” doesn’t disprove the existence of God. All we know is that the more we delve into the natural world—including the brain—the more amazing it appears, a constant unfolding. Genius authors like Dostoevsky, whose creativity also defies scientific understanding, open up windows into this infinitely complex universe.

Sigmund Freud, who founded psychoanalysis, credited literature–especially the plays of William Shakespeare and the ancient Greek tragedians–as having provided him with his most profound discoveries. First literature paves the way, then the scientific mind scrambles to catch up.

Yet another argument for a liberal arts education.