Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

Our Lenten study group continues to discuss John Gatta’s book Green Gospel, which appears particularly timely given that (following yesterday’s primaries) the GOP has all but chosen a man who promises to “drill, drill, drill” if he becomes “dictator on day one.” Even if Trump loses in November, Gatta reminds us that “we are unlikely in this century to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Centigrade and will be hard pressed, even with serious mitigation measures, to limit it to 2 degrees Centigrade.” Indeed, it appears

already be too late to reverse the overall slide toward atmospheric degradation, too late to restore the wondrous old earth of preindustrial recollection, still largely in view just a few decades ago. The radically accelerated pace of greenhouse gas absorption into the atmosphere during the last thirty years means that this momentous transformation took place during an interval when the world had already been alerted to the peril that excessive emissions posed to life as we know it. Never has the human proclivity toward denial been so disheartening and so dangerous. Without some currently unforeseen breakthrough in technology, apparently the best outcome we might expect now is an appreciative mitigation of those otherwise grave debasements of planetary life that now seem likely.

That being acknowledged, Gatta still counsels hope, and it is this aspect of his argument that I focus on today. In his chapter “Toward a Gospel of Hope, on and for Earth as It Is in Heaven,” he cites John Muir and Emily Dickinson to advocate for what he calls “earth-hearted hope.”

Gatta asks how we are to survive what Mary Evelyn Tucker calls “a tsunami of sadness,” which “engulfs everyone cognizant of the immense losses already suffered or projected to arrive in the wake of climate change.” Hopelessness, he warns, can become “a self-fulfilling stance, even amounting to another form of climate denialism if it ends in passive resignation or despair.”

For a more positive response, Gatta has suggestions. As a Christian, he looks towards religious faith. Theologian Jürgen Moltmann, he notes, articulated a “theology of hope” that “strains after the future” and that, while it seeks inspiration beyond the world as we know it, “does not suppress or skip the unpleasant realities.” One figure buoyed by such faith-based hope, he says, was William Wilberforce, who agitated tirelessly against slavery for much of his life and finally saw it abolished shortly before he died. His faith sustained him throughout “decades of rejection and discouragement.”

But one can also look to nature, and it is here where Muir and Dickinson come in:

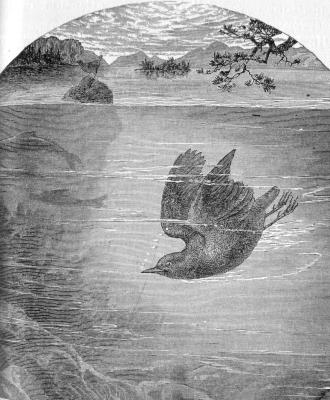

Creatures from the animal realm, too, can teach us something about single-minded persistence. John Muir was much taken, for example, by the irrepressible vigor and endurance of the water ouzel, a diminutive bird of the Sierra who impressed Muir by flying fearlessly into mountain torrents, and by continuing to sing sweetly regardless of storm or seasons. In a similar vein, poet Emily Dickinson chose a bird’s tenacious bearing as her figure of active resolve when she wrote of how “Hope is the thing with feathers / That perches in the soul / And sings the tune without the words /And never stops at all.”

The full poem, as you probably know, goes as follows:

“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all –

And sweetest – in the Gale – is heard –

And sore must be the storm –

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm

I’ve heard it in the chillest land –

And on the strangest Sea –

Yet – never – in Extremity,

It asked a crumb – of me.

By imagining visions of a sustainable future, Gatta says, “we might look together not only to express but also to enlarge our capacity for hope.” Such sustainability includes new forms of renewable energy and efforts “to develop regenerative modes of agriculture, a rewilding of ecosystems and ruined landscapes, and the restorative designation of oceanic ‘no fish zones.’”

Gatta also suggests three personal ways to develop earth-hearted hope. First, one can intensify one’s commitment to pursuing “early-friendly patterns of daily living for oneself,” focusing on “our relation to energy and land use, housing and transportation, toxic consequences of our domestic habits, and our inevitable involvement in food acquisition and consumption.”

Second, one can engage in activism geared toward environmental remediation, at the very least through voting deliberately and offering financial support. Finally, there is “earth-engaged personal meditation, Rule of Life, and sacramental worship.” All of these strengthen our hope muscles.

It so happens that yesterday I was reading a blog post by Rev. Daniel Schultz on how feelings of doom—or DOOM—can function like a virus. As Schultz notes,

DOOM spreads easily: Our brains are tuned to the negative, hyperalert to threat, focused on the evil that may befall us. Expressions of despair and maximal cynicism are quickly picked up and transmitted. The disease vectors of social media make sure of that.

But (and here’s where he agrees with Gatta), he says that hope too is a virus, one which spreads through giving and receiving support. Writing about a 4th century Christian monk who grappled with “acedia” or “a state of restless futility,” Schultz notes that Evagrius Ponticus offered the simple and practical advice “to divide ourselves in two,” with one part to encourage and the other part to be encouraged. “Thus,” Evagrius said, “we are to sow seeds of a firm hope in ourselves.”

“Figuring out how to keep ourselves in the game,” Schultz adds, “helps us to understand what it will take to win other battles.”

As literature professor Gatta knows well, sometimes poetry aids us in that endeavor.