Tuesday

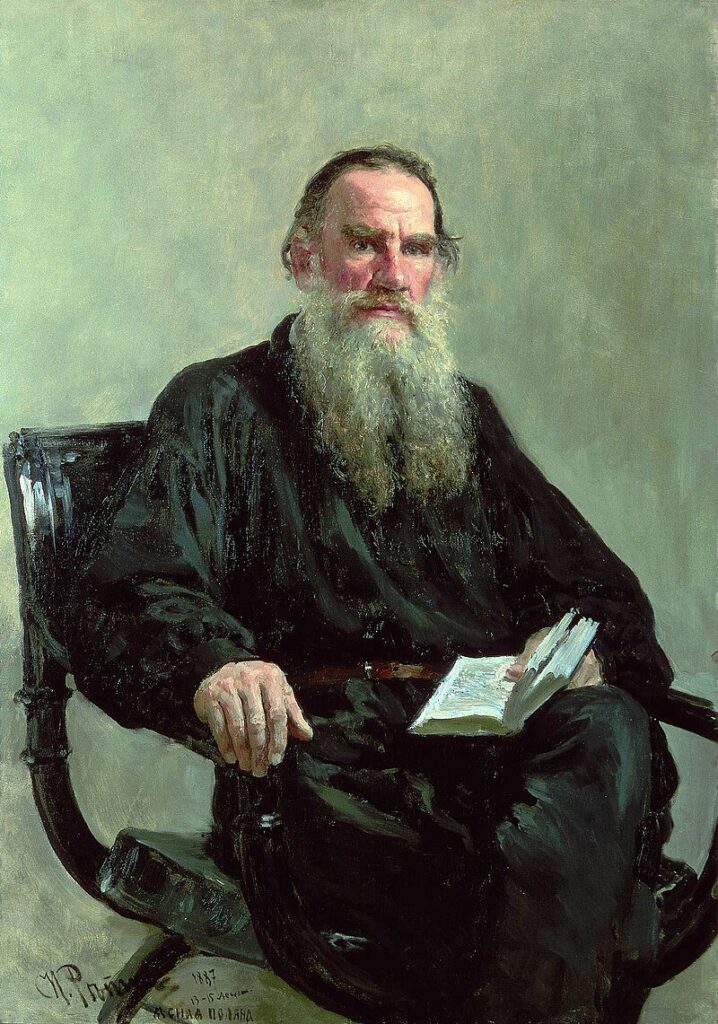

A Nick Romeo article in the latest New Yorker makes a compelling case that economists should be reading literature. Or at least they should be reading Leo Tolstoy’s “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” a short story about a peasant-turned-land owner who spends so much energy trying to amass ever more property that he ends up killing himself.

In the end, the amount he needs is a “six feet from head to his heels”—which is to say, enough to bury him in.

Here’s the situation. The man, who starts off as a poor peasant but finds ways to steadily amass wealth and land, comes upon what seems like an incredible deal: for the tiny price of 1000 rubles, he can have as much land as he can cover in a day of walking. But as the chief of the tribe tells him, “there is one condition: If you don’t return on the same day to the spot whence you started, your money is lost.”

You can imagine what happens next. Every time that the man prepares to return to that original spot, he sees another desirable plot that he can’t imagine not having. All of which leads to this:

Pahom looked at the sun, which had reached the earth: one side of it had already disappeared. With all his remaining strength he rushed on, bending his body forward so that his legs could hardly follow fast enough to keep him from falling. Just as he reached the hillock it suddenly grew dark. He looked up–the sun had already set. He gave a cry: “All my labor has been in vain,” thought he, and was about to stop, but he heard the Bashkirs still shouting, and remembered that though to him, from below, the sun seemed to have set, they on the hillock could still see it. He took a long breath and ran up the hillock. It was still light there. He reached the top and saw the cap. Before it sat the Chief laughing and holding his sides. Again Pahom remembered his dream, and he uttered a cry: his legs gave way beneath him, he fell forward and reached the cap with his hands.

“Ah, what a fine fellow!” exclaimed the Chief. “He has gained much land!”

Pahom’s servant came running up and tried to raise him, but he saw that blood was flowing from his mouth. Pahom was dead!

Why is this essential reading for economists? Romeo explains that our view of economics has become so distorted that we’ve all become Pahoms. While economists like Maynard Keynes once believed that “many major topics of economics are inescapably moral and political” and that “a master-economist” must be “mathematician, historian, statesman, philosopher,” that changed in the 1950s. That’s when Milton Friedman argued that economics could be “an ‘objective’ science, in precisely the same sense as any of the physical sciences.” As a result, ethical and political questions were sidelined and economists began deploying “a technocratic, quasi-scientific vocabulary.”

“From this perspective,” Romeo writes, “the moral evaluations of Keynes, Tolstoy, or anyone else are irrelevant.”

I note in passing that something comparable happened to literary criticism in the 1950s. Instead of looking at how, say, literature can enrich and improve our lives, the formalist critics focused on studying texts the way scientists study natural phenomena. Morality and moral impact appeared irrelevant.

The result of stripping morality out of economics has been severe. The “pose of scientific impartiality,” Romeo writes,

allows mainstream economists to smuggle all sorts of dubious claims—that economic growth requires high inequality, that increasing corporate concentration is inevitable, or that people can only be motivated to work by desperation—into policy and discourse. This becomes an excuse for maintaining the status quo, which is presented as the result of inevitable and immutable “laws.” In the famous phrase of Margaret Thatcher, “There is no alternative.”

The good news is that it doesn’t have to be this way. Romeoo says that we can marry economics and morality

by adopting economic models and policies that give tangible reality to the otherwise empty platitude that a better world is possible. Initiatives such as participatory budgeting, climate budgeting, job guarantees, employee ownership, true prices, genuine living wages, a public utility-style job market for irregular labor, less dogmatic economics education and new investment-capital models that decrease wealth inequality are all powerful elements of a more just and sustainable economy.

Romeo adds that all of these already exist. “There’s no stronger response to charges of utopianism,” he declares, “than showing models that are already working.”

One of the values of a liberal arts education is that students are required to leave disciplinary silos and make connections across disciplines. Having economics majors read Tolstoy is one way to get them to grapple with the moral dimensions of their specialty, just as having literature majors take economics forces them to grapple with how money works. Everyone benefits.