Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Friday

An episode from The English Patient, which I finished listening to on Tuesday, has helped me understand a pivotal point in my father’s life. I think I now know why, at 22, he turned away from his religious upbringing and became an ardent pacifist, a fatalistic determinist, a member of the War Resisters’ League, and a lifelong activist. It involves the concentration camp at Dachau, which he witnessed three days after it was liberated, although this is not the pivot point I have in mind, traumatic though it was.

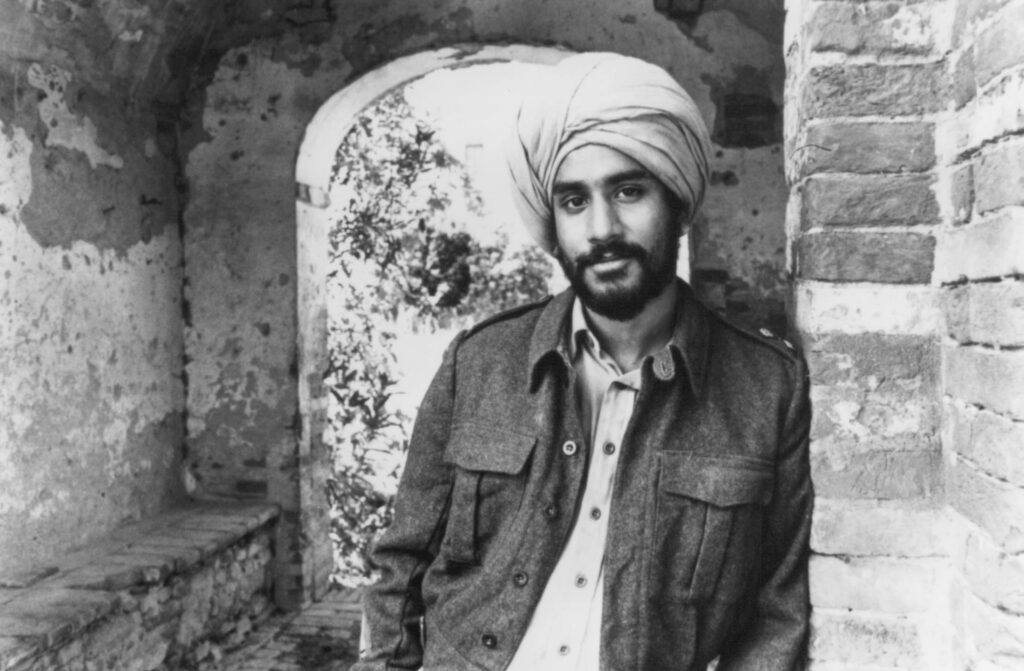

Before getting to his World War II experiences, here’s the episode in Michael Ondaatje’s novel. Four individuals—a Canadian nurse named Hana, a Sikh bomb expert nicknamed Kip, a Canadian-Italian thief, and a severely burned “English patient”—have formed a community within a partially destroyed Italian monastery following Victory in Europe day. A love relationship is developing between Hana and Kip who, despite his brother’s admonitions against ever trusting Europeans, has come from India and joined a British bomb squad. All seems well until Kip hears a piece of news on the radio:

She sees him in the field, his hands clasped over his head, then realizes this is a gesture not of pain but of his need to hold the earphones tight against his brain. He is a hundred yards away from her in the lower field when she hears a scream emerge from his body which had never raised its voice among them. He sinks to his knees, as if unbuckled. Stays like that and then slowly gets up and moves in a diagonal towards his tent…

It so happens that Kip is going for his rifle. Seemingly unhinged, he brings it into the sickroom, apparently prepared to shoot the English patient. When he finally speaks, it is out of disillusion and a deep sense of betrayal:

I grew up with traditions from my country, but later, more often, from your country. Your fragile white island that with customs and manners and books and prefects and reason somehow converted the rest of the world. You stood for precise behavior.

And further on:

You and then the Americans converted us. With your missionary rules. And Indian soldiers wasted their lives as heroes so they could be pukkah [gentlemen]. You had wars like cricket. How did you fool us into this? Here…listen to what you people have done.

The news on the radio is about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, about which Kip says,

When you start bombing the brown races of the world, you’re an Englishman. You had King Leopold of Belgium and now you have fucking Harry Truman of the USA. You all learned it from the English.

Kip’s anger is not only at the British but at himself for ignoring his brother and believing in what he sees as their false claims to a higher civilization:

My brother told me. Never turn your back on Europe. The deal makers. The contract makers. The map drawers. Never trust Europeans, he said. Never shake hands with them. But we, oh, we were easily impressed—by speeches and medals and your ceremonies. What have I been doing these last few years? Cutting away, defusing limbs of evil. For what? For this to happen?

Kip then walks out of their lives, never to be seen by them again.

So here’s my theory of how Hiroshima and Nagasaki traumatized my father. Some background is needed first. One of his jobs when he was stationed in Munich in 1945 was to take Germans on compulsory tours of Dachau. This way they had to confront what their nation had done rather than writing it off as American propaganda. The horror was so immense that they did everything they could to shift responsibility.

In fact, the only time that my wonderfully kind father ever expresses any anger in his letters home is over their attempts to escape blame. As he wrote on Sept. 17, 1945,

…the Germans seem to think they were liberated from [the ardent Nazis], instead of conquered with them. They aren’t afraid of the rest of the world; they just think it silly that the rest of the world should feel that way about them…

After August 6 and 8, the Germans that my father was taking around Dachau suddenly had new leverage. As my father used to tell me, “They said, ‘You say we were bad, but look at what you did.’” In other words, they used a form of “whataboutism” to feel better about themselves.

Only, with my father, it worked. Like Kip, he had thought he was fighting a battle of good against evil—Dachau showed him evil beyond imagining—only to see his own country unleash Armageddon on two civilian populations.

I knew that Hiroshima and Nagasaki hit him hard, but reading about Kip’s reaction gave me a better sense of just how deep his own sense of betrayal went. Having believed fervently in the war, at 22 he lost faith in his own country and never entirely regained it.

Fortunately, he turned that disillusion to good ends. He broke politically with his Republican family and would spend the rest of his life fighting against the white, male, straight, upper class, warmongering establishment. When I got arrested in an anti-war demonstration following the Kent State killings, he chided me for not having forewarned him. He said would have come up to Minneapolis and gotten incarcerated along with me.

But despite his having made the best of the situation, I was always vaguely aware of the scar. English Patient helped me put my finger on it.