Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951 at gmail dot com and I will send it/them to you. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

Last week I finished listening to Absalom, Absalom!, a Faulkner novel I hadn’t read since Erling Larsen’s contemporary novels class at Carleton College (spring of 1973). All I could remember of that earlier encounter is that it felt like a nightmarish hallucination, which itself was intensified by the end-of-semester madness going on at the time. Listening to it this time was difficult in part because of how Faulkner hammers the reader with the n-word on page after page. Still, I came away feeling that Absalom! provides vital insights into the America’s continuing problems with race.

I felt this way even more after reading a recent Washington Post article on White racial anxieties. Columnist Theodore Johnson poses the question, “[H]ow comfortable are White Americans in a democracy where people of color increasingly hold political power?” He believes this to be “the most important question in the nation today.”

Johnson explains that some form of resistance is guaranteed “when the thinning majority suddenly find themselves governed by racial minorities long stereotyped as less intelligent, culturally inferior, prone to criminality and unsuited for leadership.” We can see this resistance in voter suppression, racial gerrymandering, the infusion of dark money into campaigns and, most dramatically, attempts to overturn legitimate elections. “The Democratic Party,” Johnson points out, “has ushered in a new era of racial diversity in the nation’s most powerful public institutions—and folks are mad about it.”

Insecure White Americans have not been shy, especially since Donald Trump, about openly expressing their fears. As Johnson observes,

A swath of the right has put its cards on the table. Its comments about immigrants, majority Black cities and Black and Hispanic Democratic officials — coupled with conspiracy theories and disinformation — make plain the fears it harbors about living in a nation where people of color genuinely participate in power.

I cannot sort through all the racial intricacies of Absalom, Absalom! in a single post but here are a few observations. First, the incessant use of the n-word is not only a way of degrading another race, although that’s certainly part of it. The epithet also grows out of panic that the hard lines of demarcation cited by White supremacists are actually porous. The characters use the n-word to reassure themselves that the boundaries are more fixed than they actually are.

The novel makes clear the instability of race identity. Thomas Sutpen, who has moved to Haiti to learn how to be a slave master, finds himself tricked into marrying a woman of color who is passing as white. He tries to buy off her and her son (Charles Bon) and marries a second time, becoming a secret bigamist. He and his wife have Henry and Judith.

In what may be an elaborate revenge plot concocted by Sutpen’s rejected first wife, Bon ends up at the same college as Henry and proceeds to corrupt him. As though the relationship between these two half-brothers is not already complicated enough, Charles also becomes betrothed to his half-sister Judith. In doing so, furthermore, he is on his way to becoming a bigamist himself, having married an octoroon woman in New Orleans and having had a son by her. Oh, and Henry, Judith, and Charles have one other half-sister, Clytemnestra, whose mother is one of Sutpen’s slaves. In short, what with bigamy, miscegenation, slave rape, and potential incest, the two races are thoroughly intermingled. White insistence that there’s an absolute distinction is belied by the facts on the ground.

One doesn’t have to confine oneself to America’s past to find Whites insisting on this distinction. Cartoonist Scott Adams, author of the Dilbert cartoon series, recently got into trouble by calling Black Americans a “hate group” and suggesting that White people should “get the hell away” from them. While many White Americans, starting with Trump, think this, Adams suffered consequences because he said the quiet part out loud. Again, Faulkner’s novel shows this distinction between “Black Americans” and “White people” to be a false one, especially when one recalls the “one drop of Black blood” criteria that Whites used to distinguish the races. One has but to watch an episode or two of Henry Louis Gates’s Finding Your Roots to realize how mixed up our bloodlines actually are.

Quentin Compson, the historian who is digging into the Sutpen family history, believes that if old Thomas were to acknowledge, even privately to Charles, that he is his father, then Charles would abandon the revenge plot and leave the Sutpens alone. Instead, the father pretends there is no connection:

Then for the second time [Charles] looked at the expressionless and rocklike face, at the pale boring eyes in which there was no flicker, nothing, the face in which he saw his own features, in which he saw recognition, and that was all…

Sutpen cannot bring himself to acknowledge that he has been married to a Black woman, just as certain White Americans today cannot acknowledge that their lives and their histories are inextricably intertwined with Black Americans. Faulkner makes the point dramatically through the intermixed genealogy, but he also makes through the ways that Black and White lives intersect continually in the novel. In Quentin’s “what could have been” alternate history, Sutpen would not have lost his son Henry if he had opened himself to his mixed-race son. Nor would he have begotten another child through the daughter of his handyman in order to replace Henry. Nor would this handyman then have killed Sutpen, along with this daughter and her baby.

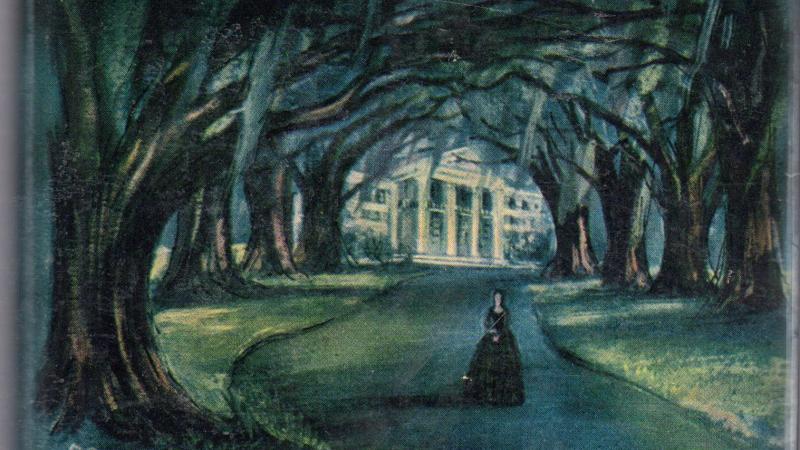

In the novel, the stupendous Sutpen mansion devolves into a gothic haunted house, and it is useful to note that gothic horror relies on repressed truths about ourselves. What we push under, Freud tells us, returns in monstrous guise. When White Americans repress the fact that we are an ethnically diverse and multicultural nation, they project these monstrous images upon people of color. Then unscrupulous politicians and shameless grifters feed upon their projections.

Abraham Lincoln, quoting Jesus, famously said that a house divided against itself cannot stand, and the Sutpen mansion, symbol of a nation that refuses to face up to its diversity, goes down in a fiery blaze at novel’s end. If today we see figures like Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene replaying a dark history–she has called for secession and Civil War–it’s because they still cannot accept what we actually are. As Faulkner famously observed, “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.”

And so we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into what used to be.

Fortunately, not all Whites feel this way. At the end of his Washington Post article, Johnson writes about pushing back against our racially toxic eternal return. “The American experiment only succeeds,” he writes,

when our large diverse nation figures out how to strengthen an egalitarian and participatory democracy. It only fulfills its promise when the republic resembles the people without losing credibility or legitimacy. We are only exceptional if the color of our democracy is not seen as an impediment to the content of the nation’s character.

Faulkner, who knew the South well, shows the depth of the problem. Sadly, the problem extends beyond the south, and it appears that we still have a long way to go.