Spiritual Sunday

I write today about a very exciting book that I’ve just encountered, along with its author, an English professor at Sewanee. John Gatta’s Making Nature Sacred: Literature, Religion, and Environment in America, from the Puritans to the Present addresses some questions I’ve long had about nature’s spiritual dimensions.

Gatta writes that, in America,

no path for pursuing self-transcendence has seemed more enduringly accessible than the one leading nature devotees into the continent’s own forests, fields, river valleys, and mountains.

Gatta points to characters like Natty Bumppo and Huck Finn and authors like Emily Dickinson, Henry Thoreau, Black Elk, Rachel Carson, and Annie Dillard as amongst those having encounters with “the ineffable spirits of nature.” For an example, think of Dickinson’s poem “Some keep the Sabbath going to church”:

Some keep the Sabbath going to Church –

I keep it, staying at Home –

With a Bobolink for a Chorister –

And an Orchard, for a Dome –

Some keep the Sabbath in Surplice –

I, just wear my Wings –

And instead of tolling the Bell, for Church,

Our little Sexton – sings.

God preaches, a noted Clergyman –

And the sermon is never long,

So instead of getting to Heaven, at last –

I’m going, all along.

The connection between nature and Christianity particularly draws Gatta’s attention, and he quotes intellectual historian Perry Miller that

“God speaks to us” with peculiar force “in the sublimity of Nature” and that “America, beyond all nations, is in perpetual touch with nature.”

Yet for all that, most Americans haven’t turned to a pure nature religion, say, an “animistic faith that gods or spirits dwell directly ‘in’ the tree.” Instead, they have supplemented their inherited religions with nature spirituality. Or to put it another way, America’s religions have often evolved to include a strong nature component:

Among the major traditions of world religion, Christianity, not surprisingly, has most deeply affected the ecological outlook of English-speaking North Americans. More particularly, subcultures shaped religiously by Protestant Christianity have dominated imaginative expression in this sphere until the last half century or so, when more eclectically Christian and Catholic versions of ecospirituality have also gained prominence in writers such as Annie Dillard, Barry Lopez, Wendell Berry, and Kathleen Norris.

Gatta mentions also Buddhism’s influence on American nature writing, including such authors as Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder, and Peter Matthiessen. Native American religions, he points out, have a strong emphasis on “spirituality mediated through the nonhuman world,” and the importance of a spiritualized nature is also to be found in African American authors like Zora Neale Hurston and Toni Morrison.

Gatta’s book excites me because it gives a framework for something I have long told my students, that immersing yourself in nature and nature writing deepens you spiritually. I talk about this as I teach such works as Euripides’s The Bacchae and the medieval romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Wordsworth voices such an idea in his sonnet “The world is too much with us,” where the poet notes how capitalism is draining nature of its spiritual dimensions. We can no longer sees gods when we look out at the ocean, he laments.

Nature writers may not speak openly of religion, but if one examines them closely, one can often find that they are using a religious framework to talk of nature’s spiritual influence. To cite an example, it has become a tradition of this blog to share a Mary Oliver poem every Easter. When I first began doing so, I didn’t fully appreciate the degree to which images of Christian suffering and grace suffuse Oliver’s work. Thanks to Gatta, I better understand what Oliver is up to and how she is not alone.

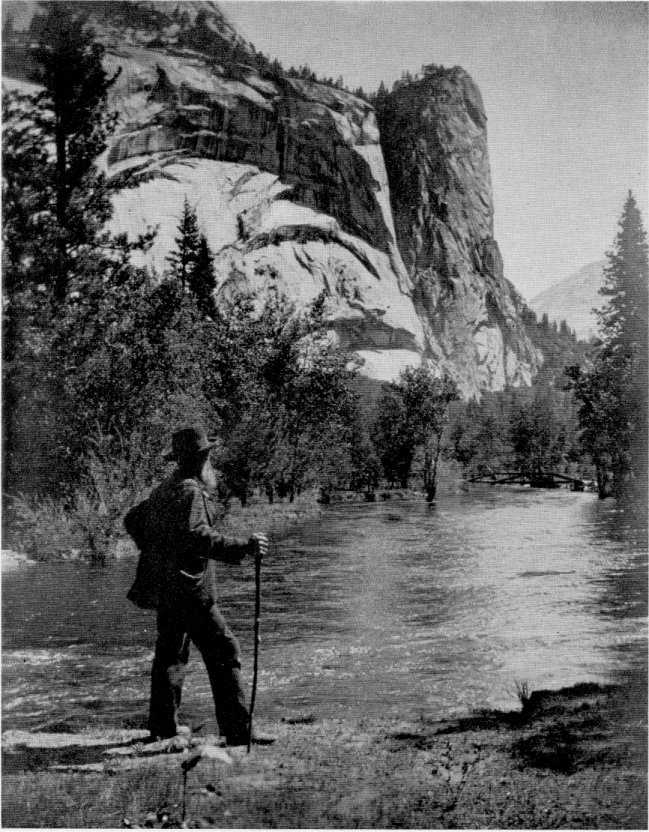

For instance, here he is describing his chapter on John Muir and Rachel Carson:

My reading of Muir, for example, aims to capture the sheer intensity of religious feeling—a piety at once unorthodox and mystical, yet biblically Protestant—that suffused this writer’s naturalism. In this chapter, too, I discuss Rachel Carson’s lifelong aspiration to blend scientific curiosity with a religious indeterminate yet robust spirituality. Resisting strictly materialistic appraisals of nature, Carson was awed by the beauty of what she examined, the beauty of things seen as well as unseen in a nonhuman order whose marvels exceeded human boundaries. Carson’s poetic praise of the world’s inexhaustible wonder and mystery is most evident in her oceanic writings, which expose the contemplative spirituality that informed her larger vision of ecology. This accomplished empirical scientist found herself enchanted, above all, by the concealed beauty of tidal pools set in ocean caves. Carson’s profound sense of “reverence for life” also generated moral passion, a prophetic imperative for change best displayed in the rhetoric of Silent Spring.

Gatta concludes his book with a powerful observation. Drawing on the work of Bill McKibben, he says that we need to preserve the environment to maintain our ability to “imagine anything numinous [divine] in nature”:

Once we construct the physical world so thoroughly that we can no longer see, to rephrase Wordsworth, anything in nature that is not ours, religion itself is endangered along with countless biotic species. McKibben contends that…we need continuing access to real-life “nature” for the sake of our own physical and spiritual survival—and it so happens, for religion’s sake as well.

Or as a character in Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior puts it in a debate over whether God would want an Appalachian farm family to clearcut a mountain:

The land was bestowed on us for a purpose. And I don’t think it was to end up looking like a pile of trash.

The passage points to another important point that Gatta makes: we need religion to save the environment as much as we need the environment to save religion. After all, some of the most powerful environmental activists have been writers writing from the soul:

The imaginative hopes of these visionaries spring from their passionate spirituality, a re-creative impulse that is religious to the core, whatever its relation to tradition orthodoxies. Figures as theologically disparate as Henry Thoreau, John Muir, Wendell Berry, Mary Oliver, and Annie Dillard share not only a passionate interest in wild creatures and places but a conviction that God, too, must be less tame and respectable than has been piously rumored. This other-than-safely-human Maker of all things, visible and invisible, may even be, as Berry claims, the wildest being in existence.”

The astute religion thinker C. S. Lewis tells us that “Aslan is not a tame lion.” When we attempt to whittle either God or nature down to our size, we cut ourselves off from the immensity of creation.