Tuesday

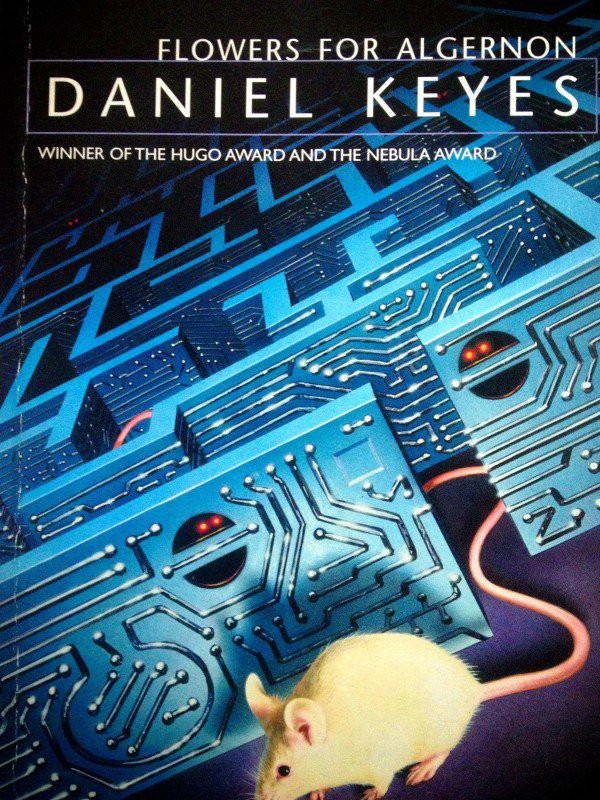

I have an interesting tennis situation that is reminding me of Daniel Keyes’s science fiction novel Flowers for Algernon. To understand why, a plot reminder is useful.

Charles Gordon, who has an IQ of 85, works in a plastic box company until he is selected for special surgery that will make him smarter. When his IQ rises to 185, he realizes, by studying the progress of a mouse that has undergone the same surgery, that the change is only temporary and he will revert back to his initial state. The novel is a tour de force in point of view so that we see Gordon’s prose change with his intelligence, progressing and then regressing in a bell curve.

Tennis has been my sports passion since I was 11, when I received lessons from Sewanee coach Gordon Warden. Over the subsequent years, however, I took few lessons because I was comfortable with my tennis community. If I got too good, I figured, I would outstrip my partners. (Also, for many years I could not afford lessons.) For those who know tennis, I was at a 3.5 level, although I was competitive with 4.0 players.

My decision changed when I retired and saw how much better my game could become. I have therefore been taking lessons every other week with Sewanee’s current coach, John Shackelford, who upon first seeing my game informed me that I had a Ken Rosewall forehand. It took me two years to unlearn this 1960s style and develop a topspin more in accord with modern tennis practice and new racquet technology. Every lesson I am excited to learn new things, from swinging volleys to violently sliced second serves to attacking strategies at the net. I generally play once or twice a day (following Covid protocols, of course) and can report significant improvement.

In Keyes’s novel, however, not everything goes well. As Gordon becomes more intelligent, he outstrips his special ed teacher, with whom he has fallen in love. He experiences such scenes as the following:

I am very disturbed. I saw Miss Kinnian last night for the first time in over a week. I tried to avoid all discussions of intellectual concepts and to keep the conversation on a simple, everyday level, but she just stared at me blankly and asked me what I meant about the mathematical variance equivalent in Dorbermann’s Fifth Concerto.

When I tried to explain she stopped me and laughed. I guess I got angry, but I suspect I’m approaching her on the wrong level. No matter what I try to discuss with her, I am unable to communicate. I must review Vrostadt’s equations on Levels of Semantic Progression. I find that I don’t communicate with people much anymore. Thank God for books and music and things I can think about. I am alone in my apartment at Mrs. Flynn’s boardinghouse most of the time and seldom speak to anyone.

Nothing so extreme is happening with me, of course. For one reason, I’m not improving that much. I can’t hold a candle to members of Sewanee’s championship tennis teams, either the men or the women, and I have plenty of partners who are at my new level. Sewanee, because it has indoor as well as outdoor courts (although Covid has currently closed the athletic center) is a tennis Mecca.

And yet, there are groups of friends who no longer ask me to play doubles with them—and with good reason, given how I skew the results. I no longer play in a Monday Night mixed doubles league set up by a long-time friend.

Will I decline like Charles Gordon? Aging will take its own toll (I am 69), and as I regress I can imagine some of my new partners—those currently in their forties—looking around for other competition. In Flowers for Algernon, Gordon starts panicking once he realizes that decline is on the way. My goal is to age gracefully.

Indeed, one aim of my lessons is to learn how to put less wear and tear on my body. I have always been a quick and energetic player—I run constantly, reluctant to give up on any ball—but with better racquet work, decision making, and placement, I can play a more sedate game. I am gradually learning the wisdom of a defensive lob. I am also learning (though it pains me to do so) that’s it’s okay to concede certain points, say a wicked drop shot when I am on the back line.

I’ve always seen tennis as a metaphor for life. Keyes’s novel, while it focuses on an individual with special needs, touches on how even the healthiest of us are only temporarily abled. As his IQ plummets back to its original 68, Gordon chooses not to return to his old workplace because he doesn’t want to experience the pity of his fellow workers. One could say that he rages against the dying of the light.

I’m hoping that I will accept the inevitable decline, enjoying tennis at whatever level is available to me. I’ll report back from time to time on how I’m doing.