Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday

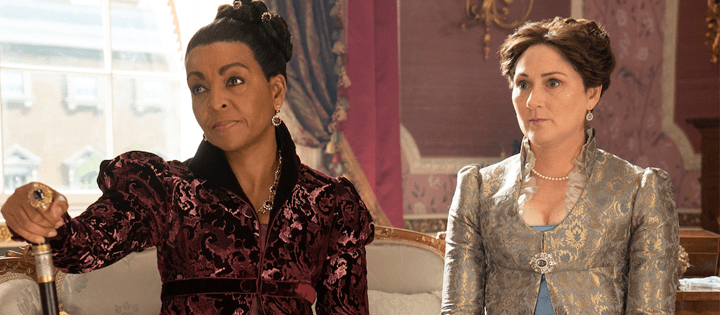

Julia and I are currently caught up in Queen Charlotte, the Netflix series about King George III’s wife. The series includes Violet Bridgerton from Netflix’s Bridgeton series, whom we see developing a moving friendship with Lady Danbury. These two elderly widows buck convention by talking about their sexual yearnings—this in a society where women aren’t supposed to have such yearnings and certainly not to talk about them. As I watched, I thought that they would have benefitted from the poetry of a near contemporary, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. (The story is partially set in 1760 while Montagu died in 1762.)

A skilled satirist, Montagu was an early feminist. She skewered the carpe diem message of “gather ye rosebuds while yet may” in a brilliant lyric “The Lover.” If I turn you down, she tells her wooer, it’s not because I’m cold (“a virgin in lead”) or prudish (“Nor is Sunday’s sermon so strong in my head”). Repeating some of the carpe diem poets’ familiar arguments, she says, “I know but too well how time flies along, /That we live but few years, and yet fewer are young.” But, she adds, “I hate to be cheated, and never will buy/ Long years of repentance for moments of joy.”

The two elderly widows in Queen Charlotte need not worry about rakish suitors, however, so I have two other poems that would do them good. One of them, written in Montagu’s later years, captures her sadness over frustrated longing, asking, “What cure for those who wish in vain?” While Montagu says she could give up desire for fame, wealth, and beauty, this longing is a grief she cannot “bear or cure.” “Clarinda” is a self-reference:

Exil’d, grown old, in Poverty and Pain;

Philosophy could calm the Poet’s breast:

But oh! what cure for those who wish in Vain!

What Lesson is it must restore my Rest?Let others court the mighty Idol Fame;

Let all the World forget Clarinda’s Name,

I could lose all that Avarice requires

Of all that Beauty that the World admires,

This only grief I cannot bear or cure,

The firmness of my Soul gives way,

Some pitying Power behold what I endure

The other poem is angrier, written as it was in defense of a woman who was sued successfully by her husband because of an affair, even though he himself was a notorious womanizer. (The courts granted him control of her money.) “Epistle from Mrs. Yonge to Her Husband” is written from the wife’s point of view and was too controversial to be published. The part that applies to Ladies Bridgerton and Danbury is Mrs. Yonge’s declaration that she too has emotional needs:

Are we not formed with passions like your own?

Nature with equal fire our souls endued,

Our minds as haughty, and as warm our blood;

O’er the wide world your pleasures you pursue,

The change is justified by something new;

But we must sigh in silence—and be true.

And then there’s the anger at her hypocritical husband not allowing her to fulfill her own desires quietly and discreetly:

But you pursue me to this last retreat.

Dragged into light, my tender crime is shown

And every circumstance of fondness known.

Beneath the shelter of the law you stand,

And urge my ruin with a cruel hand…

Lady Bridgerton and Lady Danbury are never unfaithful to their husbands so that part of the poem doesn’t fit their situation. But both know well that society would mock them if their sexual desiring were “dragged into light.”

Poems like these would bolster the two women considerably.