Spiritual Sunday

I have found myself exploring Gnosticism thanks to a marvelous poetry collection by my best friend from graduate school, Norman Finkelstein (the poet, not the political scientist). Norman has been included in a group of poets labeled “the New Gnostics,” which helps me make sense of From the Files of the Immanent Foundation. I’ll review the collection in a future post, but today I reflect upon Gnosticism’s influence on poetry generally.

Gnosticism believes that the material world has been created by a lesser god (the demiurge), who has trapped the divine spark within the human body. This spark can be released through gnosis or spiritual knowledge.

Gnosticism arose out of 2nd century Judaism and Christianity. Jewish Kabbalists scrutinized the Torah for secret knowledge while Christian Gnostics saw Jesus as an angel sent to teach humans how to release the spark. Although the Christian church would eventually declare Gnosticism a heresy, it has never entirely disappeared, and poets in particular have been drawn to it.

Poet Patrick Pritchett, in a delightful list, draws up a long list of authors he considers to be gnostic. I’ve picked out those poets best known to English-speaking audiences and included in brackets some of the works Pritchett may have in mind:

–I don’t care what Ted Hughes says. Shakespeare was not a gnostic. Except in Lear and The Tempest.

–Henry Vaughan is a gnostic of eternity’s endless ring of light. [“The World”]

–Kit Smart is a gnostic of cats, for they roll in their prank. [Jubilate Agno]

–Blake is a gnostic of Blake and all his angels.

–Shelley was a gnostic who sailed to the moons of Italy. [“The Cloud”]

–Keats got drunk on a ripe gnostic vintage before he was engulfed in a cloud of blood. [“Ode to a Nightingale”]

–Could Hopkins be a gnostic? Like a kingfisher catching fire? [“As Kingfishers Catch Fire”]

–Herman Melville is a gnostic. He was burned in the darkness of the sea and the blind hills of Pittsfield and the whiteness of the unknowable. [Moby Dick]

–Emerson is a gnostic when he says that the way of life is abandonment. [“Circles”]

–Poe is the gnostic who saw nature for what it is: a gaping hole ready to devour us. [“Descent in the Maelstrom”]

–Whitman is a gnostic of the open road and the electric body and the emancipation of song. [Song of the Open Road, I Sing the Body Electric, Song of Myself]

–Dickinson is a gnostic of the white bone of the word. [“There is a poem—so utter—”]

–Kafka is a gnostic of infinite delay, otherwise known as grace. [The Castle]

–Lovecraft is the true gnostic of the deep weirdness of alien gods and the bottomless abyss of time. [“The Dunwich Horror”]

–Pound began as a gnostic, moving the souls of the dead through the facets of the phantastikon. But he burned his days to the ground. Still, “All things that are, are light.” [Pisan Cantos]

–HD stayed gnostic to the end, singing of a light inside the seashell that was Helen’s ear. [“The Walls Do Not Fall”]

–Hart Crane, tormented by gnosis he sang Atlantis from ruin to America, then he laid him down in his watery grave. [“Atlantis”]

–Lorca is a gnostic of duende, where the silver coins sob under moonlight on the road to Cordoba. [“The Moon Wakes”]

–Yeats, a Celtic gnostic. Chanting of Fergus and Byzantium and translunar paradise. [“Who Goes with Fergus,” “Sailing to Byzantium,” A Vision]

–Jung is a gnostic of the alchemical rose and the dead speaking from the drowned book of dreams. [The Practice of Psychotherapy]

–Simone Weil was a gnostic of affliction. [The Love of God and Affliction]

–James Agee was a gnostic of the poor and the soft summer nights of Alabama and his own deluded alcoholic beatitude. [Now Let Us Praise Famous Men]

–Camus? Possibly an existentialist gnostic of Algerian sunlight and shadow and the hunger for justice and of a cigarette dangling from his lips. [The Stranger].

–Stevens is a gnostic of the dandelion and the summer lawn and the ghosts of angels thronging drunk in the late light of New Haven. [“A Rabbit as King of the Ghosts”]

–Kerouac is a gnostic of the dark car crossing America all night long for brotherly love. [On the Road]

–Ginsberg is a gnostic of wanting to be fully alive amid Blakean visions and whirling sutras and the simple compassion of one person for another.

–Tolkien is a gnostic of Sauron. Think about it. [Lord of the Rings]

–Pynchon and DeLillo are gnostics of the radioactive sublime. [Gravity’s Rainbow, Underworld]

–Beckett wrote the book of the ruins of gnosis. To fail at failure is all we can do now. Spirit’s nothing. Nothing’s spirit. A voice that comes to one in the dark. Go figure [Worstword Ho!].

To be sure, as Pritchett admits elsewhere, “because Gnosticism has become such an elastic term, used to describe such a wide swath of writers, often as different from one another as, say, Poe and Emerson, that it threatens to lose is usefulness as meaningful category.” Indeed, Pritchett’s list suggests that practically any author who uses poetic language to capture the spiritual dimensions of life outside traditional religion (and even within traditional religion, e.g. the Anglican Vaughan and the Catholic Hopkins) could be labeled a gnostic.

That being said, “gnostic” describes fairly well what, say, Shelley is up to in his poem mourning Keats (Adonais). The “one Spirit” is a creative force that blows through the universe, interacting with and seeking to infuse “th’unwilling dross” of “the dull dense world.” The dross reflects the Spirit to the extent that its material existence allows it to (“as each mass may bear”):

He is a portion of the loveliness Which once he made more lovely: he doth bear His part, while the one Spirit’s plastic stress Sweeps through the dull dense world, compelling there, All new successions to the forms they wear; Torturing th’unwlling dross that checks its flight To its own likeness, as each mass may bear; And bursting in its beauty and its might From trees and beasts nd men into the Heaven’s light.

According to Shelley, Keats’s lovely poetry captured this Spirit as it blew through the world. For gnostic poets, poetry functions as a kind of prayer that seeks to (in Pritchett’s words) “redeem[ ] the ruins of history and the disjointedness of everyday life.” For the New Gnostics, poet Henry Gould says, poetry is “a spiritual discipline, dedicated to a sacred mystery.”

Poet Peter O’Leary, setting forth “the Seven Tenets of the New Gnosticism,” says “you are initiated into the New Gnosticism whenever you contribute to its incantations.” I take this to include reading as well as writing gnostic poetry.

One problem with traditional Gnosticism is how it rejected the world and the body altogether because, as matter, they trap the spirit. This is one reason why Christianity, once it became Rome’s official religion, condemned Gnosticism as a heresy. The Church wanted people engaging with the fallen world, not turning from it in revulsion. Institutionalists were understandably adverse to mystics running the show

In a frank assessment of the New Gnostics, poet Henry Gould says that they are illogical and “somewhat incoherent” on the question of matter and want to have it both ways, believing that “bodily existence is a matter both of shared suffering and of shared enlightenment/joy.” If matter imprisons spirit, then how can you celebrate the prison guard?

Another problem, Hughes points out, is that Gnosticism believed in “a secret knowledge to which only bands of the elect, of inspired and persecuted geniuses, have access.” Hughes notes that this belief continued into Yeats, Pound, and modernism in general, and the New Gnostics ascribe to it. When poetry requires esoteric knowledge of its audience, many casual readers stop reading poetry altogether.

In the New Gnostics’ defense, Gould says they are “not afraid to speak of and express love,” unlike the intensely ironic Language Poets who preceded them. To demonstrate his point while showing a New Gnostic sensibility at work, I share a tender love poem from Immanent Foundation. Norman addresses it to his wife Alice.

Like a gnostic seeking divinity, Norman finds Alice in the “broken heart of the world” and believes that “in you mysteries are solved, hidden arguments resolved.” “No passions cool in her presence,” he adds.

She, on the other hand, realizes that, for him, “I was always and only the beloved.” Their subsequent joint observation that they were “always and already absent” may refer to a mysterious space in the relationship that puts it outside of time and language and that is to be filled by heavenly agents.

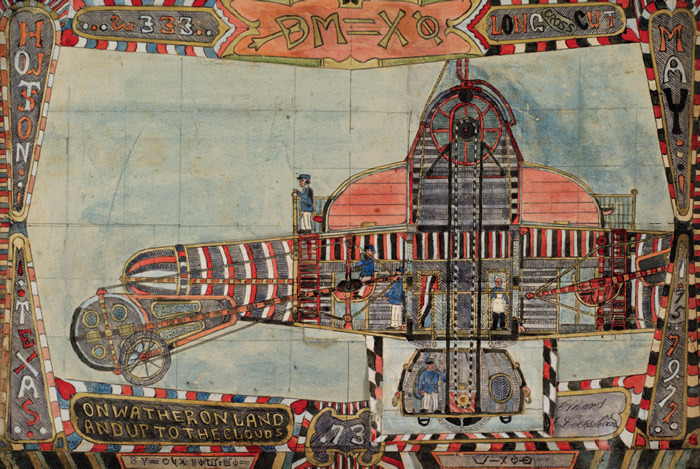

The phrase “On Wather on Land and Up to the Clouds” refers to an inscription on one of Charles A. A. Dellshau’s myserious drawings (see the above illustration). A 19th century outsider artist who figures heavily in Norman’s book, Dellshau suffered unimaginable personal losses but, late in life, poured his losses into his art, drawing thousands of possible airships. The dream of flight is a dream of transcendence.

“Fly into the world as you fly from it,” Norman instructs us. Flight, like love, takes us up to the clouds, and when we leave the earth, “love will fly to you.”

Epilogue

3.

for Alice

Heart of the world, secret, broken

heart of the world; you are everywhere

and nowhere; you are what remains

and what is to be found. In you

mysteries are solved, hidden arguments

resolved. In this account (he wrote),

no passions cool in her presence;

in his account (she observed),

I was always and only the beloved.

And yet we (they) were always

and already absent, and as an absence,

agents sought us (them), On Wather

On Land and Up to the Clouds. Pour

your losses into your art. Mysterious

and hidden, what you make is made

of what you are. Rise up now

and in your wish to fly, flight

will take you where you want to go.

Fly into the world as you fly from it;

fly and love will fly to you.

Added note: Speaking of gnostic poets, when I dined with Alan Ginsburg during his visit to St. Mary’s and revealed that I was an 18th century British literature scholar, he rhapsodized about Christopher (Kit) Smart, especially Jubilate Agno, where he sings praises to his cat Jeoffry (“For he is the servant of the Living God duly and daily serving him.”). In his reading later that evening, he had all of us singing the Blake line “And all the hills echoed” from “Nurse’s Song” for a full 20 minutes as he accompanied us on a finger pump organ. So yes, all three poets use poetry to approach the numinous.

Further thought: Taking up Pritchett’s challenge to think about Sauron in gnostic terms, I assume Tolkien’s arch-villain represents the matter that threatens to engulf the world, forever trapping the divine. Frodo then would be a gnostic hero, seeking to liberate the divine spark from the heavy drag of the ring. To get at what he’s up against from a gnostic point of view, here’s Peter O’Leary quoting Jacques Lacarriere’s description, in The Gnostics, of suffocating matter:

The world in which we live is not only opaque, heavy, and given over to death, but is above all a world born of a monumental machination; a world that was not foreseen, not desired, flawed in all its parts; a world in which everything, every being, is the result of a cosmic misunderstanding. In this whirlpool of errors, this universal shipwreck which is the history of matter and of man, we on earth are rather like survivors condemned to eternal solitude, planetary detainees who are the victims of injustice on a truly cosmic scale. Stars, ether, aeons, planets, earth, life, flesh, inanimate matter, psyche—all are implicated, dragged into this universal disgrace.