I’ve just written a series of serious posts about literature and virtue, but since it’s Friday, let me go out of the week on a light note. Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones is not admired the way it once was, but one would be hard pressed to find any novel that is funnier. I share here a characteristic instance of the author’s wit.

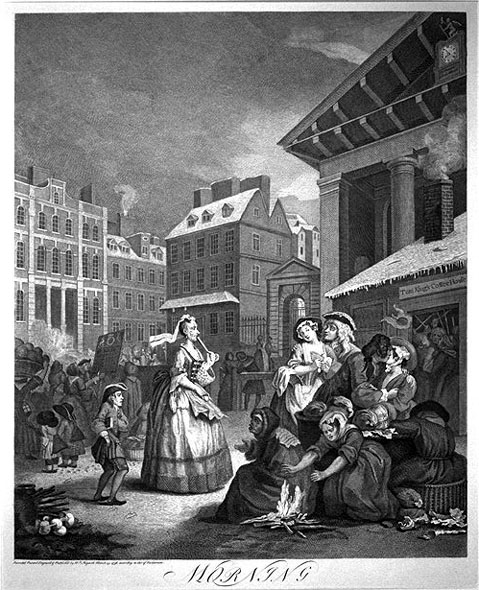

Early in the book, we have a situation that is boilerplate comedy. Bridget Allworthy, sister of the squire who has taken in the foundling Tom Jones, is an aging spinster with money. Modeled on the woman in the Hogarth print above, she wants a husband and there are crass fortune hunters who are only too willing oblige. One of these is a Mr. Blifil, only he has a minor problem:

The doctor found himself so agreeable to Miss Bridget, that he now began to lament an unfortunate accident which had happened to him about ten years before; namely, his marriage with another woman, who was not only still alive, but what was worse, known to be so by Mr Allworthy.

The passage has two punch lines: one when we discover what the “accident” is, the other the unsettling implication of the concluding phrase. What might the doctor have done if Allworthy didn’t know?

Blifil, however, has a brother, a thuggish captain. Fielding is an expert in couching a slam within an apparent compliment, starting out high and then abruptly going low. He describes Captain Blifil as “one of those wise men who regard beauty in the other sex as a very worthless and superficial qualification; or, to speak more truly, who rather choose to possess every convenience of life with an ugly woman, than a handsome one without any of those conveneniences.”

Fielding goes on to say, “To deal plainly with the reader, the captain, ever since his arrival, at least from the moment his brother had proposed the match to him, long before he had discovered any flattering symptoms in Miss Bridget, had been greatly enamoured; that is to say, of Mr. Allworthy’s house and gardens, and of his lands, tenements, and hereditaments; of all which the captain was so passionately fond, that he would most probably have contracted marriage with them, had he been obliged to have taken the witch of Endor into the bargain.”

Such circuitous sentences are one of the hallmarks of Fielding’s comic style. He is like a boxer who dances around his opponent, feinting and bobbing until you’re practically hypnotized—and then delivering a lightning like jab.

Nowhere does he do it better than in the following passage. The Blifil-Bridget marriage is, predictably, a disaster and they quarrel constantly. The captain, however, has one consolation: he can dream of all the changes he will make to Squire Allworthy’s estate once the worthy man dies:

Nothing was wanting to enable him to enter upon the immediate execution of this plan, but the death of Mr. Allworthy; in calculating which he had employed much of his own algebra, besides purchasing every book extant that treats of the value of lives, reversions, &c. From all which, he satisfied himself, that as he had every day a chance of this happening, so had he more than an even chance of its happening within a few years.

But while the captain was one day busied in deep contemplation of this kind, one of the most unlucky, as well as unseasonable, accidents, happened to him. The utmost malice of Fortune could, indeed, have contrived nothing so cruel, so mal-a-propos, so absolutely destructive to all his schemes. In short, not to keep the reader in long suspense, just at the very instant when his heart was exulting in meditations on the happiness which would accrue to him by Mr. Allowrthy’s death, he himself—died of apoplexy.

Do you feel the jab? I love the way that Fielding, promising “not to keep the reader in long suspense” after having already done so, then goes on another 26 words before relieving the suspense. If one is patient with Fielding’s style, it never fails to deliver.

Fielding has further set up the joke with the chapter title, which reads, “A Receipt to regain the lost Affections of a Wife, which hath never been known to fail in the most desperate cases.” And in fact, Captain Blifil’s death does the trick. Bridget dotes on him once again and writes an over-the-top epitaph for his gravestone.

Before leaving the Blifils, let me end with their son, who is the logical product of this perfect union. He and Tom grow up together and the book’s heroine sees both boys clearly:

Sophia when very young, discerned that Tom, though an idle, thoughtless, rattling rascal, was nobody’s enemy but his own; and that Master Blifil, though a prudent, discreet, sober young gentleman, was at the same time strongly attached to the interest only of one single person; and who that single person was, the reader will be able to divine without any assistance of ours.

Analyzing comedy risks compromising it since comedy’s very target is often logic and reason. Suffice it to say, then, that good-hearted comedy such as Fielding’s helps us walk a little lighter on the ground. When the world is too much with us and care hangs over our heads, we owe a lot to an author who (to quote the immortal words of Mr. Bennett in Pride and Prejudice) understands that we live to “make sport for our neighbors, and laugh at them in our turn.”