Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Tuesday

Somehow it happens every four years: I declare that I’m going to resist getting sucked into the Olympics and then I get sucked into the Olympics. Yesterday it seemed a matter of utmost importance whether the sublime Swedish poll vaulter Armand Duplantis would break his own world record. (He’d already won the gold so was only competing against himself at this point.) And whether Noah Lyles would stay on track to add the 200-meter gold to his 100-meter gold. And whether a Kenyan or an Ethiopian would win the 5000-meter race. And so on. Every day has moments like this.

As I watched Lyles win the “fastest man in the world” race on Sunday, I thought of the race in The Odyssey, which may have been composed around the time that the first Olympics was being held (8th or 7th century BCE for The Odyssey, 776 BCE for the first Olympics). The race where the Phaiakians compete against each other is far less exciting than the Lyles race. Then again, at a quarter mile this race would be 400 meters, not Lyles’s 100 meters:

The runners, first, must have their quarter mile.

All lined up tense; then Go! and down the track

they raised the dust in a flying bunch, strung out

longer and longer behind Prince Klytoneus.

By just so far as a mule team, breaking ground,

will distance oxen, he left all behind

and came up to the crowd, an easy winner.

There were no oxen in this race, which everyone ran under ten seconds (!!). Lyles beat out his Jamaican opponent by .005 seconds, leaning just enough to take the victory.

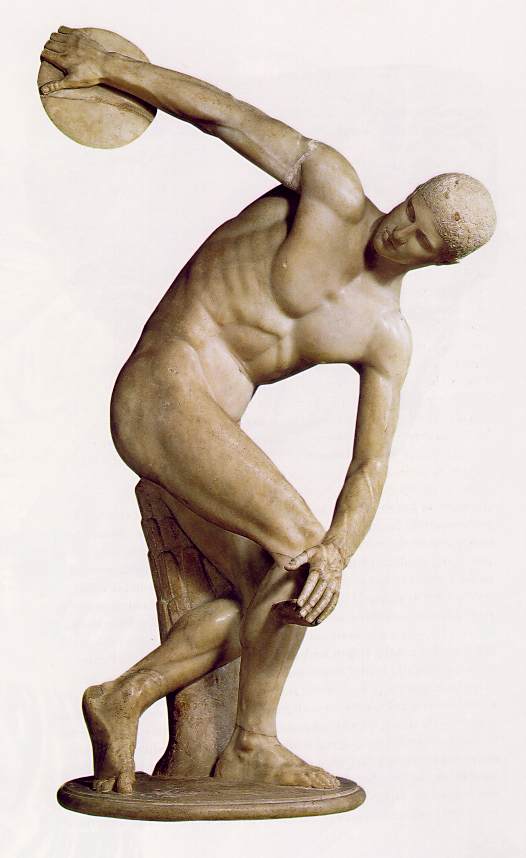

The Phaiakians have other Olympic sports as well:

Then they made room for wrestling—grinding bouts

that Seareach won, pinning the strongest men;

then the broad jump; first place went to Seabelt;

Sparwood gave the discus the mightiest fling,

and Prince Laodamas outboxed them all.

At this point the prince turns to Odysseus, who has just survived drowning and so is not exactly in shape. When one of the contestants baits him, however, the Ithacan king has to prove his mettle. I thought of this moment when American athlete Valarie Allman won her second straight Olympic gold medal in the discus:

[Odysseus] leapt out, cloaked as he was, and picked a discus,

a rounded stone, more ponderous than those

already used by the Phaiakian throwers,

and, whirling, let it fly from his great hand

with a low hum. The crowd went flat on the ground

all those oar-pulling, seafaring Phaiakians—

under the rushing noise. The spinning disk

soared out, fight as a bird, beyond all others.

Disguised now as a Phaiakian,

Athena staked it and called out:

“Even a blind man,

friend, could judge this, finding with his fingers

one discus, quite alone, beyond the cluster.

Congratulations; this event is yours;

not a man here can beat you or come near you.”

I wonder whether, following a successful contest, the gold-medal athletes feel as though a god is announcing their victory. Athena’s words certainly apply to that magnificent pole vault.