Tuesday

Reader and friend Valerie Hotchkiss, and of last month Oberlin’s new librarian, alerted me to an article about librarians providing aid and comfort to wounded soldiers in World War I. While the soldiers often gravitated to predictable works—”Periods of Zane Greyism will be followed by feverish cravings for ‘Tarzanry,’” one librarian reported—librarians were startled by the popularity of romance novels.

The article in Lady Science reports,

In a paper delivered before peers at the ALA conference in 1918, hospital librarian Miriam Carey examined the appeal of love stories to men who suffered from homesickness in particular. “What does a home-sick man choose for his reading?” she wondered. “Probably what he secretly craves is an old-fashioned love story and the librarian always takes a few with her although,” she noted, “at the outset she did not expect to find much call for such books.” Carey was not alone in expressing surprise at the request for love stories. “Yesterday a man said, ‘Give me a real love story,’” one librarian reported. “All the men laughed, but when I went to their beds, most of them said, ‘I want one like that other fellow asked for.’”

The desire for love stories actually worried some of the librarians, who saw it undermining the masculinity that believed was required to fight:

Carey theorized that her patients’ desire for love stories stemmed from the tendency of illness to feminize. “Human nature is very much the same everywhere,” she noted, “and the man who is sick is more like his mother than his father.” This may suggest that in gravitating to romances the patient desired the comfort of women and femininity.

Carey reassured people that “this state of mind is, however, fleeting” and that “the home-sick man will be wanting western yarns and other former favorites very soon.”

Another way to read this preference, however, is that love seemed the most important thing at the moment. Certainly more important than an egotistical triumph over another man.

I’m interested in some of the other books requested. According to the librarians of the time, these included “Ivanhoe, Waverly, and Oliver Twist alongside O. Henry, Conan Doyle, and other ‘red-blooded fiction-detective stories and adventure stories.’” Some of these, I suspect, have less to do with being red-blooded than being familiar, a reminder of more innocent times. Oliver Twist is hardly a macho story.

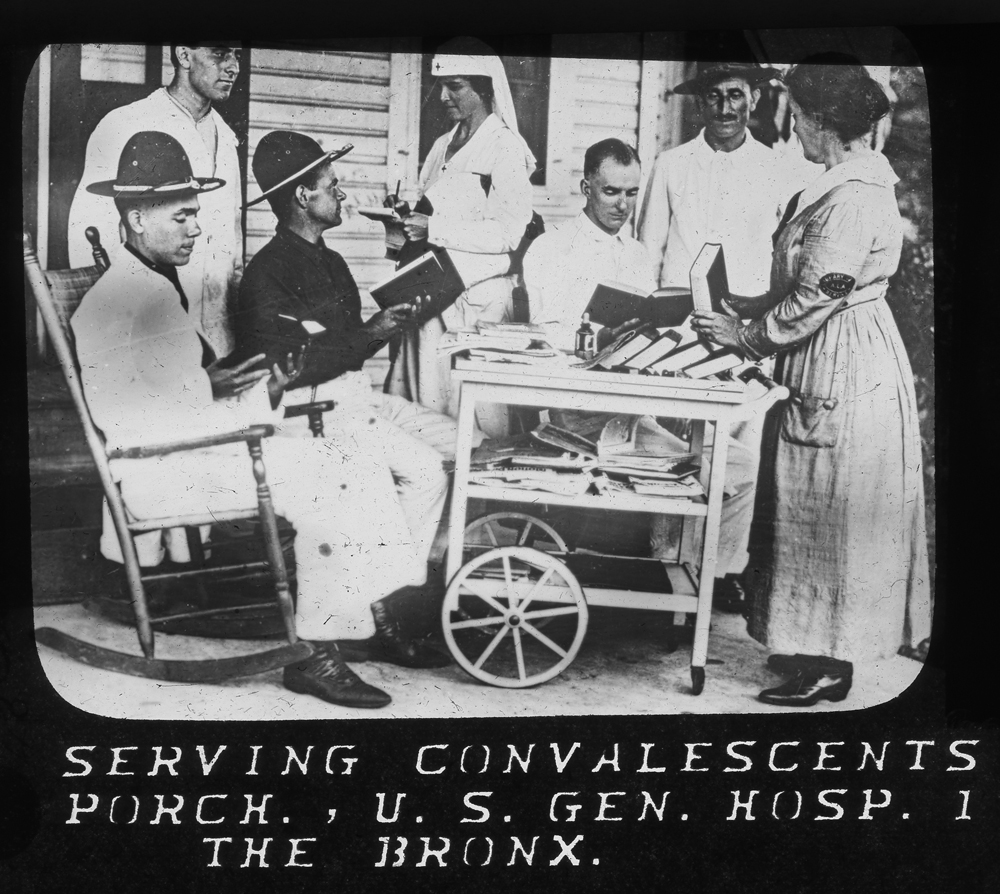

Interested in healing the sick, the doctors proved to be forward thinking in their belief that literature could play a significant role. Apparently there are many American Library Association publicity photos of “hospital librarians on daily rounds dispensing literary cures to patients’ bedsides.” The article says that “they believed fiction offered great therapeutic value” and that “sometimes stories are better than doctors.”

And yet librarians also discovered the limitations of bibliotherapy, at least when compared to other forms of treatment. As I know well from my own experience, one never knows which books will elicit which reactions. As one librarian wrote at the time,

a novel with a happy ending is not necessarily a stimulant to the depressed patient, who may be tempted to contrast his own wretched state with that of the happy hero. Nor is every tragedy a depressant. A serious book may prove to be better reading for a nervous patient than something in a lighter vein – he may get new courage and a firm resolve to be master of his fate and by reading of another’s struggle against adverse circumstances.”

This is why we need to read many books. We may not be able to predict ahead of time which work each of us needs, but the more we read, the more we are likely to find just the right book for us.