Monday

I’ve hesitated weighing in on the Dr. Seuss controversy—or rather, manufactured controversy—because I consider it a Republican attempt to sidetrack the country into culture wars following their failure to address the pandemic and economic crisis. Since this is a literary blog, however, I should weigh in given that there are some legitimate issues involved.

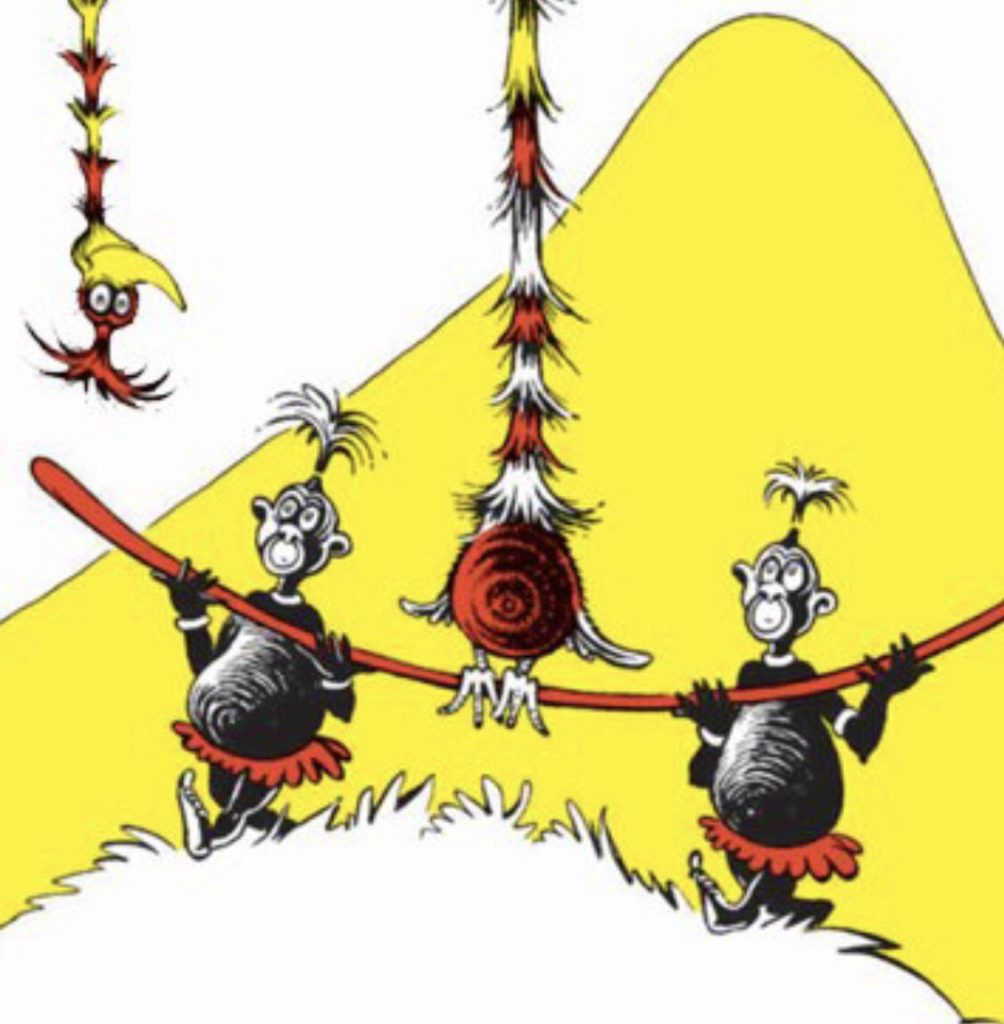

First, however, let’s note that the political argument is in bad faith since conservatives, after gesturing towards the publisher’s withdrawal of six titles, immediately go to Green Eggs and Ham, which is not one of the titles being “canceled.” The withdrawn titles, incidentally, are so obscure that even I, a huge Dr. Seuss fan, have never heard of them (well, except for To Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street). For those who haven’t been following the news, the other titles are If I Ran the Zoo, Scrambled Eggs Super, McElligot’s Pool, The Cat’s Quizzer, and On Beyond Zebra! You can go here to see the caricatures of Asians, Africans, and Inuits that prompted the publisher to withdraw the books. I haven’t heard a single rightwing defense of any of them.

As for Dr. Seuss’s other books, Cat in the Hat, The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, Horton Hears a Who, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish, Marvin K. Mooney Will You Please Go Now, Hop on Pop, and Fox in Sox are not being withdrawn. Nor are The Lorax, about corporate devastation of the environment, and The Butter Battle Book, about an unfettered arms race—books which, I notice, never get mentioned by conservative commentators. And which party just, grinch-like, voted unanimously against pandemic aid after years of pushing wealth towards the top one percent?

What are we to make of the publisher’s decision? They’re doing what publishers have been doing for centuries, given that tastes change and what is inoffensive to one generation shocks another. I first became aware of this at 13 when I searched all over Paris for one of the first Tintin books. Tintin au Congo has such cringe-worthy depictions of Africans (often as children grateful for a white savior) that even in 1965 one couldn’t find it in print, and I had to scour used book stores to find a copy. Sometimes authors themselves will revise their works, as Mary Travers did with the depiction of an African tribesman in one of her Mary Poppins books. I suspect that, were he still alive, Seuss, a Roosevelt Democrat, would have changed the image of the China man with chopsticks (and wearing Japanese shoes) in Mulberry Street (1937).

Conservatives don’t talk about how such depictions can do harm. The same kind of reductionism in racist caricatures is also at work in the present rise of anti-Asian violence, which is partly due to Covid although it has always been with us. Distinctions are not made between Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese, Laotian, and other East Asian groups, and I dread the day when my biologically half-Korean grandson encounters such prejudice. For all the right wing’s talk about cancelation culture, they never acknowledge how they themselves cancel individual identities with their racial stereotyping. In fact, stereotyping is the ultimate form of cancelation.

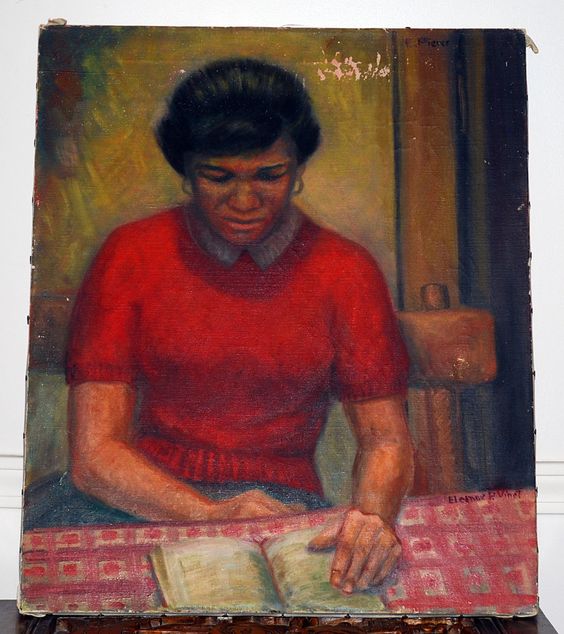

This is the point made by one Michael Harriot, an African American, in an extended twitter thread that is so rich that I will quote it at length. Harriot says rightwing obsession over Dr. Seuss has taken him back to “the second-most devastating day of my life,” which was when “I found out the Hardy Boys were white.”

Harriot didn’t discover this earlier, he says, because his mother, who home schooled him until he was 12, built a “white people-free cocoon” around him and his sisters. She did so because she believed that Black children cannot “fully realize[ ] their humanity in the presence of whiteness.” When it comes to reading, the problem is that white readers have many characters to identify with while Black readers are stuck with a stereotype here or there. As Harriot puts it,

The few representations of Black people on TV and in books were WHITE PEOPLE’S versions of us. Not necessarily negative as much as they are stratified…Sassy or subservient. Poor or lucky. The criminal or the hero. Our existence is defined by how white people see us.

And

[Whites] don’t realize that the only time a Black child saw themselves in a Seuss book was in a racist illustration. They can’t comprehend because, even if there’s one bad characterization of whiteness, there are one hundred other characters in the book. Even when the villain in the TV show is white, so is the hero…And the hero’s sidekick…And the lawyer..And the cop…And judge…And the anchor on the news…And the weatherman…And the QB…And the commentator…And everyone except the ONE Black person

The point is: THEY GET TO CHOOSE!

To counter this, Harriot’s mother manufactured “a bizarro world where white people were the minority, they did not control the narrative and Black was the default.” Harriot lays out the lengths she went to and how much work it took:

When my sisters and I were really young, she would read bedtime stories. But she would change all the names. When she worked at night, she recorded cassettes of her reading for us to fall asleep to.

She even removed covers from books with white kids on the cover. We also couldn’t watch reruns of Sanford & Son, The Jeffersons or Good Times until we were older.

Harriot says that, while he knew that “white people were a thing,” he adds,

But if you had asked eight-year-old me, I would have told you that MOST people were Black.

And so, never having seen them, I assumed the Hardy Boys were 2 niggas from the suburbs of Detroit. Same with Encyclopedia Brown. Black was my default.

Looking back, he’s impressed with the results:

I honestly believe that the reason a lot of white people think I’m “the real racist” is because I never learned how to care what white people think. There is a subtle, subconscious deference to whiteness that MOST of us have.

My Trinidadian daughter-in-law would relate: she talks about not realizing that skin color was a thing when growing up because everyone looked like her. It became an issue only when she moved to the United States. While not as totalizing at Harriot’s mother, she and my son are very attuned to the books, television shows, and movies their children consume. They know, as Harriot’s mother knew, about white cancelation culture.

I can think of two black authors who push back as Harriot’s mother did, creating mostly Black worlds where their characters are not defined by whiteness. Whites sometimes put in an appearance in Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, but for the most part they seem irrelevant. Toni Morrison too creates an all-Black world in Paradise, where characters have the freedom to develop their own identities, sometimes for good, sometime for ill. The point is, there is not an all-powerful white presence calling the shots.

So why are conservatives up in arms about cancel culture? Because they don’t like the unaccustomed pushback they are getting when they try to cancel others. Their cancel culture complaints reflect their longing for a society where whites are still calling the shots.