Monday

I am pleased to report that the issues with my blog have been resolved (all hail to GoDaddy!) and I am catching up on back posts. I’m currently listening to Virginia Woolf’s Voyage Out, one of the few novels of hers I have not read, and am particularly enjoying Rachel, a young woman and accomplished pianist who has been cut off from the world. I especially like watching her growth through literature.

Rachel’s mother having died, she has been alternating between an isolated life with two maiden aunts and an equally isolated life onboard ship with her father, who owns a shipping company. Fortunately, she meets up with Helen Ambrose on the boat, who invites her to stay with her at a resort on the South American coast and who introduces her to books:

Among the promises which Mrs. Ambrose had made her niece should she stay was a room cut off from the rest of the house, large, private—a room in which she could play, read, think, defy the world, a fortress as well as a sanctuary. Rooms, she knew, became more like worlds than rooms at the age of twenty-four. Her judgment was correct, and when she shut the door Rachel entered an enchanted place, where the poets sang and things fell into their right proportions.

The plays of Heinrik Ibsen especially fascinate her. From a reference to Nora, it appears that she has just been reading The Doll’s House, about a wife who rebels against being treated like a child. The other book mentioned is George Meredith’s Diana of the Crossroads, which according to Wikipedia is about “an intelligent and forceful woman trapped in a miserable marriage.” One can see why Rachel becomes thoughtful:

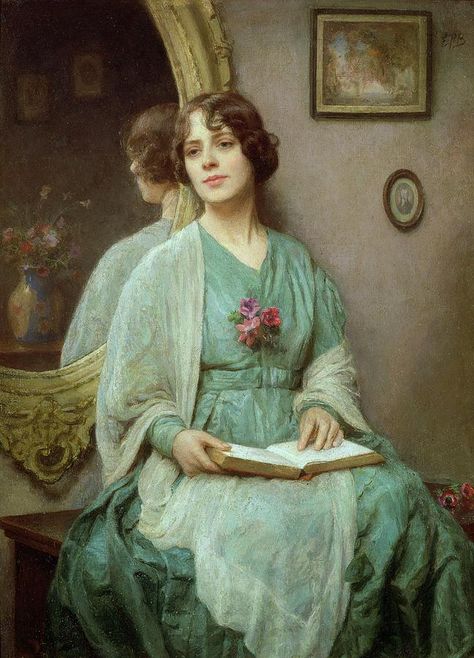

Far from looking bored or absent-minded, her eyes were concentrated almost sternly upon the page, and from her breathing, which was slow but repressed, it could be seen that her whole body was constrained by the working of her mind. At last she shut the book sharply, lay back, and drew a deep breath, expressive of the wonder which always marks the transition from the imaginary world to the real world.

“What I want to know,” she said aloud, “is this: What is the truth? What’s the truth of it all?” She was speaking partly as herself, and partly as the heroine of the play she had just read. The landscape outside, because she had seen nothing but print for the space of two hours, now appeared amazingly solid and clear, but although there were men on the hill washing the trunks of olive trees with a white liquid, for the moment she herself was the most vivid thing in it—an heroic statue in the middle of the foreground, dominating the view.

Helen, who is a sensitive soul, figures that substantive identity exploration is underway:

Ibsen’s plays always left [Rachel] in that condition. She acted them for days at a time, greatly to Helen’s amusement; and then it would be Meredith’s turn and she became Diana of the Crossways. But Helen was aware that it was not all acting, and that some sort of change was taking place in the human being. When Rachel became tired of the rigidity of her pose on the back of the chair, she turned round, slid comfortably down into it, and gazed out over the furniture through the window opposite which opened on the garden. (Her mind wandered away from Nora, but she went on thinking of things that the book suggested to her, of women and life.)

Helen, like a good teacher when the pupil is eager to learn, knows enough to stay out of the way:

During the three months she had been here she had made up considerably, as Helen meant she should, for time spent in interminable walks round sheltered gardens, and the household gossip of her aunts. But Mrs. Ambrose would have been the first to disclaim any influence, or indeed any belief that to influence was within her power. She saw her less shy, and less serious, which was all to the good, and the violent leaps and the interminable mazes which had led to that result were usually not even guessed at by her. Talk was the medicine she trusted to, talk about everything, talk that was free, unguarded, and as candid as a habit of talking with men made natural in her own case.

Woolf also notes that Helen does not want Rachel to become an angel of the house (or a Nora), sacrificing her own needs so that men will find her amiable:

Nor did she encourage those habits of unselfishness and amiability founded upon insincerity which are put at so high a value in mixed households of men and women. She desired that Rachel should think, and for this reason offered books and discouraged too entire a dependence upon Bach and Beethoven and Wagner.

Whereas Helen’s tastes run more to social drama, however, Rachel appears more drawn to psychodrama. Again, Helen knows enough to stay out of the way:

But when Mrs. Ambrose would have suggested Defoe, Maupassant, or some spacious chronicle of family life, Rachel chose modern books, books in shiny yellow covers, books with a great deal of gilding on the back, which were tokens in her aunt’s eyes of harsh wrangling and disputes about facts which had no such importance as the moderns claimed for them. But she did not interfere. Rachel read what she chose, reading with the curious literalness of one to whom written sentences are unfamiliar, and handling words as though they were made of wood, separately of great importance, and possessed of shapes like tables or chairs. In this way she came to conclusions, which had to be remodeled according to the adventures of the day, and were indeed recast as liberally as anyone could desire, leaving always a small grain of belief behind them.

Literature’s power to influence character should never be underestimated. When I complete the novel, I’ll report on how Rachel turns out.