Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Sunday

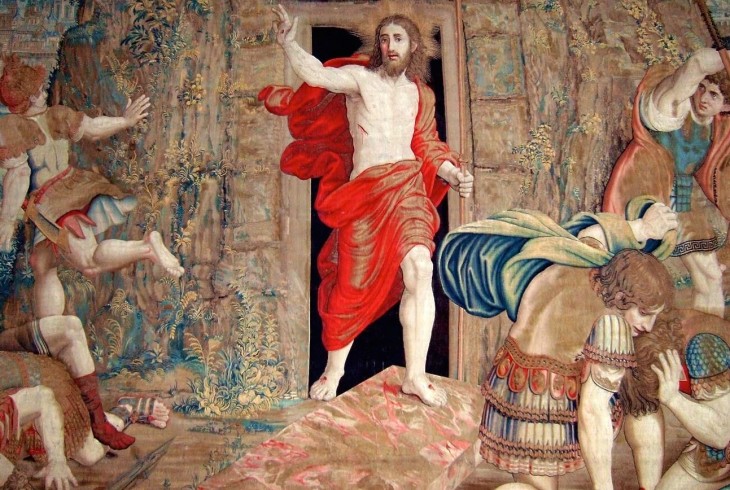

A month ago I shared a talk given by Sewanee English professor Jennifer Michael on poems that help us imagine ourselves in the scriptures. In “Descending Theology: The Resurrection,” Mary Karr puts herself in the mind of the recently crucified Jesus, longing for the physicality of flesh even when that physicality involves pain.

It is a version of the theology that believes that God became incarnate in Jesus because God wanted to experience what it’s like to be human. In a talk I once gave on literary angels I noted that, in Philip Pullman’s vision, angels don’t glory in their immateriality but rather long for immersion in the world of the senses. Kerr refers to such longing in her poem:

From the far star points of his pinned extremities,

cold inched in—black ice and squid ink—

till the hung flesh was empty.

Lonely in that void even for pain,

he missed his splintered feet,

the human stare buried in his face.

He ached for two hands made of meat

he could reach to the end of.

In the corpse’s core, the stone fist

of his heart began to bang

on the stiff chest’s door, and breath spilled

back into that battered shape. Now

it’s your limbs he comes to fill, as warm water

shatters at birth, rivering every way.

I love the birth imagery here. As in T.S. Eliot’s Waste Land or George Herbert’s “Altar,” there is something stiff and hard resisting new life, something that breaks wide open at the resurrection. New hope rivers every way.