Spiritual Sunday

Today’s Gospel passage is one that Jane Eyre turns to unwillingly at a major crisis point in her life. Jesus, playing the tough coach, gives his disciples difficult advice that they too don’t want to hear. Both the disciples and Jane need Jesus’s tough language, however, if they are to move past self and into love.

In the passage from Mark (9:38-50), Jesus catches his disciples behaving territorially. A stranger has been casting out devils in Jesus’s name, and the disciples think he is claiming spoils that they regard as rightfully theirs:

John said to Jesus, “Teacher, we saw someone casting out demons in your name, and we tried to stop him, because he was not following us.” But Jesus said, “Do not stop him; for no one who does a deed of power in my name will be able soon afterward to speak evil of me. Whoever is not against us is for us. For truly I tell you, whoever gives you a cup of water to drink because you bear the name of Christ will by no means lose the reward.

Concerned that his disciples won’t hear what he is saying, Jesus resorts to violent images:

If any of you put a stumbling block before one of these little ones who believe in me, it would be better for you if a great millstone were hung around your neck and you were thrown into the sea. If your hand causes you to stumble, cut it off; it is better for you to enter life maimed than to have two hands and to go to hell, to the unquenchable fire. And if your foot causes you to stumble, cut it off; it is better for you to enter life lame than to have two feet and to be thrown into hell. And if your eye causes you to stumble, tear it out; it is better for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye than to have two eyes and to be thrown into hell, where their worm never dies, and the fire is never quenched.

The disciples focus more on their own egos than on the love of God, and abandoning such pride can seem comparable to cutting off a hand or plucking out an eye. Our narcissism plunges us into an internal hell because it separates us from the divine. Jesus feels that he can’t make this point strongly enough.

Jane recalls the passage at a moment when she is in shock. She has just discovered that Rochester is already married and that she is about to experience once again her life of solitude and self doubt:

Some time in the afternoon I raised my head, and looking round and seeing the western sun gilding the sign of its decline on the wall, I asked, “What am I to do?”

But the answer my mind gave—“Leave Thornfield at once”—was so prompt, so dread, that I stopped my ears. I said I could not bear such words now. “That I am not Edward Rochester’s bride is the least part of my woe,” I alleged: “that I have wakened out of most glorious dreams, and found them all void and vain, is a horror I could bear and master; but that I must leave him decidedly, instantly, entirely, is intolerable. I cannot do it.”

But, then, a voice within me averred that I could do it and foretold that I should do it. I wrestled with my own resolution: I wanted to be weak that I might avoid the awful passage of further suffering I saw laid out for me; and Conscience, turned tyrant, held Passion by the throat, told her tauntingly, she had yet but dipped her dainty foot in the slough, and swore that with that arm of iron he would thrust her down to unsounded depths of agony.

“Let me be torn away,” then I cried. “Let another help me!”

“No; you shall tear yourself away, none shall help you: you shall yourself pluck out your right eye; yourself cut off your right hand: your heart shall be the victim, and you the priest to transfix it.”

I rose up suddenly, terror-struck at the solitude which so ruthless a judge haunted,—at the silence which so awful a voice filled.

Perhaps such tough coaching is what Jane needs if she is to be strong. She has all but turned Rochester into her idol and is in danger of succumbing to his seductive temptation, which is to become his mistress in France. If she were to give in, she would be tormented for the rest of her life.

Jesus is about much more than renouncing, however. Above all, he wants us to love. Later, when Jane is wrestling with an equally difficult decision, she again hears a voice calling out to her. This time, however, she is told to follow a sweeter path than the austere duty that St. John Rivers insists on. The moment occurs when she is on the verge of agreeing to become his wife and travel with him to India:

“Show me, show me the path!” I entreated of Heaven. I was excited more than I had ever been; and whether what followed was the effect of excitement the reader shall judge.

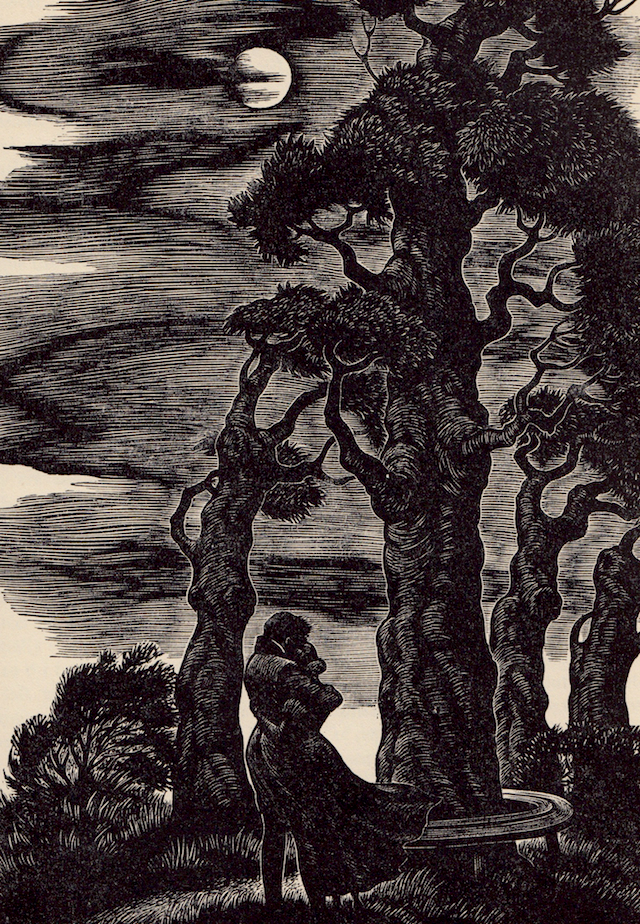

All the house was still; for I believe all, except St. John and myself, were now retired to rest. The one candle was dying out: the room was full of moonlight. My heart beat fast and thick: I heard its throb. Suddenly it stood still to an inexpressible feeling that thrilled it through, and passed at once to my head and extremities. The feeling was not like an electric shock, but it was quite as sharp, as strange, as startling: it acted on my senses as if their utmost activity hitherto had been but torpor, from which they were now summoned and forced to wake. They rose expectant: eye and ear waited while the flesh quivered on my bones.

“What have you heard? What do you see?” asked St. John. I saw nothing, but I heard a voice somewhere cry—

“Jane! Jane! Jane!”—nothing more.

“O God! what is it?” I gasped.

I might have said, “Where is it?” for it did not seem in the room—nor in the house—nor in the garden; it did not come out of the air—nor from under the earth—nor from overhead. I had heard it—where, or whence, for ever impossible to know! And it was the voice of a human being—a known, loved, well-remembered voice—that of Edward Fairfax Rochester; and it spoke in pain and woe, wildly, eerily, urgently.

“I am coming!” I cried. “Wait for me! Oh, I will come!”

If the first call demands that Jane break with Rochester, the second urges her to return to him. She has developed a much stronger sense of self—her self-discipline helped her get there—and now she can follow her heart:

I broke from St. John, who had followed, and would have detained me. It was my time to assume ascendency. My powers were in play and in force. I told him to forbear question or remark; I desired him to leave me: I must and would be alone. He obeyed at once. Where there is energy to command well enough, obedience never fails. I mounted to my chamber; locked myself in; fell on my knees; and prayed in my way—a different way to St. John’s, but effective in its own fashion. I seemed to penetrate very near a Mighty Spirit; and my soul rushed out in gratitude at His feet. I rose from the thanksgiving—took a resolve—and lay down, unscared, enlightened—eager but for the daylight.

Jesus doesn’t demand discipline from us merely for the sake of discipline. If we see that discipline as an end in itself, as St. John appears to do, we become dry and brittle. Sometimes it is equally difficult to open ourselves to the love that Jesus wants us to experience. That is the Mighty Spirit that calls Jane and to which she responds.

Previous posts on spiritual questing in Jane Eyre