Tuesday

I am so deeply ensconced in revising my book Does Literature Make Us Better People? that I’m having difficulty breaking free to write my regular daily essays. Today, therefore, you get another of the many short chapters from the book. The chapter on Samuel Johnson follows chapters on Plato, Aristotle, Horace, and Sir Philip Sidney. Enjoy yourself while I return back to my chapters on Marx and Freud.

Although middle class readership skyrocketed in 18th century Britain, not all of the new encounters with print were seen as beneficial. As in previous eras, there were concerns about literature leading young people astray. And not only young people. Scholar J. Paul Hunter, my dissertation director, recounts how husbands were unnerved when their wives would disappear for days into Samuel Richardson’s million-word melodrama Clarissa, neglecting household duties and other responsibilities.

Given how we ourselves have been thrown off stride by globalization and social media, we can relate to what the British were undergoing at the time. The country was rapidly changing from a landed to a mercantile society, with power shifting from the gentry to the middle class. International trade and technical innovations were ushering in a new prosperity that was at once exhilarating and disorienting. A need arose for social observers who could guide parents and the public generally through this confusing morass.

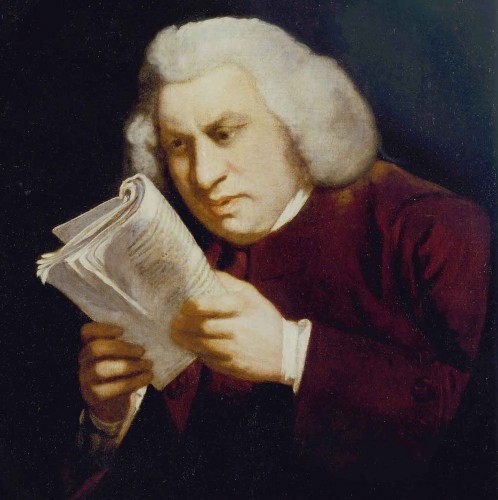

Into that vacuum strode Samuel Johnson (1709-84), who was there to (among other things) teach people how to read correctly, what to do with what they read, and what to avoid. As Johnson saw it, Shakespeare was must reading because he shows us the truth of our condition. Comedies of romance, on the other hand, tickle our baser instincts and should be shunned.

The last third of the 18th century is sometimes known as “the Age of Johnson” and it’s not hard to see why. A man of vast intelligence, Johnson, working virtually alone, created the first comprehensive English dictionary, an achievement that (in the words of biographer Walter Jackson Bate) “easily ranks as one of the greatest single achievements of scholarship.” Johnson was also the author of a magnificent long poem (“The Vanity of Human Wishes”), a dazzling philosophical novel (The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia), a important critical edition of Shakespeare, an in-depth survey of England’s contemporary poets, and two sets of groundbreaking essays (the Rambler essays, published twice a week from 1750-52, and the Idler essays, published weekly from 1758-60). In addition, he presided over regular gatherings of the leading lights of the day. Meeting with him in coffee houses and over bowls of rum punch to discuss everything from art to science to politics were figures like painter Joshua Reynolds, actor David Garrick, political theorist Edmund Burke, historian Edward Gibbon (The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire), author Oliver Goldsmith (Vicar of Wakefield, She Stoops to Conquer), and James Boswell, whose account of Johnson’s life is one of the world’s great biographies.

According to Bate, Johnson considered himself above all as a moralist. Whether he was a Tory conservative is another matter as Bate says he is more complicated than such a label suggests. Johnson was certainly suspicious of grandiose claims of progress being made by the mercantile classes, not to mention by America’s founding fathers. He was well aware of how humans fall short of their ideals and so was unwilling to jettison time-honored traditions, including class hierarchy and colonial rule. His Shakespearean dedication to capturing the truth about human beings, however, led him to reject facile political bromides from any party. People cannot be reduced to ideological pigeonholes.

Echoing Aristotle, Johnson believes the poet, in contrast to the historian, expresses the universal rather than the particular. As he sees it, no modern poet does this better than Shakespeare. In his “Preface to Shakespeare,” which Bates describes as “one of the landmarks in the history of literary criticism,” Johnson tells us, to operate more effectively in the world, we must read Shakespeare:

Shakespeare is above all writers, at least above all modern writers, the poet of nature; the poet that holds up to his readers a faithful mirror of manners and of life…His persons act and speak by the influence of those general passions and principles by which all minds are agitated, and the whole system of life is continued in motion. In the writings of other poets a character is too often an individual; in those of Shakespeare it is commonly a species.

In Johnson’s formulation, Shakespeare is a rich treasure trove that is to be mined for his salutary insights. Quoting Horace that “the end of poetry is to instruct by pleasing,” Johnson says that Shakespeare’s plays provide “much instruction”:

It is from this wide extension of design that so much instruction is derived. It is this which fills the plays of Shakespeare with practical axioms and domestic wisdom. It was said of Euripides, that every verse was a precept; and it may be said of Shakespeare, that from his works may be collected a system of civil and economical prudence.

Like Aristotle, Johnson thinks that literature’s profound understanding of human nature will provide moral guidance. Or as he says of Shakespeare later in the preface, “From his writings indeed a system of social duty may be selected.”

Drama doesn’t offer up axioms and systems the way that a text of moral philosophy does, however, and Johnson instructs us not to look at individual quotes. The real wisdom comes from what is communicated through the unfolding of the stories and through dialogue:

Yet his real power is not shown in the splendor of particular passages, but by the progress of his fable, and, the tenor of his dialogue; and he that tries to recommend him by select quotations, will succeed like the pedant in Hierocles, who, when he offered his house to sale, carried a brick in his pocket as a specimen.

In other words, don’t quote Polonius’s “to thine own self be true” advice to Laertes if you want to do justice to Shakespeare’s insights. Rather, watch how Polonius and Laertes and Hamlet and others respond to the pressures of the moment and how they talk to others. Johnson could well have Aristotle’s observation in mind—that a tragedian knows how a person will speak or act “according to the law of probability or necessity”— when he writes,

Shakespeare has no heroes; his scenes are occupied only by men, who act and speak as the reader thinks that he should himself have spoken or acted on the same occasion: Even where the agency is supernatural the dialogue is level with life… Shakespeare approximates the remote, and familiarizes the wonderful; the event which he represents will not happen, but if it were possible, its effects would be probably such as he has assigned; and it may be said, that he has not only shown human nature as it acts in real exigencies, but as it would be found in trials, to which it cannot be exposed.

According to Johnson, by reading Shakespeare’s “human sentiments in human language,” a hermit would be able to figure out what is going on in the world and a confessor would be able to predict where the human passions will lead. Figuring out such things will, in turn, allow us to operate more effectively in the world.

Something altogether different happens when one reads a novel like Tom Jones, however,especially if one is a young person. Johnson may sound like Aristotle when discussing Shakespeare, but when it comes to teens reading “comedies of romance” he sounds like Plato worrying that military auxiliaries will be corrupted by Homeric accounts of misbehaving gods and goddesses. These novels, Johnson says, target

the young, the ignorant, and the idle, to whom they serve as lectures of conduct, and introductions into life. They are the entertainment of minds unfurnished with ideas, and therefore easily susceptible of impressions; not fixed by principles, and therefore easily following the current of fancy; not informed by experience, and consequently open to every false suggestion and partial account.

The danger, Johnson says, is that young people are eager to learn by imitation (Aristotle), so that when they choose bad models, they will turn out badly.

Johnson makes one distinction that doesn’t hold up: he thinks that young people will be more swayed by realistic than by fantasy fiction, whereas we know that conservative parents today worry equally about their children reading the realism of Judy Blume and the fantasy of J. K. Rowling. Otherwise, however, Johnson’s observations about the imitation process have a point:

But when an adventurer is leveled with the rest of the world, and acts in such scenes of the universal drama, as may be the lot of any other man; young spectators fix their eyes upon him with closer attention, and hope, by observing his behavior and success, to regulate their own practices, when they shall be engaged in the like part.

Given this psychological truth, Johnson says that parents and society’s moral guardians must intervene to protect young people from dangerous content. Citing Horace’s concerns about young people, he writes that “nothing indecent should be suffered to approach their eyes or ears.” Parents must exercise caution in everything that is laid before young people in order “to secure them from unjust prejudices, perverse opinions, and incongruous combinations of images.”

Literature is particularly dangerous because it is so insidious. Johnson fears that dubious fictional characters will “take possession of the memory by a kind of violence, and produce effects almost without the intervention of the will.” Once again, because of fiction’s power, “the best examples only should be exhibited…”

Johnson is not entirely adverse to readers’ minds being so seized—he is different from Plato in this regard—and indeed, like Horace and Sidney, he sees the delight we get from literature as a powerful tool to inculcate virtue. For instance, he describes Richardson’s Clarissa, where one cries for the virtuous heroine when she dies following her escape from her abductor and rapist, as “the first book in the world for the knowledge it displays of the human heart.” The right tools are needed if the right ends are to be achieved, however.

Unfortunately, he believes that the realistic comedies of romance of the time will lead young people astray. When Johnson writes about novels that corrupt, his leading culprit is Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, a runaway sensation among the young the previous year. That Fielding gives his hard-drinking, hard-loving protagonist a good heart and a noble spirit makes the novel all the more dangerous in Johnson’s eyes:

Many writers, for the sake of following nature, so mingle good and bad qualities in their principal personages, that they are both equally conspicuous; and as we accompany them through their adventures with delight, and are led by degrees to interest ourselves in their favor, we lose the abhorrence of their faults, because they do not hinder our pleasure, or, perhaps, regard them with some kindness, for being united with so much merit.”

In other words, Tom’s good qualities lure us into overlooking his faults. We may lose our abhorrence of drinking and womanizing.

Johnson is not entirely consistent here. What he says about characters like Tom could just as easily be said about Shakespeare’s Prince Hal, whose depiction Johnson praises. Johnson’s inconsistency may lie in fears about how the young people of his day were gripped by novels as they were not by Shakespeare. As always, when the young become engrossed in fictional worlds, their elders become concerned.