Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Thursday

In a conversation I had last week with author Maggie Thrash, I learned that dystopian science fiction, long a bestselling genre, is less popular these days. The major reason makes sense. Why read dark warnings about the future when the future is here, when George Orwell’s 1984 appears to be an operations manual for the current administration and Handmaid’s Tale is a step away from becoming reality?

I mention this latter example in light of terrifying developments regarding female reproduction. I recommend subscribing to Jessica Valenti’s free substack blog Abortion, Every Day if you want a full rundown. There you can read about women being arrested for miscarriages, Texas midwives being charged with felonies, and pregnant women dying of sepsis when they could have received life-saving abortions. The situation worsens by the day.

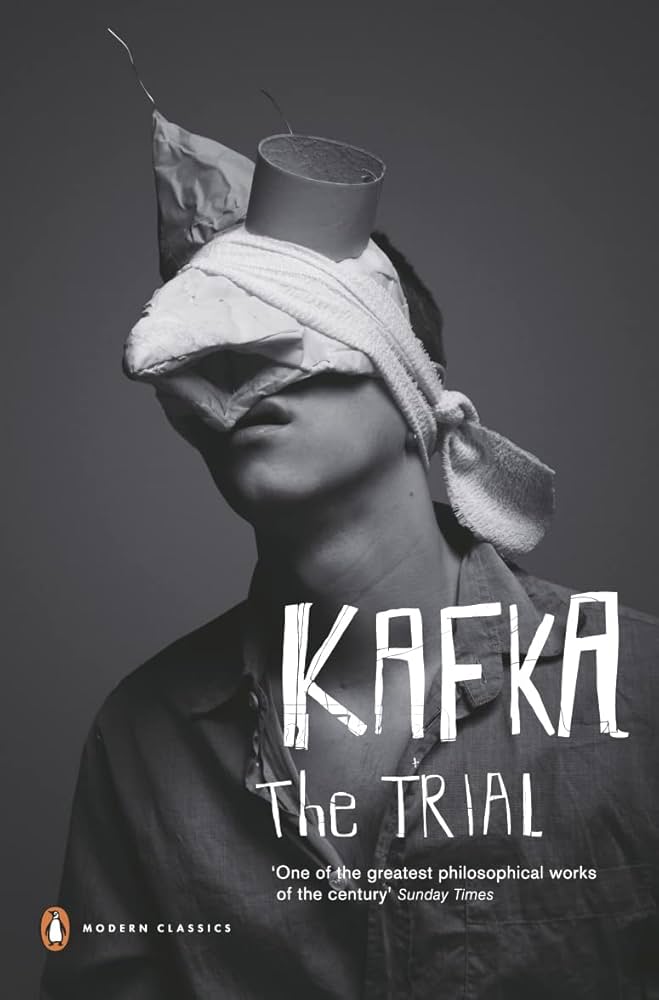

In today’s post, however, I want to focus on those people who are being disappeared, a development reminiscent of Kafka’s Trial. The Guardian has an account of a Canadian entrepreneur who, for two weeks, found herself in ICE custody and then two private prisons after she entered the country legally. Fortunately Jasmine Mooney, as she notes in the article, is one of the lucky ones, thanks to various support systems she could draw on.

Others have not been so fortunate. Many of the Venezuelans sent to the notorious El Salvador prison have little legal recourse, even though they are not in fact gang members (apparently ICE has been misinterpreting their tattoos). These misidentifications haven’t prevented the State Department under Marco Rubio from cheering their horrific treatment. The U.S., it appears, is several steps into our version of Pastor Martin Niemöller’s famous poem, “First they came for the communists.”

At the very end of Kafka’s Trial, we watch as K is disappeared. I won’t get into K’s psychological drama here, how he’s so beaten down that he practically accedes to his execution. Rather, I focus on the fact that he’s innocent of all wrongdoing. For no reason at all—certainly no reason that anyone in the book gives—he has been singled out to be killed.

In a scenario that is becoming increasingly common in the States, two men show up at K’s door and, without any explanation, escort him out:

[T]hey took his arms in a way that K. had never experienced before. They kept their shoulders close behind his, did not turn their arms in but twisted them around the entire length of K.’s arms and took hold of his hands with a grasp that was formal, experienced and could not be resisted. K. was held stiff and upright between them, they formed now a single unit so that if any one of them had been knocked down all of them must have fallen. They formed a unit of the sort that normally can be formed only by matter that is lifeless.

The men escort K to an abandoned quarry, where they prepare for the execution:

After exchanging a few courtesies about who was to carry out the next tasks—the gentlemen did not seem to have been allocated specific functions—one of them went to K. and took his coat, his waistcoat, and finally his shirt off him….[Then he took him under the arm and walked up and down with him a little way while the other gentleman looked round the quarry for a suitable place. When he had found it he made a sign and the other gentleman escorted him there. It was near the rockface, there was a stone lying there that had broken loose. The gentlemen sat K. down on the ground, leant him against the stone and settled his head down on the top of it….Then one of the gentlemen opened his frock coat and from a sheath hanging on a belt stretched across his waistcoat he withdrew a long, thin, double-edged butcher’s knife which he held up in the light to test its sharpness. The repulsive courtesies began once again, one of them passed the knife over K. to the other, who then passed it back over K. to the first. K. now knew it would be his duty to take the knife as it passed from hand to hand above him and thrust it into himself. But he did not do it, instead he twisted his neck, which was still free, and looked around. He was not able to show his full worth, was not able to take all the work from the official bodies, he lacked the rest of the strength he needed and this final shortcoming was the fault of whoever had denied it to him.

And finally this:

But the hands of one of the gentleman were laid on K.’s throat, while the other pushed the knife deep into his heart and twisted it there, twice. As his eyesight failed, K. saw the two gentlemen cheek by cheek, close in front of his face, watching the result. “Like a dog!” he said, it was as if the shame of it should outlive him.

The “like a dog” thought points to how he has been stripped of his humanity and reduced to such a state that he sees himself as an animal. When a society starts descending to that level, we are in Nazi territory. Throughout the novel, K has attempted to do everything society has instructed him to, only to end up here. The allegorical “K” stands for all of us.

America has become Amerika.