Wednesday

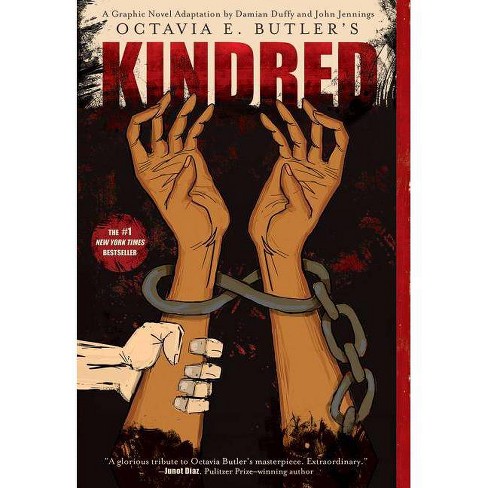

I see that Hulu has come up with an eight-part series based on Octavia Butler’s Kindred (1979), a powerful work I used to teach in my American Fantasy class. I share today a post I wrote about the novel six years ago. But first, here are some thoughts in response to a Literary Hub article on the work and its television adaptation, which has me rethinking certain ideas I had while attending college in the early 1970s.

While Butler is justifiably famous for her pioneering works of dystopian science fiction, she has pointedly observed that Kindred is not science fiction since “there’s absolutely no science in it.” Instead she calls it “grim fantasy,” which indeed is why I included it in my fantasy course. In the work, the protagonist, a black woman married to a white man, unaccountably finds herself transported back to slave times. But more on that in the essay below.

What I learned from Literary Hub article is that Kindred (according to Butler) was “a kind of reaction to some of the things going on during the 60s when people were feeling ashamed of, or more strongly, angry with their parents for not having improved things faster.” Apparently Butler didn’t like how young African Americans believed that “if they had been enslaved, they would have simply fought back harder, refusing to accept the slave masters’ punishments.” This belief, Butler worried, arose from their underestimating the severity of slavery and just how terrifying the past actually was. Therefore she

set out to write a novel that would sear that phantasmagoric violence into her readers’ psyches, a novel they could not ignore—and, more critically, could not forget. Its brutality, then, was central to its teleology, even if that made it difficult to read.

When I was attending college in the early 1970s, I remember the casual contempt that activists, White and Black alike, had for Uncle Toms. Somehow, we thought we would have been different. I now realize we were indulging in self-congratulatory illusions, which Butler’s “grim fantasy” should awaken us to. A good historical novel like Kindred alerts us to who we really are, not who we think we are.

Reprinted from September 26, 2016

I have been teaching Octavia Butler’s Kindred (1979) in my American Fantasy class and it couldn’t have come at a better time. As the body count of African Americans killed by police continues to climb, this time travel story of a modern black woman who suddenly finds herself subjected to slavery-era violence seems all too timely.

Nor is Kindred only about that. Because Dana has a white husband, the book is able to explore multiple levels of racial friction. There is no easy polarization between the races in this novel. Instead, we see how systemic racism impacts even a loving interracial marriage.

The plot goes as follows. Dana finds herself dragged back in time whenever one of her ancestors, a white slave owner named Rufus, faces death. She can return to the present only when she herself feels that she is in danger of dying. She makes six trips back in time, once with Kevin. (Anything she is touching goes with her.) While her own trips occur over a 20+ year interval, as in C. S. Lewis’s Narnia books very little time elapses in 1976 America. This means that she first encounters Rufus as a drowning child in 1815 and last leaves him when he is a plantation owner in the 1830s.

Dana, it turns out, has a blood connection with Rufus, which explains why he is able to call her back. She also knows which slave he must impregnate to start her line. If Rufus dies before giving birth to Dana’s ancestor, then presumably Dana won’t exist. (The 1985 movie Back to the Future has this plot element.)

Butler isn’t just being cute with these relationships, however. She is exploring how Black-White and also Black-Black relationships are distorted by racism. Dana therefore has mixed feelings about Rufus, whom she sees as having potential. He is even redeemed to a degree by his love for an African American woman, a relationship that is of course impossible in this society. Unfortunately, he becomes increasingly cruel as he seeks to override his empathy.

Where the story really hits home is in the relationship between Dana and her white husband. When Dana is first dragged into the past and then returns, Kevin can’t believe what she tells him about the experience. This is understandable, of course, but it is also an extreme version of how whites and blacks, even today, experience the world differently.

In fact, when Kevin accompanies Dana on one of her trips back, he sees the slave system as more benign than she does. After all, he’s dining with the master while she is witnessing slaves being whipped. Kevin may be an open-minded white man who is married to an African American woman, but we see numerous blindspots. At one point, for instance, he has romantic dreams about exploring the “Wild West” and has to be reminded by Dana that this history was less romantic for the Native Americans.

As the book continues, Dana sees unsettling similarities between Kevin and Rufus, including a desire to possess her. To Kevin’s credit, however, he spends the five years when they are separated (this in the 1820’s) working for the underground railroad and almost dying. He also deeply loves her and does all he can to get back to her. But there are things about her reality that he just can’t see.

Dana, meanwhile, has her own blindspots. For a long time, she judges one house slave severely for buying into the master’s agenda, not realizing that people must often make such compromises in order to survive. She herself is regarded with suspicion by the field slaves, and sometimes even the house slaves, for her relatively privileged position with regard to the master. Her challenge is to understand their reality. By the end of the novel, she has come closer.

One scene in particular resonated with the class. Never knowing when she will next be pulled back in time, Dana packs a kit of things that she will need to help her survive. (It is always tied to her waist so that she won’t leave it behind.) This, we said, is like African American youths going out in the world with a set of instructions in case they are stopped by the police. One never knows when one is going to be plunged into an entirely different reality.

St. Mary’s College at the moment is having an on-going series of discussions, workshops, panels, lectures, and other events to address diversity issues, so my students were particularly open to Kindred. We concluded that, like Dana and Kevin, we must have conversations that never stop.

White students (and faculty) require these conversations become they must become aware of the advantages of privilege, how we don’t need to worry about certain things. One of the best ways to become aware is to talk to students of color. The latter, very understandably, are often tired of having to educate white students about how their experiences are different. But as one African American student said to me, “It frustrates me that I always have to be the one to tell them—but then I figure that, if I don’t, they’ll never learn.”

I thanked her for her generosity and said that we all stood to gain if we work together. The Dana-Kevin marriage can survive systemic racism.

Additional posts on Octavia Butler’s Kindred

We Must Revisit Slavery to Find Healing

Learning from Butler to Grapple with White Privilege