Wednesday

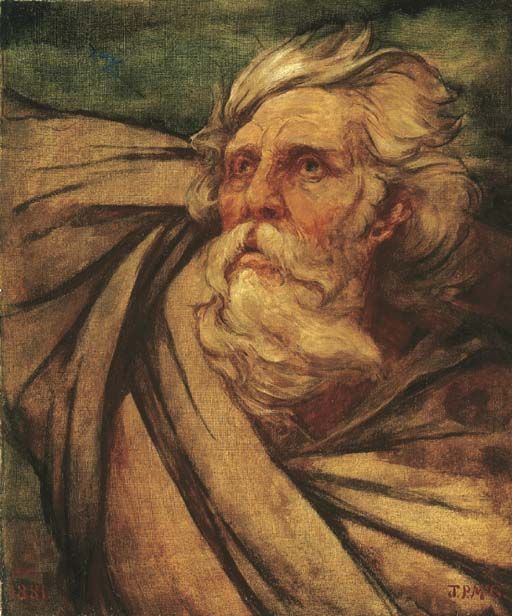

This is a follow-up to yesterday’s post comparing Donald Trump to King Lear. The more I think about it, the more disturbing the parallels appear.

To set up my further thoughts, I quote from a remarkable Rebecca Solnit article that pulls from Pushkin’s story of the golden fish, The Great Gatsby, and The Picture of Dorian Gray to capture the horror that is Trump. In her description one sees Lear as well:

Once upon a time, a child was born into wealth and wanted for nothing, but he was possessed by bottomless, endless, grating, grasping wanting, and wanted more, and got it, and more after that, and always more. He was a pair of ragged orange claws [Alert: J. Alfred Prufrock reference] upon the ocean floor, forever scuttling, pinching, reaching for more, a carrion crab, a lobster and a boiling lobster pot in one, a termite, a tyrant over his own little empires. He got a boost at the beginning from the wealth handed him and then moved among grifters and mobsters who cut him slack as long as he was useful, or maybe there’s slack in arenas where people live by personal loyalty until they betray, and not by rules, and certainly not by the law or the book. So for seven decades, he fed his appetites and exercised his license to lie, cheat, steal, and stiff working people of their wages, made messes, left them behind, grabbed more baubles, and left them in ruin.

Lear too is possessed by “bottomless, endless, grating, grasping wanting.” Shakespeare’s tragedy gives us a picture of the damage Trump could do to America while also showing what it would take for Trump to find his soul again. (For Lear it requires imprisonment and the love of an estranged daughter.)

First of all, if you have any remaining hopes that Trump can grow into the role of president—that he can become presidential—look at Lear and forget about it. Lear’s narcissism is so profound that he is willing to plunge his country into civil war to deal with his insecurities.

Underlying all of Lear’s bluster is the fear that he is insignificant. He plays his “love” game because he suddenly realizes that all the power in the world won’t save him from aging and death. He knows deep down that he needs love but, since he is used to having everything his own way, he tries to get love on his own terms (to quote from Trump’s favorite movie Citizen Kane).

What he gets instead, of course, is people telling him what he wants to hear. Then, when he no longer has power, he discovers that all their words were empty. At that point, he can no longer evade his loneliness.

Solnit explains why tyrants are invariably lonely:

I have often run across men (and rarely, but not never, women) who have become so powerful in their lives that there is no one to tell them when they are cruel, wrong, foolish, absurd, repugnant. In the end there is no one else in their world, because when you are not willing to hear how others feel, what others need, when you do not care, you are not willing to acknowledge others’ existence. That’s how it’s lonely at the top. It is as if these petty tyrants live in a world without honest mirrors, without others, without gravity, and they are buffered from the consequences of their failures…

Some use their power to silence that and live in the void of their own increasingly deteriorating, off-course sense of self and meaning. It’s like going mad on a desert island, only with sycophants and room service. It’s like having a compliant compass that agrees north is whatever you want it to be. The tyrant of a family, the tyrant of a little business or a huge enterprise, the tyrant of a nation. Power corrupts, and absolute power often corrupts the awareness of those who possess it. Or reduces it: narcissists, sociopaths, and egomaniacs are people for whom others don’t exist.

This is why Cordelia refuses to go along with Lear’s game. She knows that true love involves give and take and she won’t participate in a charade. Give and take, as Solnit points out, is also how democracy works:

We keep each other honest, we keep each other good with our feedback, our intolerance of meanness and falsehood, our demands that the people we are with listen, respect, respond—if we are allowed to, if we are free and valued ourselves. There is a democracy of social discourse, in which we are reminded that as we are beset with desires and fears and feelings, so are others; there was an old woman in Occupy Wall Street I always go back to who said, “We’re fighting for a society in which everyone is important.” That’s what a democracy of mind and heart, as well as economy and polity, would look like.

Once Lear divides his kingdom into two, civil war is inevitable, and tensions between Cornwall and Albany arise immediately. We can note that Trump too has ridden divisiveness to the presidency, and has made no attempt—as all previous presidents have done—to reach out to the other side. Incidentally, nothing terrified Shakespeare more than civil strife, which is present in practically all of his history plays and in a fair number of his tragedies. The horrors of recent history, the War of the Roses and the Catholic-Protestant clashes, loomed large in his mind.

The good news for Trump is that even Lear gets his humanity and his soul back. It takes real adversity for it to happen, however, with his darkest moment proving to be his salvation. Only when he suffers does he learn what love is.

If Lear were given a choice between all his years as king and his last day, he would choose those final moments with Cordelia. Everything else seems trivial in comparison.

It seems strange to think that impeachment or imprisonment might be the best thing that could happen to Trump, but I think it might be true. Solnit talks about the deep yearning for limits that she saw with her fellow college students who came from wealthy famlies:

The rich kids I met in college were flailing as though they wanted to find walls around them, leapt as though they wanted there to be gravity and to hit ground, even bottom, but parents and privilege kept throwing out safety nets and buffers, kept padding the walls and picking up the pieces, so that all their acts were meaningless, literally inconsequential. They floated like astronauts in outer space.

Maybe disgraced and rejected, Trump could find a genuine relationship with one of his children, laughing together at things they used to take seriously:

Come, let’s away to prison:

We two alone will sing like birds i’ the cage:

When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down,

And ask of thee forgiveness: so we’ll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we’ll talk with them too,

Who loses and who wins; who’s in, who’s out;

And take upon’s the mystery of things,

As if we were God’s spies: and we’ll wear out,

In a wall’d prison, packs and sects of great ones,

That ebb and flow by the moon.

As long as he continues to be buoyed by his enablers, however, Trump will remain in the hell of loneliness. One could feel sorry for him only, like Lear, he makes everyone around him pay for his unhappiness and, like Lear, he has the power to do a lot of damage.

Previous Posts on Trump, the GOP, and King Lear

March 30, 2017: Will Trump, Like Lear, Take Us All Down?

March 21, 2017: Trump as Lear, Howling in the Storm

March 10, 2016: #NeverTrump! Never! Never! Never! Never?

May 9, 2016: Time for GOP Moderates To Go to Ground?

May 8, 2016: Now, Gods, Stand Up for Trump!

Dec. 30, 2015: Conservative Extremists as King Lear