This post will have to be quick because it’s been a busy week. I’ve been involved in marathon grading sessions, attended a full day of senior project presentations (including one that I mentored on Hans Christian Andersen), met with multiple students who are revising essays, and have just returned from a session where students read their work from the Avatar, the college’s literary magazine.

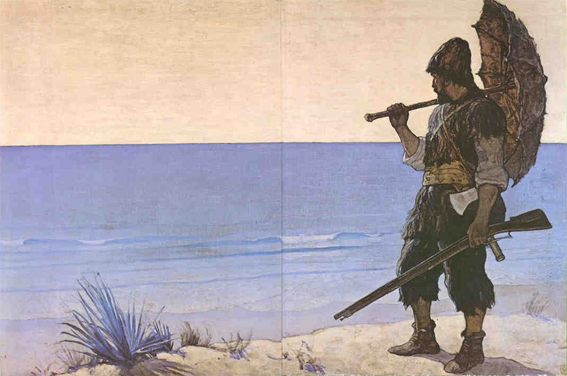

Here’s one thing I’ve noticed amidst all the swirl. Daniel Defoe’s 1719 novel Robinson Crusoe still packs a punch. A number of my Introduction to Literature students have written their essays about it. Most have chosen to write on the theme of separating from one’s father.

The father-son relationship in the book is tempestuous. The elder Crusoe wants Robinson to follow “the middle way” and become a lawyer. Being well off but not too rich is the key to happiness, he tells his son. Robinson, however, feels compelled to go to sea and breaks with his family. He never sees them again but is plagued with guilt for large sections of the book. Every time misfortune strikes, he thinks that God is punishing him for having disobeyed his father.

The story strikes a chord because many of my students have father dramas. One of them described having to argue with his parents about attending a liberal arts college because they expected him to be an engineer. Another criticized Crusoe because of his disobedience, only to reveal that her own relationship with her father has been rocky—which is to say, she idealizes the father-child relationship but lives a far different reality. (Like Crusoe she herself feels she needs to cut the strings and yet feels guilty for feeling this way.) Yet another was appalled at the way Crusoe, like the student’s own father, sacrifices people on his way to success. He picked up on an observation we made in class, that Crusoe manages to domesticate the island in impressive ways but never once talks about enjoying a sunset.

And then there was an essay by one of my African American students, who launched into Crusoe for the way that he sells his Moorish friend Xury as a slave—and only regrets what he has done when he realizes that he could use Xury’s labor. (Crusoe is on his way to Africa to purchase slaves for his Brazilian planation when he has his shipwreck.) The student noted that Crusoe’s instrumental relationship with people leads to paranoia and an inner emptiness. At the end of the book, when Crusoe returns to England, he marries but can’t settle down and must be off again.

The challenge when teaching a work is to balance subjective readings with the objective text. A book will only make an impact if it addresses an issue we care about or can come to care about. On the other hand, if we project our own issues onto a book, we may fail to hear how it is telling us something we don’t know. There is a dialogue between self and other that I watch out for in these essays. Put yourself into the book, I tell my students. Tell your own stories. And yet, you must back up any claims you make about the book with textual evidence.

Sometimes it takes an individual conference to move the students out of their projections. But that’s all well and good—it’s not easy to hear perspectives that are not your own, and these conferences are some of the most profound talks I have with students. Both they and I learn something.

My goal is for there to be something at stake in the essays they write. Usually there is. And then all the work feels worth it.

One Trackback

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by francisco santos. francisco santos said: Literature and Student Life Stories by Prof. R.Bates. Defoe’s 1719 novel Robinson Crusoe still packs a punch. http://tinyurl.com/3y4254t […]