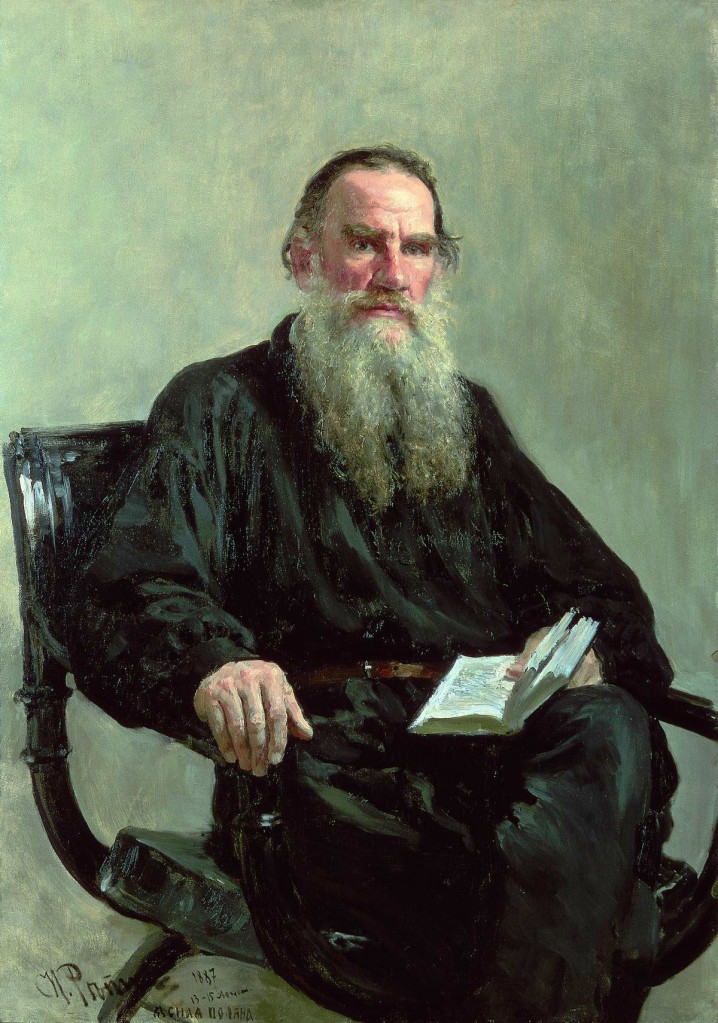

Leo Tolstoy

I’ve had a chance to revisit the two classics that immediately came to mind the other day when I thought about literary depictions of pain. Both were as powerful as I remember. In D. H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, the death of the mother goes on and on, page after page. As her son Paul says at one point,

“There are different ways of dying. My father’s people are frightened, and have to be hauled out of life into death like cattle into a slaughterhouse, pulled by the neck; but my mother’s people are pushed from behind, inch by inch. They are stubborn people, and won’t die.”

For Lawrence, life is relentless and it is insistent. It keeps coming, even when it has run its course. Mrs. Morel hangs on despite her children, in an act of mercy, administering a lethal dose of morphine:

“They sat down again helplessly. Again came the great, snoring breath. Again they hung suspended. Again it was given back, long and harsh. The sound, so irregular, at such wide intervals, sounded through the house. Morel, in his room, slept on. Paul and Annie sat crouched, huddled, motionless. The great snoring sound began again—there was a painful pause while the breath was held—back came the rasping breath. Minute after minute passed. Paul looked at her again, bending low over her.

“She may last like this,” he said.

They were both silent. He looked out of the window, and could faintly discern the snow on the garden.

“You go to my bed,” he said to Annie. “I’ll sit up.”

“No,” she said, “I’ll stop with you.”

“I’d rather you didn’t,” he said.

At last Annie crept out of the room, and he was alone. He hugged himself in his brown blanket, crouched in front of his mother, watching. She looked dreadful, with the bottom jaw fallen back. He watched. Sometimes he thought the great breath would never begin again. He could not bear it—the waiting. Then suddenly, startling him, came the great harsh sound. He mended the fire again, noiselessly. She must not be disturbed. The minutes went by. The night was going, breath by breath. Each time the sound came he felt it wring him, till at last he could not feel so much.”

Lawrence doesn’t judge Annie and Paul for their action and I don’t either. Nor do I judge the doctor who (I suspect but don’t know for sure) hastened my grandmother’s death by a few hours with a similar overdose. I suspect that physicians have in fact been doing this for centuries. Dr. Jack Kevorkian’s real crime may have been, not assisting patients with suicide, but bringing the practice out into the open and forcing governing bodies to rule on it.

Sons and Lovers should be required reading for anyone involved in euthanasia conversations. However one comes down on the issue, one should be required to take into account those who are suffering, not shield oneself from feeling by mechanistically invoking an ideological stance. Literature can help with this.

One novel that foregrounds the moral dilemma is Walter Miller’s post-apocalyptic novel Canticle for Leibowitz (1960). Special suicide centers have been set up for people suffering from terminal radiation poison, and a Catholic priest tries to argue people out of using them. He is fully aware of their terrible pain as he does so. Not all follow his advice and he understands when they don’t. But he keeps on trying.

The other work I remembered was Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilych. The pain Ilych experiences is so intense that, near the end, he screams for three straight days. Tolstoy makes the powerful point that the pain is not only physical:

“Ilych’s physical sufferings were terrible, but worse than the physical sufferings were his mental sufferings, which were his chief torture. His mental sufferings were due to the fact that that night, as he looked at Gerasim’s sleepy, good-natured face with its prominent cheek-bones, the question suddenly occurred to him: “What if my whole life has been wrong?”

In the midst of this agony, however, he suddenly achieves a new realization. For the first time in his self-absorbed life, he starts thinking and caring about others, namely the family members around him who are tied in knots over his suffering. At that moment, the physical pain becomes a secondary concern:

“And suddenly it grew clear to him that what had been oppressing him and would not leave him was all dropping away at once from two sides, from ten sides, and from all sides. He was sorry for them, he must act so as not to hurt them: release them and free himself from these sufferings. “How good and how simple!” he thought. “And the pain?” he asked himself. “What has become of it? Where are you, pain?”

He turned his attention to it.

“Yes, here it is. Well, what of it? Let the pain be.”

“And death…where is it?”

He sought his former accustomed fear of death and did not find it. “Where is it? What death?” There was no fear because there was no death.

In place of death there was light.

“So that’s what it is!” he suddenly exclaimed aloud. “What joy!”

To him all this happened in a single instant, and the meaning of that instant did not change. For those present his agony continued for another two hours. Something rattled in his throat, his emaciated body twitched, then the gasping and rattle became less and less frequent.

“It is finished!” said someone near him.

He heard these words and repeated them in his soul.

“Death is finished,” he said to himself. “It is no more!”

He drew in a breath, stopped in the midst of a sigh, stretched out, and died.

Elaine Scarry’s claims to the contrary (in The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World), language and literature can take us into the pain of another. Moreover, literature can help us see different dimensions of that pain. It won’t make the pain go away, but it sets up paths of connection between the sufferer and friends.

As I think about it, maybe the fear of suffering by oneself is part of what motivates Scarry’s book, or at least the few pages I read for our salon (see Monday’s post). Experiencing pain in solitude seems terribly unfair, and in our anger and frustration we may vent against the inadequacies of language. But language, especially literary language, is one of our greatest resources, a rope bridge thrown across a chasm. Because of such language, we are not entirely alone.