Wednesday

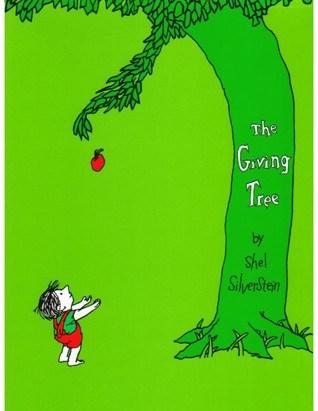

I’ve never liked Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree, where a tree takes masochistic delight in her lifelong devotion to a boy who, when he becomes a man, exploits her and ultimately reduces her to a stump. A classic enabler, she is “happy” regardless of what he does to her. Having read the story meant that I could appreciate a recent Alexandra Petri column in The Washington Post. Petri sees a version of the man in Ryan Lochte, the American gold medal swimmer who played to the hilt the role of the ugly American in the Brazil Olympics. She also applies the story to Brock Turner.

As you probably know, Lochte vandalized a gas station bathroom, which drew the attention of the police. He later claimed that he had been robbed at gunpoint, but the story fell apart fairly quickly and something resembling the truth came out. Brazil, which is fighting against Western stereotypes, was offended, and the whole affair left a stain on what was otherwise a stellar U.S. performance in this year’s games.

For his part, Turner sexually assaulted an unconscious woman but received a six month sentence because the judge felt sorry for him. Many observed that he would have received a harsher sentence had he been poor or a person of color.

Petri titles her column “Ryan Lochte and the Privilege Tree.” In her version of the parable, Lochte commits one outrage after another but is always protected by his privilege. She makes clear how, if he were black, he would not receive such a tolerant reception. Here’s a sampling. The gun incident, of course, is an allusion to Tamir Rice, the Cleveland 12-year-old who was shot by police while playing with a toy gun:

One day the boy was hungry. “Tree,” said the boy, “I am hungry.”

“I know what to do,” the tree said. “Go to the corner store and steal some candy and run back here to me.”

And the boy did. He filled his pockets with candy and ran back to the tree as quickly as he could. The man who owned the store chased after him, but when he saw the boy beneath his tree he shrugged and said, “Boys will be boys.” And there were no consequences, and the tree protected him, and the theft did not go on his permanent record. (For, after all, he was just a boy.)

The boy grew older. “Tree,” said the boy one day, “I am bored.”

“I know what to do,” the tree said. “Pluck one of my branches and carve it into a toy gun and wave it around. That will amuse you.”

And the boy did. And the tree sheltered him under its thick leafy canopy of privilege and everyone who saw him shrugged and said, “Boys will be boys.” And there were no consequences, and the tree protected him, and no one even thought to telephone the police. (For, after all, he was just a boy.)

Petri’s story concludes with the ending of white privilege, which forces Lochte to face up to consequences:

And the boy grew very old and so did the tree. One day the boy heard his tree creaking in the wind.

“What is the matter, tree?” the boy asked. “Are you all right?”

“No,” the tree said, and shivered. “I am not. Trees like me should be for children, not grown men. Look.” And the tree pointed, and the boy saw for the first time that there were not many trees like his still standing. “I ought to have been cut down long ago.”

“Cut down?” the boy asked, and for the first time in his life the boy was frightened. “But then what will happen to me if I do something wrong?”

The tree shrugged. “The same thing that happens to everyone else,” it said. And the tree groaned and fell.

And the boy saw that the world was not quite so wonderful when you could not shelter anywhere better than a Reasonable Doubt Shrub (which is nice, but nothing like a Privilege Tree). And the boy saw that it was not he who was wonderful, but his tree, which had protected him for so long, without his realizing it. And the boy, at last, grew up.

Some say.

I believe that Trumpism and the rise of the extreme right are, above all, the result of a white temper tantrum over the browning of America. Petri points out that white privilege may not be around too much longer to protect those who have long taken advantage of it.