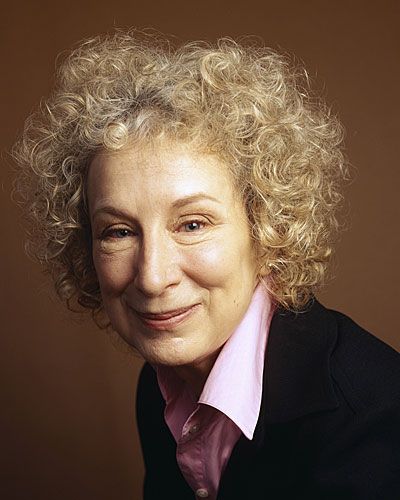

Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood’s most famous novel may be her futurist nightmare The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). In her two most recent novels, Atwood returns to the dystopian genre and paints a picture of a world in which unbridled capitalism, environmental devastation, urban decay, sexual license, runaway gene splicing, and extreme income disparity rule the earth. My book discussion group emerged from The Year of the Flood thoroughly depressed.

Last week I asked where were the literary voices that were speaking up against the irresponsible forces in our society. I should have mentioned Canada’s best known author. Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood both occur during the same time in the not-too-distant future (characters overlap between them), and both function as a wake-up call. If we aren’t vigilant—if we don’t regulate irresponsible corporations, monitor genetic engineering, and ban extreme sexuality, if we don’t protect nature and revitalize our cities and spread the wealth—then we may be visited by a second Noah’s flood. This one waterless.

Back in the 1970’s I remember reading a critique of postmodernism by Gerald Graff, at that time a member of the Northwestern English Department. Radical young academics were trumpeting deconstruction’s potential to shake up tradition and liberate women, oppressed minorities, gays, developing nations, and the like. Although Graff’s politics were liberal, he nevertheless warned us to be careful about what we sought to dismantle. Capitalism, he wrote, would like nothing better than to see old orthodoxies swept aside. After all, ultimately it opposes inhibitions because it is against anything that stands in the way of people buying things.

Atwood takes the trajectory that Graff predicted and pushes it into the future. In her two recent novels, one sees corporations doing anything and everything to make money, including the following:

–the pharmaceutical companies generate diseases in the population and then provide the cures for those diseases. Since they have exclusive rights to the cures, they make exorbitant profits.

–prisons, having become for-profit institutions, merge with reality television so that spectators get to watch inmates fight to the death in a game called “painball.”

–exotic species become expensive restaurant fare and luxury fashion items so that one after another goes extinct.

–corporations raid each other for their talent and not just metaphorically. Geniuses in one company are kidnapped by other companies.

–the elite live in gated compounds and their wives visit luxurious spas, where they delay aging through cutting edge technologies.

–there are elaborate brothels, such as “Scales and Tails,” where corporations entertain their guests. The women who work in them can don high tech bird and snake outfits as they cater to customers’ fantasies.

–the Happicuppa franchise (inspired by Starbucks) is providing everyone their favorite drink, although they must decimate the environment to grow the beans.

And so on. Writer Ursula Leguin once said that, in science fiction, the future is a metaphor for the present, and Atwood zeroes in on some disturbing tendencies in the present. Not that history will unfold in exactly this way. When one looks back at dystopias of the past, one is struck by how much more they get wrong than they get right. But LeGuin’s point is that, whatever happens tomorrow, we need to examine what is happening today.

Atwood is very good at picking up on one trend I’ve been noticing recently. Faced with, say, the prospect of dwindling oil or global warming or other disasters, some people resolutely consume more, as if, by doing so, they refute the doomsayers. To prove that global warming is a myth, for instance, they turn their air conditioning down to 68 degrees.

They follow the example of their leaders as they do this. For instance, Ronald Reagan found Jimmy Carter’s conservation efforts to be a downer and removed the solar cells that he had installed on the White House. How can it be “morning in America” if people are worried about running out of fuel? Reasoning along the same lines, Dick Cheney refused to allow any talk of conservation to appear in his energy plan.

Think about that for a moment. If America had achieved the energy independence that Carter dreamed of, the Twin Towers would probably be still standing and we would not have fought the two Iraqi wars or the Afghanistan war.

I have to say that I am not a fan of dystopian fiction, whether it be Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s Brave New World, Zamiatin’s We, Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (made into the movie Bladerunner), or others. Maybe it’s because I’m revealing my own American tendency to deny the worst so that I can remain optimistic. After all, I can crumple and withdraw when I get discouraged.

I say this as a self challenge.The proper response to a good dystopia is to leap into action.This grim literature can be a bracing tonic.It’s even more effective if it is laced with dark comedy, as Atwood’s writing often is.

In Year of the Flood, for instance, Atwood has genetics achieving the Garden of Eden vision of the lamb lying down with the lion. The creature is called a liobam and it has a way of confusing predators.

In a famous essay, Atwood once distinguished between the American and the Canadian ways of seeing the world. Americans, she said, tend to think in terms of the frontier myth. There are always new worlds to explore or to build. Canadians, by contrast, think in terms of survival. As in, “Can we make it through the winter?”

My writing group, all Americans, were not enthusiastic about Atwood’s account of people trying to survive in a devastated future world. We preferred the other Atwood works we had discussed, which were Lady Oracle, Cat’s Eye, The Robber Bride, Alias Grace, The Blind Assassin and The Penelopiad. But we had to acknowledge that Year of the Flood got us to see our world in a new light.

Which is what one hopes for from a novelist.