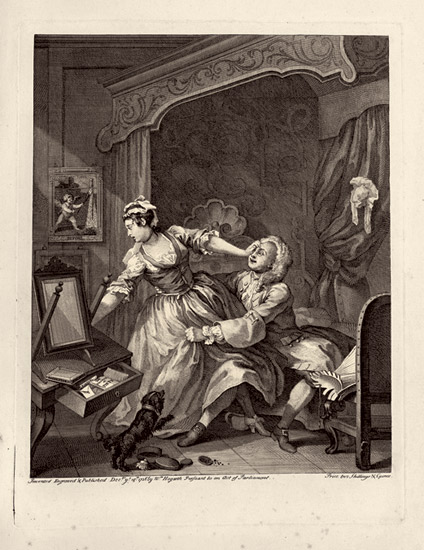

“Before,” by William Hogarth (1736)

“Before,” by William Hogarth (1736)

What can happen to your daughters if they read novels? According to William Hogarth, something like the above.

Check out the lower left hand corner where a side table is falling over. The drawer has been left casually but deliberately open so that one can see the book that is proudly displayed there: The Practice of Piety. (This can be seen easily in larger versions of the print.) The book on top of the table, meanwhile, may be Discourse concerning Baptismal and Spiritual Regeneration by the Bishop of Rochester (it just says “Rochester”).

But if one looks further into the drawer, there is another book hidden away, labeled “novel.” The young woman in the picture only seems to be resisting the man’s advances. In reality, she has already been corrupted.

In other words, it is not only Samuel Johnson (see yesterday’s post) who associates novels with scandalous behavior.

Richard Sheridan, in his delightful School for Scandal (George Washington’s favorite play), makes fun of the suspicion of novels when the heroine must quickly make her apartment respectable for unexpected company. Here she is talking to her maid:

“Here, my dear Lucy, hide these books – Quick, quick – Fling Peregrine Pickle under the toilet—throw Roderick Random into the closet – put The Innocent Adultery into The Whole Duty of Man – thrust Lord Aimworth under the sofa –- cram Ovid behind the bolster – there – put The Man of Feeling into your pocket – so, so, now lay Mrs Chapone in sight, and leave Fordyce’s Sermons open on the table. O burn it, the hairdresser has torn away as far as Proper Pride [to use for hair curlers]. Never mind—open at Sobriety,–fling me Lord Chesterfield’s Letters,–Now for ‘em.

On the scandalous side, Roderick Random and Peregrine Pickles are rowdy novels by Tobias Smollett (my dissertation subject), Man of Feeling is a tearjerker by William McKenzie, and Ovid is the Roman author of The Art of Love. I’m not sure about Lord Aimworth or The Art of Adultery but the latter speaks for itself.

On the respectable, Whole Duty of Man was a 1658 devotional text and Fordyce’s Sermons are the preferred reading of Mr. Collins in Pride and Prejudice (enough said on that score). Hester Chapone wrote Letters on the Improvement of the Mind, Addressed to a Young Lady while Lord Chesterfield’s Letters to his Son are elegantly penned advice. Parents of the age regularly pushed such reading towards their children.

Normally I am a great fan of Samuel Johnson, who takes reading as seriously as anyone ever has. But I think his Rambler essay #4 is wrong in its anxieties about young people reading novels. I also find it interesting that, in that essay, he only finds harmful the stories that contemporary young people were reading, not the reading he himself engaged in while young.

This older fiction included romances, about which Johnson writes the following:

“In the romances formerly written, every transaction and sentiment was so remote from all that passes among men, that the reader was in very little danger of making any applications to himself; the virtues and crimes were equally beyond his sphere of activity; and he amused himself with heroes and with traitors, deliverers and persecutors, as with beings of another species, whose actions were regulated upon motives of their own, and who had neither faults nor excellencies in common with himself.”

Johnson has in mind stories about kidnapped ladies and the knights that ride in to save them, stories with hermits and battles and shipwrecks. In other words, he sees the new novelistic emphasis on everyday reality as the real danger.

And yet, in Cervantes’ Don Quixote we have the account of a man whose head is turned by magical romances. Just because a story involves magic and faraway times doesn’t mean that it can’t seize the mind. Witness Harry Potter, both its popularity and the consternation it is causing amongst certain fundamentalist Christians.

Stories of one’s youth always seem benign. Johnson was born in 1709, and the novel didn’t really start to take off until Samuel Richardson’s Pamela in 1742. Johnson’s objections sound suspiciously like an adult complaining about the books read by the next generation while giving his own a pass.

A far healthier response to youthful reading is that of Jane Austen in Northanger Abbey. In Friday’s post I quoted the passage where she identifies the stigma against novels. She seems to be echoing School for Scandal when she notes that a young woman would rather be “caught” reading the polished and elegant essays from The Spectator, written by Addison and Steele a century earlier, than a novel. She also points out that parents and other moralists will give more praise to a warmed over History of England or to someone who compiles a tiresome collection of poems and writings by writers from the past than someone who writes an original work of fiction

Austen seems to take the side of young people as she notes how novels fire their blood. To be sure, she also teases them when she overpraises novels: “Some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humor, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.” It’s as though she’s parodying youthful enthusiasm. But ultimately, she conveys that everyone is overreacting. Lighten up people, I imagine her saying.

Her own novel then goes on to show a much more balanced approach to teenage reading. I’ll explore the case she makes tomorrow, but basically I see her demonstrating that, if children have been raised right, they will be able to come to their own mature assessment of novels.

If you are the anxious parent of a teen, I heartily recommend Northanger Abbey. It may reassure you.

One Trackback

[…] Mocking Adult Anxieties About Novels […]