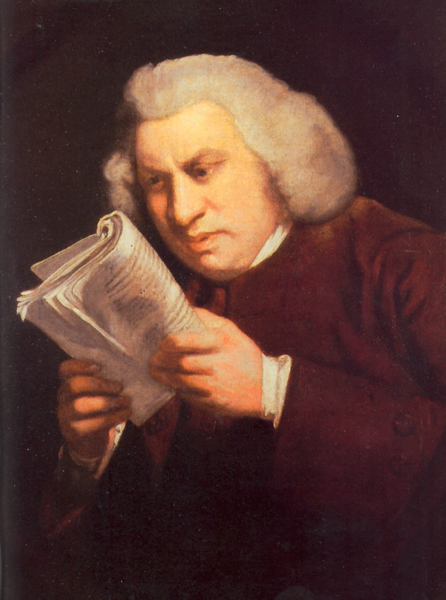

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

If we need proof that adolescence has always been a difficult age, we can look at those 18th century moralists that were panicked about young people reading novels.

Of course if you’re young (to build off of a comment that Barbara makes in response to Friday’s post), part of the fun of reading novels is panicking one’s parents.

One panicked adult was Samuel Johnson, England’s greatest critic. His 1750 Rambler essay #4, which focuses on novel reading, reveals his fears about young people being improperly influenced. The novels today, he complains, are being written chiefly to:

“the young, the ignorant, and the idle, to whom they serve as lectures of conduct, and introductions into life. They are the entertainment of minds unfurnished with ideas, and therefore easily susceptible of impressions; not fixed by principles, and therefore easily following the current of fancy; not informed by experience, and consequently open to every false suggestion and partial account.”

Young people, Johnson says, need to be protected:

“That the highest degree of reverence should be paid to youth, and that nothing indecent should be suffered to approach their eyes or ears, are precepts extorted by sense and virtue from an ancient writer [the Roman writer Horace], by no means eminent for chastity of thought. The same kind, though not the same degree, of caution, is required in everything which is laid before them, to secure them from unjust prejudices, perverse opinions, and incongruous combinations of images.”

So what does Johnson find so dangerous about novels?

“But when an adventurer is leveled with the rest of the world, and acts in such scenes of the universal drama, as may be the lot of any other man; young spectators fix their eyes upon him with closer attention, and hope, by observing his behavior and success, to regulate their own practices, when they shall be engaged in the like part.”

I like the way that Johnson goes on to describe the power of novels, which captures my own sense of their ability to immerse us in their worlds. He says that “the power of example is so great”—he’s talking about the hold that a character may have on us—that it is as though the novel takes possession of our memory “by a kind of violence, and produce[s] effects almost without the intervention of the will.”

These are the words of a man who knows what it is like to be in the grip of a novel.

Because novels have this power, Johnson warns us that they must be regulated. We should allow only those novels that show behavior that we want our young people to emulate. Novels that show other behavior are likely to have “mischievous” effects.

These effects include lessening our aversion to vice. Johnson has in mind novels such as Tom Jones when he pens the following:

“Many writers, for the sake of following nature, so mingle good and bad qualities in their principal personages, that they are both equally conspicuous; and as we accompany them through their adventures with delight, and are led by degrees to interest ourselves in their favour, we lose the abhorrence of their faults, because they do not hinder our pleasure, or, perhaps, regard them with some kindness, for being united with so much merit.”

Tom Jones was very popular with young people in the 18th century and was also my favorite novel when I was in my early 20’s. One can understand why. Although Tom is full of animal spirits (or youthful hormones) and is always getting into trouble, we forgive him because he has a good heart. Meanwhile Sophia, albeit a dutiful daughter, is shown being plagued by her sanctimonious aunt and forced into a loveless marriage by her tyrannical father. The parental figures in these books are basically clueless, and the children have to learn how to negotiate the newly urbanized England on their own.

In the end, they get their “happily ever after.” In a young person’s wish fulfillment, Squire Allworthy must admit to Tom that he was wrong about him, and Squire Western comes around to acknowledging that Sophia’s choice of Tom for a husband is best. (Excuse the spoiler, but the reader knows from early on that Tom and Sophia will end up together.)

Here’s what Johnson thought of Fielding and Fielding’s book, according to Boswell’s Life of Johnson:

“Fielding being mentioned, Johnson exclaimed, “he was a blockhead.” . . . “What I mean by his being a blockhead is that he was a barren rascal.” BOSWELL. “Will you not allow, Sir, that he draws very natural pictures of human life?” JOHNSON. “Why, Sir, it is of very low life. Richardson used to say, that had he not known who Fielding was, he should have believed he was an ostler. Sir, there is more knowledge of the heart in one letter of Richardson’s, than in all Tom Jones.” (Life, II, 173-174)

To apply the Rambler essay to Tom Jones, Johnson was worried that young men would “lose the abhorrence” of Tom’s faults, or “regard them with some kindness, for being united with so much merit.” And although we sometimes wish that young people today would read more novels, not fewer, the anxieties about young people continues on.

Why else do school systems still ban Catcher in the Rye or Are You There God, It’s Me Margaret? Look at the adult anxieties involved in the incident I’ve mentioned a number of times, Superintendent Pat Richardson of St. Mary’s County (Maryland) forbidding English teachers to teach Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, even though it was on the Advanced Placement list of recommended books. The three pages that caused the commotion, I’m pretty sure, are ones describing trash talking between the protagonist Milkman and a North Carolina man who is challenging him.

This kind of trash-talking occurs, continually and non-stop, on playgrounds and basketball courts all over America—not because boys have read Toni Morrison but because this is what boys do. We can blame books, but that is like blaming the barometer for the weather. It’s as though adults, feeling unable to control their adolescent children, find a scapegoat in books.

Maybe it would comfort them to know that people were complaining the same way in the 18th century, just as parents complained about movies in the early 1900’s and comic books in the 1930’s and television in the 1950’s and Mad Magazine in the 1960’s and Dungeons and Dragons in the 1970’s and the internet and videogames today. Times may change but parental anxieties always seem the same. More on this subject tomorrow.

2 Trackbacks

[…] teaching in my 18th Century Couples Comedy class. I’ve mentioned in a past post that moralist Samuel Johnson attacked Tom Jones for corrupting young people. Furthermore, the Bishop of London accused it (along with […]

[…] so threatening to many in the 18th century, an issue I have written on several times (for instance, here). When we read, we instinctively identify with the protagonist, and when (as in the case of, say, […]