Wednesday

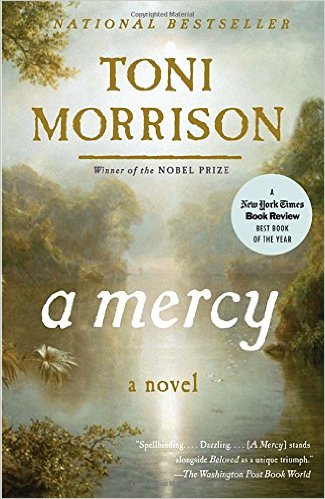

In recent months I’ve been on a Toni Morrison binge—I’ve now read everything except for Jazz and God Help the Child—and I never cease to be amazed at how timely her fiction is. In A Mercy (2008) Morrison takes a trip back into America’s origins to understand our race, ethnic and class conflicts. The novel is set in late 17th century Maryland, Virginia and New York, and we see both the promise of America and what will go wrong.

Morrison concludes that race and class prejudices will overwhelm even good faith efforts to get along. The novel was written in 2008 but it reads more as though it were written in 2016. Or rather, it seems to reflect the hope and change of the Obama 2008 campaign and then to predict Trump’s rightwing backlash.

Jacob Vaark is a New York farmer and trader who sets up a humane establishment. Included in his farm community are his wife Rebekka, rescued from a life of horror in London; an Indian slave (Messalina, a.k.a. Lina); a black slave (Florens); a multiracial slave rescued from a shipwreck (Sorrow); and two indentured—essentially enslaved—white servants (Willard and Scully). Despite the slavery, Jacob is a humane man who thinks he can buck his society and treat these people as individuals. This means keeping his bigoted Anabaptist neighbors at arm’s length and also looking down upon the extravagance of a man who owes him money, a Portuguese aristocrat who strives to recreate a European-style class system in Catholic Maryland. In other words, Jacob is a liberal facing pressure from Christian fundamentalists and sparring with Establishment types.

In the 17th century, no one knew how America would turn out. I can’t sum up Morrison’s vision of the new world better than John Updike does in his New Yorker review:

A Mercy takes us deeper into the bygone than any of Morrison’s previous novels, into a Southern seaboard still up for grabs: “1682 and Virginia was still a mess.” Indian tribes haunt the endless forest; the colonial claims of the Swedes and the Dutch have been recently repelled, and “from one year to another any stretch might be claimed by a church, controlled by a Company or become the private property of a royal’s gift to a son or a favorite.” Jacob Vaark, coming from England to take possession of a hundred and twenty acres bequeathed to him by an uncle he never met, rides from Chesapeake Bay into “Mary’s land which, at the moment, belonged to the king. Entirely.” The advantage of this private ownership is that the province allows trade with foreign markets, and Vaark is more trader than farmer at heart. The disadvantage is that “the palatinate was Romish to the core. Priests strode openly in its towns; their temples menaced its squares; their sinister missions cropped up at the edge of native villages.” His claim lies in Protestant Virginia, “seven miles from a hamlet founded by Separatists” who “had bolted from their brethren over the question of the Chosen versus the universal nature of salvation.”

Morrison’s project reminds me of Wayne Karlin’s 1998 novel Wished For Country (written about here), in which 17th century settlers, as well as indentured servants and slaves, project their desires onto a very violent new world. Both Karlin and Morrison have come up with versions of America’s heart of darkness.

For a while, however, Jacob’s arrangement works. Messalina develops a close friendship with her mistress and also with African American Florens. The two white indentured servants get along well with the people of color and also develop a homosexual relationship. Jacobs, meanwhile, becomes a slave owner almost by accident: the women have been cast off by people less tolerant or, in Florens’s case, sold to him to pay off a debt (he accepts her only to console his wife for the loss of a child). Jacob allows Lina, the one survivor from a disease-stricken Indian village, to practice various tribal customs (such as sleeping in a hammock). His wife Rebekka, meanwhile, turns away from the Anabaptists because of how they consign her unbaptized children to hell. It appears that the Vaark household will be able to escape dogma and oppression.

One of the novel’s most beautiful passages describes Rebekka’s love of the new world, a scene that reminds me of the community picnic in Beloved. The new country seems to offer a chance to begin anew:

The absence of city and shipboard stench rocked her into a kind of drunkenness that it took years to sober up from and take sweet air for granted. Rain itself became a brand-new thing: clean, sootless water falling from the sky. She clasped her hands under her chin gazing at trees taller than a cathedral, wood for warmth so plentiful it made her laugh, then weep, for her brothers and the children freezing in the city she had left behind. She had never seen birds like these, or tasted fresh water that ran over visible white stones. There was adventure in learning to cook game she’d never heard of and acquiring a taste for roast swan.

Sadly, it cannot last, and the corruption seems to stem from the moment Jacob starts yearning for the style of life lived by the Portuguese aristocrat. In modern terms, he wants to become part of the Establishment. Jacob begins speculating in the Barbados slave-sugar-rum trade (known as the triangle trade) and uses the considerable profits to build an extravagant house. America’s original sin, Morrison suggests, is greed for wealth and the means used to get it:

Killing trees in that number, without asking their permission, of course his efforts would stir up malfortune. Sure enough, when the house was close to completion he fell sick with nothing else on his mind.

Jacob dies and Rebekka almost does. When she recovers, attempting to find some meaning in a life that has gone off the rails, she turns to the Anabaptists. From a promising multicultural project, the farm falls into rigidity. Here is Florens reporting on what happens:

Mistress has cure but she is not well. Her heart is infidel. All smiles are gone. Each time she returns from the meetinghouse her eyes are nowhere and have no inside…Mistress’ eyes only look out and what she is seeing is not to her liking. Her dress is dark and quiet. She prays much. She makes us all, Lina, Sorrow, Sorrow’s daughter and me, no matter the weather, sleep either in the cowshed or the storeroom where bricks rope tools all manner of building waste are. Outside sleeping is for savages she says, so no more hammocks under trees for Lina and me even in fine weather…She does not know I am here [in the house] every night else she will whip me too as she believes her piety demands. Her churchgoing alters her but I don’t believe they tell her to behave that way. These rules are her own and she is not the same. Scully and Willard say she is putting me up for sale. But not Lina…Worse is how Mistress is to Lina. She requires her company on the way to church but sits her by the road in all weather because she cannot enter. Lina can no longer bathe in the river and must cultivate alone. I am never hearing how they once talk and laugh together while tending garden.

Morrison’s fiction seems to have gotten darker since the inspiring Song of Solomon, Obama’s favorite novel. At the moment I’m having difficulty disagreeing with her pessimism about a polarized America.